The Making of The Entire City

John Menick

May 22, 2017

It is easy to forget that Hollywood once lacked a precise understanding of the human mind. Until recently, it would have been absurd to imagine a producer, perhaps poolside in Bel Air, asking fundamental questions about human cognition, desire, need, and imagination. Instead of science, Hollywood built its empire on superstition; and superstition, as psychologists tell us, is itself built on fear. But what did Hollywood fear? In a word, the audience.

Ever since the Lumière workers left the factory, film audiences have been inscrutable, their desires prone to whims and sudden reversals. Why did audiences see last summer’s blockbuster, but not its sequel? When did our star fall from favor? How did a formula, profitable for so long, become a recipe for bankruptcy? No one knew the answers, not really, and those who claimed to know had their egos quickly demolished by the fickle public.

Without certainty, without science, survival was trial and error; the few successes Hollywood enjoyed owed more to luck than mastery. What outlived box office selection was later codified in film schools, with tenured gurus defending the faith against apostasy. To read a screenwriting manual today is to browse a work of medieval scholasticism, entire systems tottering on false belief, cruel and puzzling rituals meant to protect against cruel and puzzling ticket holders. If it had not been for The Entire City (2027), if filmmaking were still left to artists and craftspeople and studio actuaries, it is almost certain that Hollywood would have disappeared.

As we know, it did not. Hollywood outlived two bankruptcies and proved all prognosticators wrong. It emerged as one of the most profitable industries in the world, second only to pharmaceuticals. The pairing of these two industries at the top of the market is not coincidental. As told in Thomas Sinclair’s documentary, The Making of The Entire City (2029), a single scientist was responsible for both industries’ successes. Sinclair’s film has many interviewees, but Dr. Anish Mehta, Stanford University Professor of Computational Psychology, is the film’s unassuming center. It is a film made in the old style—none of Dr. Mehta’s techniques contributed to the documentary’s making—but despite its antique methodology, The Making of The Entire City is a reminder of what cinema could achieve, no matter how primitive its tools.

The Making of The Entire City begins with the demolishment of studio backlots, the collapsing facades and urban rubble resembling the apocalypses Hollywood has peddled for decades. The scene, though, is not from the 2023 Warner Bros. bankruptcy, but MGM Studio’s 1960s implosion. The analogies between the two collapses, as Sinclair points out, are numerous: new media—television and the Internet—crippled both industries, as did a change in audience tastes brought about by social revolutions. Some predicted Warner Bros.’ 2030 demise would begin a revival of films made by young directors responding directly to the American experience, but no Easy Rider (1969) appeared.

In Sinclair’s opinion, decades of superhero films and stale properties discouraged young potential auteurs away from the film industry toward the more popular and financially lucrative gaming industry. Then, in 2024, after Warner Bros.’ liquidation, Universal Studios collapsed. The President announced there would be no federal bailout of Hollywood. Americans had voted with their feet: Hollywood would be euthanized.

Enter Dr. Mehta, who, as seen in The Making of The Entire City, is an unlikely candidate for Hollywood’s savior. During his first appearance on screen—elderly, spectacled, with two storm clouds of eyebrow hair—the affable scientist confesses that he hadn’t entered a movie theater since college. His tastes, he adds, tend more towards twentieth-century Modernist literature and Baroque keyboard music. For Dr. Mehta, Hollywood’s failure was a scientific problem no different than those he solved in the lab. While working at the university and consulting for the pharmaceutical industry, Dr. Mehta developed a neural network capable of imitating not just the brain’s byzantine neuronal structure, but also its complex neurochemistry. Dr. Mehta had originally developed the system for testing today’s new customizable SSRIs; however, during his sabbatical from Stanford, he thought that his system could be repurposed to help Hollywood.

“The first step,” he tells Sinclair, “was to approach the studios for access to their back catalogs.” By training his system with thousands of titles, audience demographics, box office figures, algorithmic analysis of images, and his own research in neuroscience, Dr. Mehta created what he calls “a computational model of a filmgoer’s neurology.” Give him two years, he said to Warner Bros.’ creditors, and his system could restore Hollywood’s financial solvency. When Sinclair asks the scientist why Hollywood listened to his extravagant claims, Dr. Mehta responds with typical geniality: “Desperation.”

The result was The Entire City, now credited with not only reviving the film industry, but also changing the history of narrative art. The Entire City, like many classic films, was almost not produced. Warner studio chief Kelly Spasser: “I laughed at [the screenplay]. What was this thing? It was five sections, over 6,000 pages in total, with no narrative. It had all these random photos, and, well—I didn’t read it. None of us did.”

But Dr. Mehta and his colleagues, during several meticulous presentations, proved that the science was solid. It is true, Dr. Mehta said, that this film would resemble no other. At times the narrative was little more than a collection of vignettes. However, if Warner Bros.’ creditors obeyed every instruction, Dr. Mehta said, if they considered this screenplay a product of the latest advances in neuroscience, the studio would produce a much-needed hit. On that day, neurocinema was born.

“Like all revolutions, I guess, it was impossible to know how irrevocably the cultural was about to change,” a humble Dr. Mehta tells the camera. The proposed budget for the film, minus marketing, was $1.1 billion. Industrial Light & Magic was immediately consulted, as were three top-grossing directors. ILM, nearly bankrupt, agreed to participate. All three directors declined. Eventually, a sitcom journeyman director, Caleb Allen, was contracted to direct. (“Honestly, I just followed the script,” Allen shrugs.)

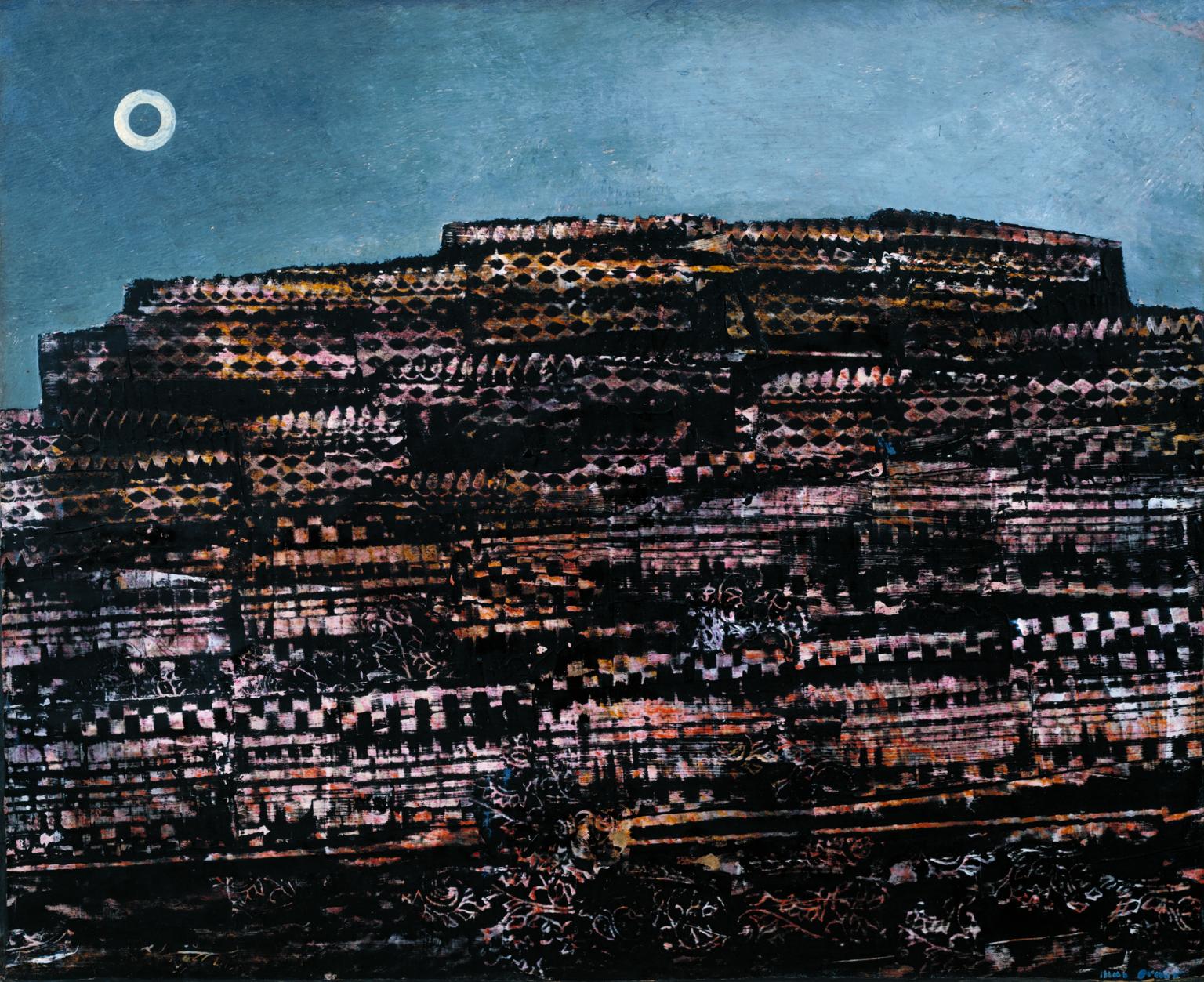

One problem remained, however. Dr. Mehta’s system did not provide a title for the film, and the screenplay’s intricate structure did not easily suggest one, either. Dr. Mehta tells Sinclair that he looked to his favorite painter, Max Ernst, for an answer. The film would take the title of the German surrealist’s twelve-painting series, La Ville entière. “There was really no good reason,” he says. “Sometimes, you need to be arbitrary.”

It is impossible to accurately describe a neurocinematic film like The Entire City to a viewer used to classical narratives such as Citizen Kane (1941) or E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982). For the few readers who have not seen it, a general overview follows. Running over five hours long, the film begins with an amalgamation of various animated and live action theatrical scenes mixed with competitive athletic events, most of which are incomplete and fragmentary. The second hour of the film consists of architectural details—doorknobs, mullions, masonry, tiling, cornices, jambs, spandrels, latticework, trusses—punctuated by the occasional window looking onto the Northern English countryside.

After an intermission, hours three and four constitute the first example of what some now call “Neuro-Opera”: a multicolored display of light and sound whose phenomenology moves audiences to emotional extremes. The Entire City concludes, inexplicably, with scenes of infancy and domesticity, which, on paper, sound as dull as a stranger’s childhood photos. Linguistic description of the scenes is irrelevant, though. It was not so much the subject matter of The Entire City that worked on audiences, but the film’s gestalt of lighting, sound, music, the revelation of space, the feeling of confinement alternating with escape.

Most people today can remember the film’s reception. Tickets priced at triple the current rate sold out for four weeks straight. Against all expert advice, audiences claimed the movie was exactly the right length. And despite the film’s unprecedented pleasure, audiences were left satisfied for days afterward, without any signs of withdrawal or craving. Only after a month or two, did they feel a need to return to theaters; but, when they returned, they enjoyed the films’ many pleasures again without diminishment. New, improvised theaters were constructed in order to keep up with the demand.

As usual, fan groups emerged, with amateur neuroscientists conjecturing as to why The Entire City affected them so deeply. There were debates as to how exactly the film calibrated our dopamine, how it pulsed adrenaline, flooded our serotonin; however, as with the first primitive SSRIs, the exact chemical workings are still unknown. Soon, traditional film criticism, already an endangered profession, was declared dead. As neuroscientist Dr. Alice Skolimowski tells us: “It was a perfect serotonergic cinema. Dr. Mehta’s research into customizable SSRIs had paid off—twice.”

A growing critical voice regarding neurocinema has emerged, contrary to expectations. Sinclair devotes perhaps too much time to the critics, all of who are involved in classical styles of filmmaking. Often labeled “neurophobic,” these critics argue that films are best made in the traditional manner. At their most extreme, the critics are scared that, given the rise of Fabula Inc., artists will become obsolete, perhaps even diminishing humanity in the process. “All they do is listen to that goddamn computer,” says film director Lilly Lee. “Sure, the movies look great, feel great,” she continued. “They have all the psychological ups and downs. But it’s not art. Art needs to surprise. Art needs to be critical of power.”

Today, Fabula Inc.’s headquarters occupies the backlot that once belonged to Warner Bros. The building complex houses the largest neural network in the world, requiring enough employees to inhabit a small American town. Thousands of engineers, computer scientists, linguists, literary historians, film historians, secretaries, interns, executives, copywriters, electricians, cleaning staff, students, and physicists tend to the network daily, their labors chronicled in two industry journals and frequent news articles.

Fabula Inc.’s research changed culture more than all the bohemian enclaves of the 20th century combined. Pace Aristotle, the company’s work shows that audiences do not seek catharsis. Audiences seek dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, epinephrine, and at least a dozen other chemicals. Neuroscience provided a shortcut around the intricacies of plotting, the difficulties of mimesis, the need for a square jaw and a beautiful damsel. As Sinclair illustrates in clip after clip, after The Entire City, Hollywood realized that its blockbusters—already short on story and long on spectacle—should have been made with even less narrative structure.

Without story, actors no longer needed the method; and, very quickly, films no longer needed actors. Film historian Claire Todd: “It was a historical irony that Hollywood came to imitate the American avant-garde. If only [American experimental filmmaker] Stan Brakhage were alive to see it.” The roles were now reversed: Hollywood cinema became more abstract, often dabbling in the surreal, and the art house became more conservative, transformed into a museum for linear stories dominated by plot and character.

Sinclair’s concluding voice-over is his documentary’s only misstep. Over a montage of forgotten B-movies, he engages in some easy nostalgia for a time, recently gone, when a film might disappoint an audience. “What have we lost,” Sinclair asks, “when we are no longer disappointed or bored? How will we understand the long narrative arcs of our lives if films themselves no longer have these arcs? How can we be the stars of our own dramas, if films no longer have dramas or stars?”

One can reply that audiences have made a clear choice. Look at the box office: global audiences have opted for Dr. Mehta’s neurocinema. Boredom, once paradoxically linked to both creativity and intellectual stagnation, is no longer worth the risk. But even if Sinclair may indulge in unwarranted sentimentality, there is one thing we can all agree on: the dark age of cinematic psychodrama has come to an end.