A 12-Step Program for “Collectors”

Bob Nickas

June 5, 2017

Once upon a time, not so long ago, there were three primary reasons why art would come back on the market, either returning to the gallery from which it had originally been sold, or brought to auction: the death of a collector, the divorce of a couple, or a precipitous decline in the source of one’s livelihood. Something had to go under: a person, a marriage, a business.

Today, however, artworks are resold for any number of reasons. The artist may be perceived as out of fashion, a name no longer poised on so many lips, bouncing from ear to ear. Collectors become bored. The ever-revolving door on a storage facility, even unseen, offers a source of amusement. Spinning it from afar gives those who don’t actually work something to do. Those who only invest, rather than collect, conflate the art market with the stock market, compelled to buy and sell to play the game, to see how an artwork will perform. Perhaps most hideously of all, too many sell because their sole means of funding further purchases is to monetize works whose value has gone up over time. And if it hasn’t, they will at least be able to turn an artwork back into cash: liquidation and liquidity commingle.

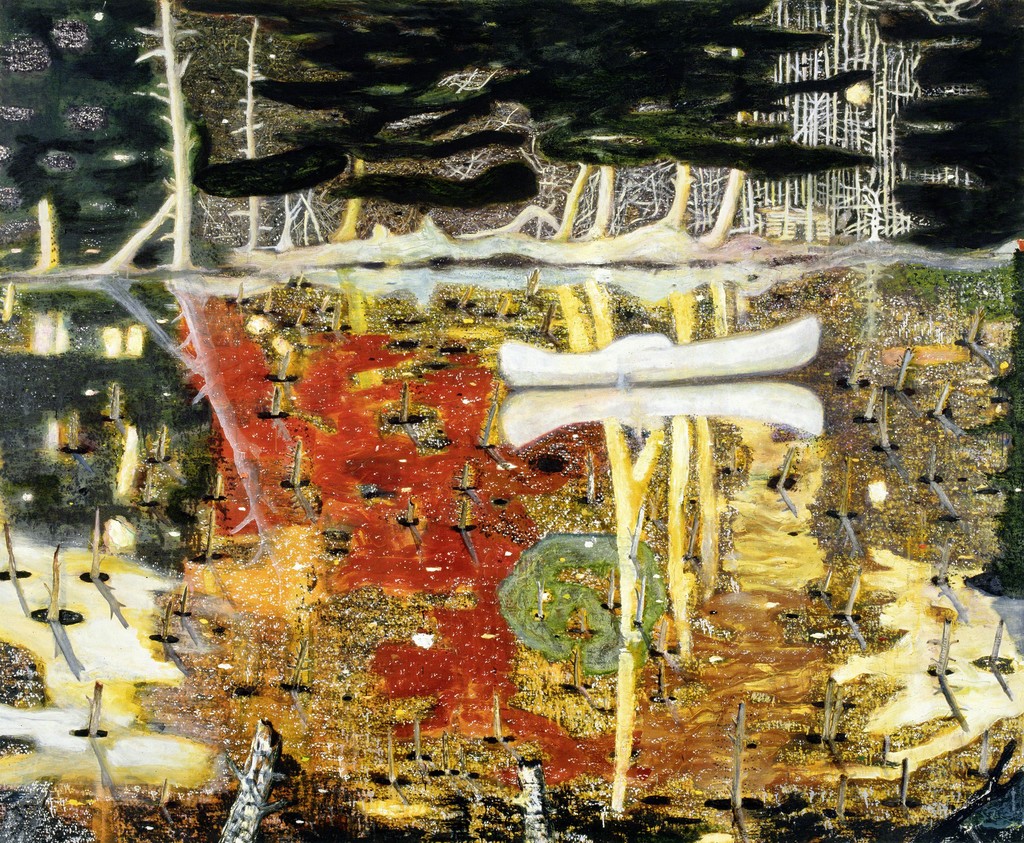

In either case, these “collectors,” in scare quotes, are not actually buying the art. The art is buying the art. The art that was cashed in, let’s say a Peter Doig painting, is used to subsequently acquire a number of works by other artists. The collectors who sold his painting purchased those other works, but Peter Doig paid for them, and he may not even admire them. The artist is the bank, for all intents and purposes, offering an interest-free loan. Never to be repaid.

As the fortunes of artists rise and fall, and they certainly earn no percentage on the resale of their work, who ends up paying the price? Collectors have not actually dug into their own pockets for the money to buy “the next new thing”—their hope, no doubt, the next Peter Doig—and neither have they gone out and earned those funds. (The source of wealth for many major collectors? Inheritance.) It’s not the art acquired that is appreciated, rather, the art itself must appreciate—to be of future use, at a point in time only rarely deferred.

The time elapsed between an initial purchase and resale increasingly constricts upon itself. Page through auction catalogs for contemporary art today; you encounter many works dated from a year or two prior to the sale, even from the same year in which the auction is taking place. Even works at auction that are older may be have been bought recently, and with the express purpose of resale. The primary and secondary markets share an elevator that supposedly only goes upwards. In all this we would be foolish to lose sight of the fact that, as Flannery O’Connor reminds us: Everything That Rises Must Converge.

How present is the primary market and who primes its pump? On a recent visit to the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, moving in between the art and the adjacent wall labels, it was clear that, with the exception of historical works, most of the art on view had been made within the prior six to eighteen months. Although there were no paintings to be seen among them, we can say of the art: “the paint had yet to dry.” The museum can assert that it aims to show what is new, what is contemporary, and in this sense, mission accomplished. Even so, it’s difficult to shake the feeling that most of what is exhibited is also for sale. This is not part of the mission statement.

Those wall labels inevitably identify one, two, or sometimes three galleries by which the works are “courtesy of,” and thus from whom they may be acquired by collectors, some of whom will inevitably turn out to be museum trustees. Supporting galleries should be acknowledged because they very often fund the production of the art, contribute to the staging of the show, possibly to the publishing of a catalog, and so on. These galleries have made an investment upon which there is meant to be a return. The danger in this is for a museum to be seen to function as an extension of a commercial gallery, or their booths at art fairs, where collectors usually go to shop. But do they shop at museums? (Haven’t they always?) And if collectors sell art within a year or two of the purchase, are they really collectors at all?

To collect is to draw things towards ourselves over time, to study and learn from them, to see what they elicit, one from another, not to engage in a continuous and expedient dispersal. One of the past exhibitions at the New Museum that resonates still, The Keeper, presented in the summer of 2016, focused on the activities of collecting, the archive, and preservation, and in that resonance is a lesson: to collect is to keep. A true collection, assembled piece-by-piece, its identity formed as each object amplifies the others (an additive rather than subtractive process) allows those by whom it has been assembled to better understand both the works and the world, and maybe even themselves. Artworks are not simply things in the world; they are devices for seeing the world anew, from various lines of sight and mind. Those who buy and sell art in the guise of collectors—what self-knowledge is gained from this behavior? (Assuming, of course, that they are reflective in some measurable way.)

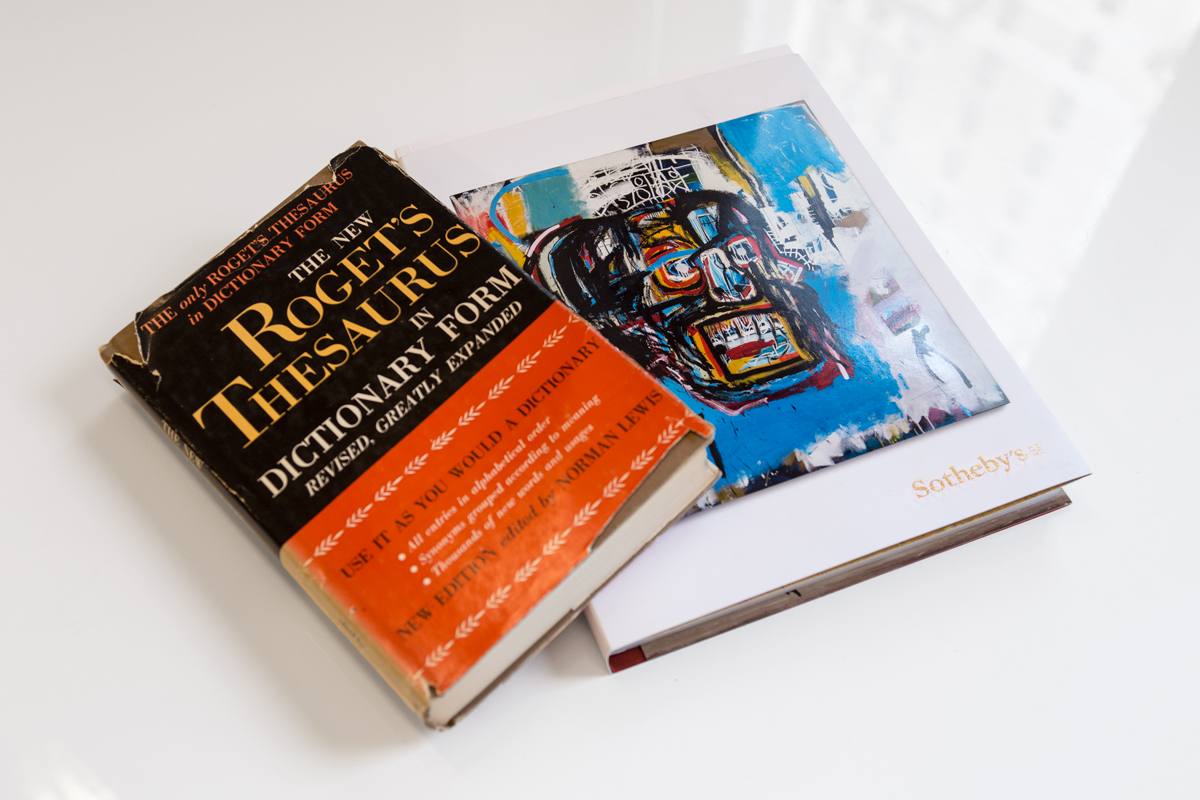

In a time when few really know what’s going on, when there’s no clear direction in art, and may never be again, the collector, who also embodies the conservator of his or her own museum, will profit from observing a full constellation of artworks, not only a handful of stars. After all, is the night sky of art only illuminated by the brightest? Are collectors more readily dazzled by shooting stars? By a “big bang?” The most recent and loudest of all: a 1982 painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat held privately for more than thirty years, sold only after, and long after, the deaths of its original owners.

Prior to being placed on the auction block the trumpets were already blaring: Basquiat may fetch $60 million at Sotheby’s. (To fetch: to go after, retrieve, as with a pet, often at another’s command.) The result: $110.5 million, a figure described as mind-blowing, the highest price ever paid for an American artist at auction. What is truly mind-blowing, however, and don’t tell its new owner, is that so much money has been spent on a work that may not be among Basquiat’s very best. Although it’s true that the image of a large gnarly skull does, by default, serve as a posthumous romanticized portrait, its iconicity borders on routine, the rendering blunt: alongside paintings created around the same period it is in no way as complex, lacking a visceral poetics.

Where is the writing, the drawing and collage, the heightened acts of inscription and invention we associate with this artist? This is a work for which Basquiat never devised a title, and while not all of his paintings are titled, language is central to his voice and its articulation, to amplify pictorial volume, and in which he was well versed. No matter. Could the anonymous authors of the text that raised a feverish pitch for the painting have been less effusive? Potential bidders were regaled with its “ferocious … calamitous … talismanic” qualities. The most dog-eared book at Sotheby’s is clearly Roget’s Thesaurus. (Maybe no one bothers to read these catalog entries anyway.) As for the celestial studio, of one thing we can be sure: in the after-life artists are working harder than ever ... earning money for everyone else.

A few weeks ago, I bought a work by a younger artist from a storefront gallery in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. Accompanying the sale, and contingent upon it, was a contract that stipulated the art could not be sold for seven years from the date of initial purchase and that, when and if it was sold, the owner agreed to pay the artist or his heirs 15% of the re-sale price. This seemed entirely agreeable and, wondering why all artists and their representatives don’t pursue a similar example, I happily signed. Now, I have no idea to what extent, if at all, the price of this work will increase, but let’s say, for argument’s sake, that it ends up in the ultra-posh neighborhood of $110.5 million. An eventual 15% payment in return would add up to more than $16 million.

Now that’s a lot of money, but none of which I would have likely earned on my own, and so it would not, in actuality, be taken away. How would this count as a real loss except in one’s psychic ledger, a place where what is owed is imagined and what is rendered is never enough? As I rode the New Museum elevator back down to the lobby, my mind began to turn this all over in descent. What if there was a 12-step program for collectors, and not with any of the bogus overtones of higher powers, so-called?

What if, rather than demonize collectors as simply addicts, bad apples, incorrigible, beyond saving from themselves, we saw them as suffering from a disease that, with guidance, they may overcome, and thus return as productive members in our society of art? Here, then, 12 steps to take, one at a time, “baby steps” at first, gradually instilling confidence to stride purposefully toward a more meaningful relationship with art and artists, to see culture as something to which we contribute rather than deplete.

1.

Admit powerlessness over the addiction to money. Collectors who sell risk being seen as dealers, as do curators whose shows are too commercially linked. In the worst case scenario an exhibition comes back to haunt us, appearing as if it had been—we gasp in mock-horror—an auction preview all along!

2.

Acknowledge that the financial value of an artwork is not equivalent to its lasting, historical value. With contemporary art, that which is yet to be historically tested, art’s place is in every sense temporary. What you see in museums today may not necessarily be on display in museums tomorrow—“tomorrow” understood as twenty years hence, for twenty years is the least amount of time before any period will begin to enter history. Think about that when selling in 2017 what you consider to be an important work from 2015.

3.

Avoid peer pressure. When you go to the house of another collector and see works by artists you've already seen in other homes, this is not consensus. They are following one another. This is ovine, at best. Never buy the art to which everyone else flocks in a given moment, since the moment will inevitably pass. Don't be sheepish. Trust in your own instincts, and don’t let anyone pull the wool over your eyes.

4.

Take personal inventory of your relation to art and artists—and thus to life—rather than seeing a collection as so much inventory to be sold. When you see others sending art to auction prematurely, learn from their mistake.

5.

If you have sold for immediate personal gain, and not out of true need, admit to yourself, and another person, the wrongs done.

6.

Make a list of those wronged and be willing to atone for your transgression. Reparations!

7.

Believe in art, not in artifice: auction results, get-rich-quick schemes, consultants who, in a very slow week, will recommend almost anything. Hip today, hype tomorrow.

8.

Never cede self-control to higher powers—the market and the auction houses, driven by the all-mighty dollar, manipulators who rely on temptation, guarantees in a world where there really are none (isn’t most commerce a bubble over-inflated?), and promises they will never be held to.

9.

Be ready to accept responsibility for your behavior, your shortcomings: the true higher power is entirely within yourself.

10.

Fund the further purchase of art, providing needed support of generous patronage, with your own hard work, rather than using artists to bankroll so much skullduggery.

11.

Seek enlightenment by way of the art you become custodian for, living with it, sharing it with others and ensuring that it will be passed along after you have passed on, as it becomes increasingly beyond the reach of museums.

12.

Carry the message of the 12 Steps to others in need. Amen.