Looking at Photographs of Marilyn Monroe Reading

Audrey Wollen

February 25, 2019

There are more photographs of Marilyn Monroe reading than there are of her naked. Almost always, these images are captioned with a kind of perky can-you-believe-it paternalism. “Those books aren’t just for show!” “Despite her reputation as a blonde…” The public seems permanently surprised at her literacy, even when we are making a show of not being surprised. Just as Freud said every negative statement includes the wish of its positive, every Instagram post that insists hotness does not prevent intellect only reasserts the unreliability of its claim.

Beauty is a lot easier to prove than intelligence. And as Marilyn Monroe reading continues to be breaking news—a constant buoy for the shipwrecked listicle or uplifting aside—her nudity, once news that threatened to break her, remains established, endlessly familiar. I’m not sure why we insist that her reading scandalizes, even though by now, nearly sixty years after her death, it has become common knowledge.

In 1999, Christie’s auctioned off nearly 400 books from Marilyn’s personal library, a roster of classics ranging from Proust to Hemingway, which publicly solidified her intellectual identity and provided hard evidence against all those who claimed the plentitude of reading photographs were staged.1 But staged, of course, they were. They are hardly a homogenous document of fact; taken across decades, their only consistent element is the subject (Monroe), the act (reading), and the light, the aura that emits from the promise, the flattened proof, that beauty is real. Some call this being photogenic. Feminist accounts of Marilyn Monroe often take great trouble to declare the photographs’ candid status as a way to defend her ability to think, as if to pose with a book is to admit one cannot read it. But it is the slipperiness of their authenticity that make these photographs so mesmerizing.

To understand why there is such sustained, cultivated disbelief in her smarts, we must first understand how we came to believe she was dumb—iconically so. The dumb blonde trope is now a convenient schtick many actresses can slip on and off at will, winking at a lineage of platinum predecessors with every breathy “Oops!”, but then, in the late ’40s and early ’50s, Marilyn Monroe was pasting together a public identity of bit parts, pin-ups, and gossip rags, with hardly a cliché to rely on. Jean Harlow’s Bombshell (1933) and Betty Grable’s war-time success had paved the way for a busty blonde sex symbol through times of conflict, but post-war desire had yet to be pinned down.

The sex appeal of Harlow and Grable were both keyed to the subtle historical shifts of their moment: Harlow, a dangerous vamp, oozed through the sticky moral dilemmas of Depression-era glamour and excess, whereas Grable skipped into the next decade with the energetic pep of state sponsored nationalism, a girl next door who rooted for the good guys as the U.S. joined WWII in 1941. Neither blondes were particularly dumb, although Grable’s wide-eyed enthusiasm sometimes verges on the childlike. So why did Marilyn take on the mantle of artfully eroticized stupidity?

The archetype Monroe would come to define was barely sketched out as she began acting. Her first appearances are mostly as one-note sex objects: she swans in, heads turn, she introduces herself (already, though, her cadence and speech pattern are slanted, tilting, put-on), a joke is made at her desirability’s expense, and she swans away again. She doesn’t have enough lines to be intelligent, or stupid; at first, she is nothing but there.

In 1952, Howard Hawks cast her in Monkey Business, starring Hawks’ favorite Cary Grant and an Astaire-less Ginger Rogers. She plays scientist Grant’s sexy secretary, in the first example of what “would become her fixed type: the dumb, childish blonde innocently unaware of the havoc her sexiness causes around her.”2 Monkey Business was co-written by Ben Hecht, Charles Lederer, and I.A.L. Diamond. Charles Lederer would go on to write Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, I.A.L. Diamond would write Some Like It Hot, and highly political Ben Hecht would ghostwrite Marilyn Monroe’s autobiography My Story, which wasn’t published until 1974, after both were dead.3 Hecht’s version of Monroe’s life set a cultural precedent for every future biography.

The intersection of voices that would mold the public Monroe began through the easily ignored, screwball antics of Monkey Business, and a group of friends who, on the surface, seemed to be the opposite of Monroe’s public persona: markedly male, Jewish, whip-smart. The next year, Hawks would direct her in the epoch-defining Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: this time, however, the dumb blonde is the star.

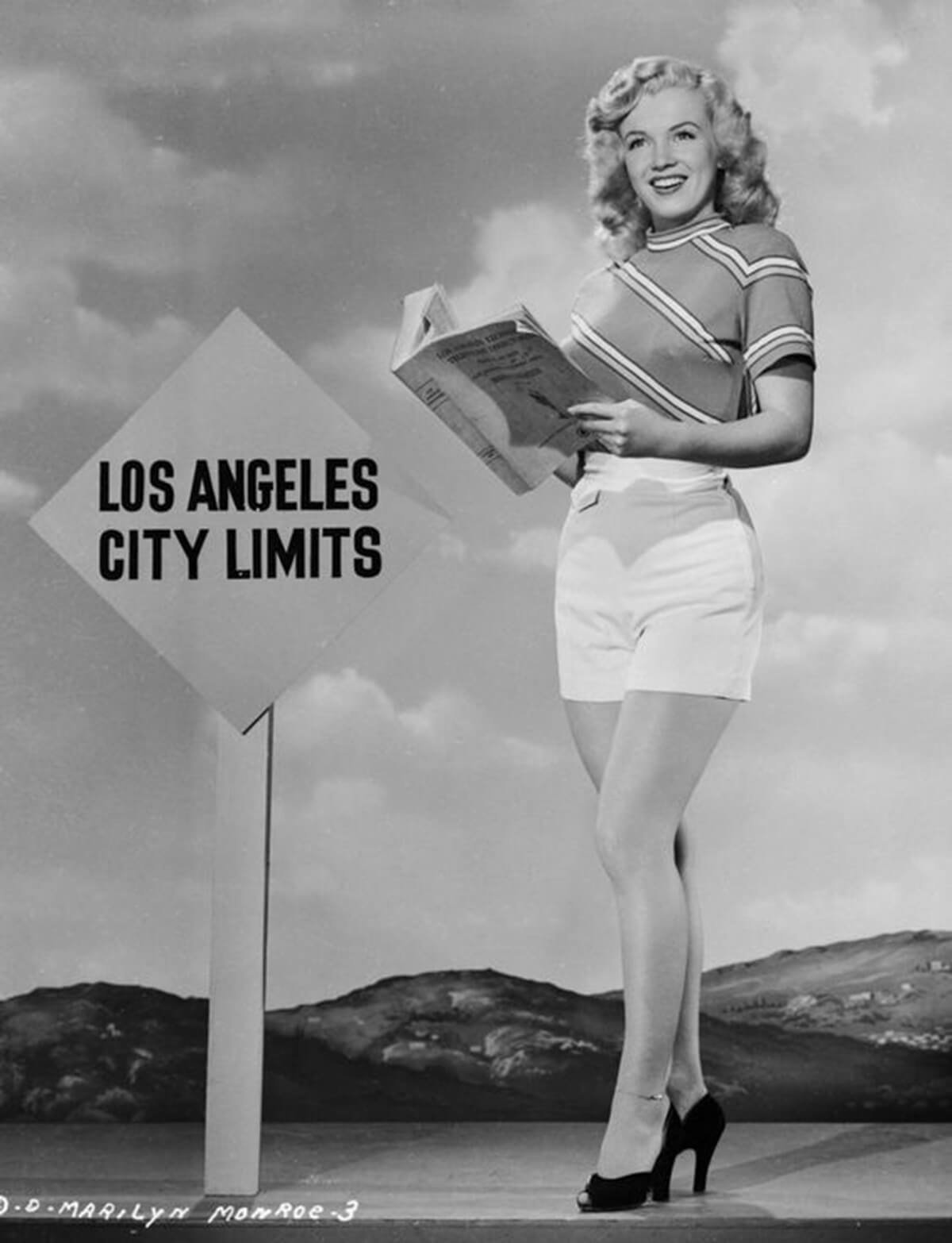

The earliest photograph of Marilyn Monroe reading is undeniably staged. It is 1948, Monroe is still surviving entirely off of modeling despite an acting contract at Columbia, and her hair is still a honey-colored blonde, shoulder length with syrupy curls. She has yet to bleach out her markers of age, the platinum that combines both the feathery soft hair of toddlers and pale tresses of the elderly. With every brush of peroxide, linearity burns away. She’s only 22 here, and she still looks it. She stands on a sound stage, with a plywood vista behind her, rolling California hills. A miniature street sign comes up to her hips: Los Angeles City Limits. This is a girl on the edge of something. Monroe, in shorts, holds a phone book open in her hands, but she’s not looking at it, she is smiling into the distance, as if surveying the unknown city before her.

The title of the photo, taken by Ed Cronenweth, is “Marilyn Monroe reading an L.A. telephone directory near the Los Angeles city limits.” Reading is a loose term, as is city. She is clearly not reading, just as she is clearly not at the corner where desert road meets incorporated pavement. She is not a Hollywood newcomer—she was born Norma Jeane at Los Angeles County Hospital, right off where the 10 meets the 5. She’s probably listed in the phone book she’s holding. It is not the fiction of the image that interests me—when did we ask pin-ups for realism? —but rather, the flagrant neglect of the image’s duty to convince us of anything.

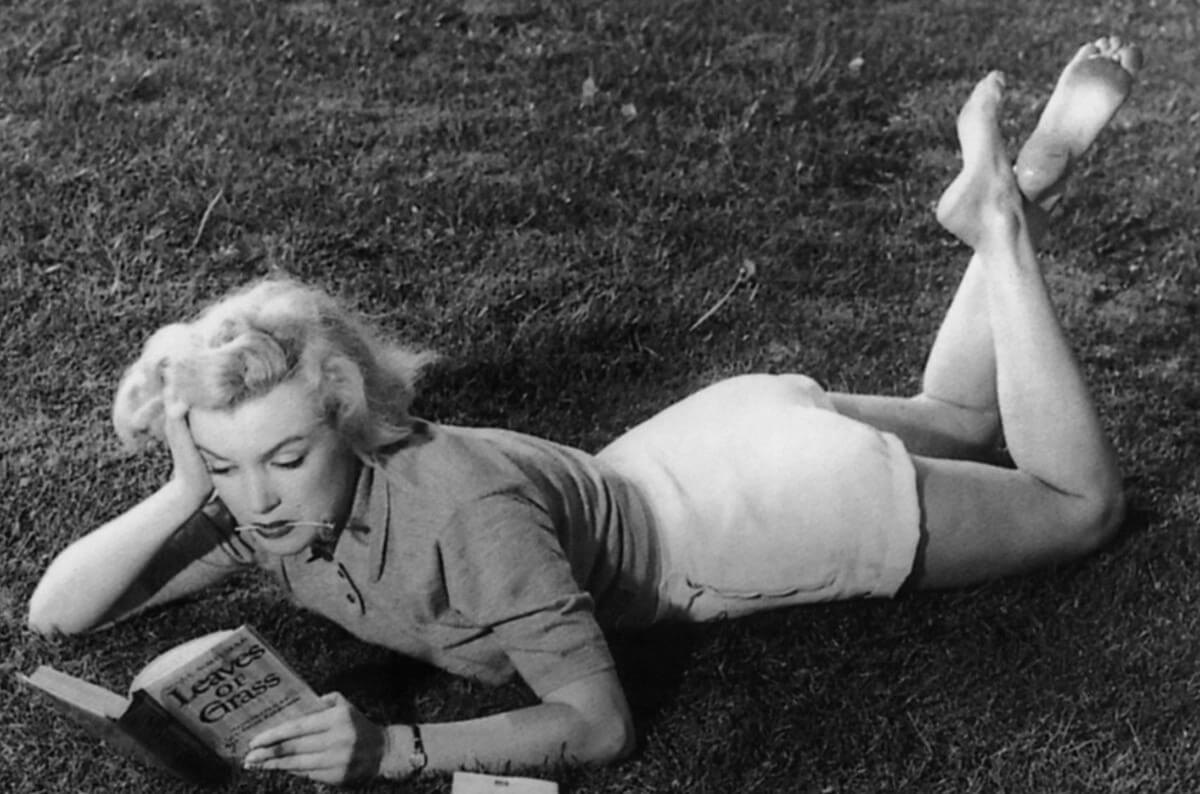

There are two photographs of Marilyn Monroe reading Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, taken roughly a year apart, by two different photographers, each presumably unaware of the other. The first, by Dave Cicero in 1951 for Love Nest publicity, shows Monroe lying on her stomach on a lawn, with her arms propped up, supporting her head, her legs bent and crossed, soles towards the sky—it’s the way I used to read on the living room floor as a child, rocking my feet back and forth (fig. 2). A blade of grass is in her mouth, her hair tousled. She is reading with concentration. Her brow is almost furrowed. The complete shoot includes a photograph presumably taken right after this one: there, she is lying on her back on the same lawn, rolled over and splayed out, smiling, her thumb still holding the Whitman open, but we can no longer see the title. The book mirrors her body: spine up or pages outstretched, she has only two modes, closed or open.

The second photograph was taken by John Florea in 1952. Monroe is at the Beverly Carlton Hotel, where she lived at the time (fig. 3). A plush, satin quilt covers the sofa bed where she reclines like a cloud; behind her is a shelf full of books, framed photos, small treasures. The cover of Leaves of Grass is more obvious here. She holds it at an angle out from her face, directly turned to the camera. Her expression is a little forlorn as she reads. It’s the same copy—hers.

Both photographs circulated widely at the time, promoting the seven different movies she appeared in between 1951 and 1952. Yet Walt Whitman’s place in Monroe’s public image continues to waver. Speculative biographer Sam Staggs wrote in his fictional account of Monroe, “Walt Whitman was her favorite poet… She often read Whitman for relaxation. The rhythm of his long free verse lulled and stimulated her at the same time.”4 The jubilant sexuality of Whitman’s content is overlooked for the “rhythms” of his form: for Stagg, she reads the sounds of the words, not the meanings.

Arlene Dahl, an MGM contract actress who reached brief fame in the early 1950s, has been quoted telling a Monroe-Whitman anecdote across decades: Dahl is at a party, in the corner with Fred Astaire, Clark Gable, and sometimes JFK, the story reliably changes with every re-telling, and the group is discussing Walt Whitman. Dahl laughs, “Marilyn happened to overhear the name ‘Whitman’ so she slunk over to the three gentlemen standing there… and she said, ‘Oh! Whitman! I just love his chocolates!’”5

Whitman (poet) becomes Whitman’s (chocolates), and Monroe shows her hand of blank cards. It’s impossible to know whether or not Dahl’s story is true, but it’s a good story, good and mean, and Monroe’s familiarity with Whitman only reinforces her role in its creation. As Sarah Churchwell points out in her book, The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe, Marilyn’s dumbness was often “comedy based on wide-eyed literalism, on non sequiturs and misinterpretation.”6 The best examples of her “literal-mindedness,” as Churchwell puts it, are sexual (What does she wear to bed? Chanel No.5. What did she have on during the photo shoot? The radio).

The Whitman/Whitman’s misinterpretation is witty, not only as word play, but as meta-comment on her own body as a symbol of national excess and desire. While the men discuss American poetry, she is eating American bonbons. In a different post-post-war moment, twelve years after 9/11 and a four-trillion-dollar War on Terror later, Lana del Rey releases an Americana-saturated short film, Tropico (2013). Adam and Eve (played by a male model and Lana herself) meet Elvis, Jesus, John Wayne, and Marilyn impersonators in a Technicolor Garden of Eden.7 Lana sings, “I sing the body electric,” quoting Whitman,8 swaying under the tree of knowledge, “Diamonds are my bestest friend,” she sings, quoting Monroe.9 Lana del Rey re-packages Walt Whitman like he’s Whitman’s chocolate, electric bodies wrapped in the pink cellophane of pop music. The distinction between poetry and commodity has collapsed. Marilyn questioned if it was ever there at all.

By 1955, the corrosive spiral of her playing with and against her own self-created stereotype reached critical mass and, in a radical and unprecedented move, she broke her contract with 20th Century Fox, relocated to New York City, and embedded herself within a thriving community of East Coast Jewish leftist intellectuals. In many ways, she was going back to the source. Monroe’s spacious capacity for escape and resurrection now seems fearless and alchemical: she made something out of nothing, and then turned around and nothing-ed all that something she made.

She fled the castle, or she kept conquering territory, depending on who you ask. From the height of Hollywood, she went to the theatrical stage; from the beloved baseball star, she went to the acerbic playwright; from the front page tell-all interview, she went to the psychoanalytic couch. The press, the public, and the studios all thought she had gone crazy. In the United States, in 1955 and now, nothing screams insanity like shacking up with a Marxist, believing Freud, and reading Dostoevsky.

The first significantly researched and comprehensive biography of Monroe, published in 1956 by Pete Martin, was titled Will Acting Spoil Marilyn Monroe?10 It was structured entirely around the open-ended risk of her decision to “be serious,” an innately untrustworthy aspiration in American culture. Martin’s title defines ‘acting’ as stage-acting only, implying that the twenty-four filmic appearances Monroe had accumulated in the past nine years of working was only an example of her ‘being.’ As the ditz, she was, in many senses, an obtuse form of working-class-hero: someone even the most uneducated could feel smarter than.

This new allegiance to the New York literati was a betrayal beyond a simple disturbance of sexual fantasy; she was no longer just “a little girl from Little Rock, [who] lived on the wrong side of the tracks,”11 a class identity and origin story upon which her gold-digger bimbo persona relied. Like gender, class is an embodied system of discipline: Monroe’s passage from pop culture to high culture is named by Martin as a transgression that spoils, as if she were a petulant child, or a piece of fruit.

This fear of intellectualism was a lingering effect of McCarthyism, which had purged Hollywood and New York of perceived dissenters in a shocking spectacle of power just a few years before. In 1955, the FBI opened their file on Monroe, which they would keep actively updated until her death: “Subject’s views, very positively and concisely leftist,” it notes.12 The words “positively and concisely” evoke a kind of alacrity and sureness—this is a rare gleam of lucid resolution in one of the most indeterminate public figures of all time. It is no coincidence that the spectacle of Monroe’s mental illness, drug addiction, and tragic fate gains ground in the public consciousness at precisely the moment she begins to identify as an auto-didact and politically aware person.

Her marriage to Arthur Miller was made out to be an unthreatening and cartoonish case of odd couple in the press (“The Genius and the Goddess,” “The Brain got the Blonde,” “Egghead weds Hourglass”) to distract from what was essentially political identification and intellectual self-fashioning by way of romantic partnership. If Marilyn Monroe was only ever understood in the terms of sexual desire, then who she chose to sleep with became one of her primary modes of communication to the public. Post-Freud yet pre-Foucault, she, of all people, understood that who and how you desire has material consequences.

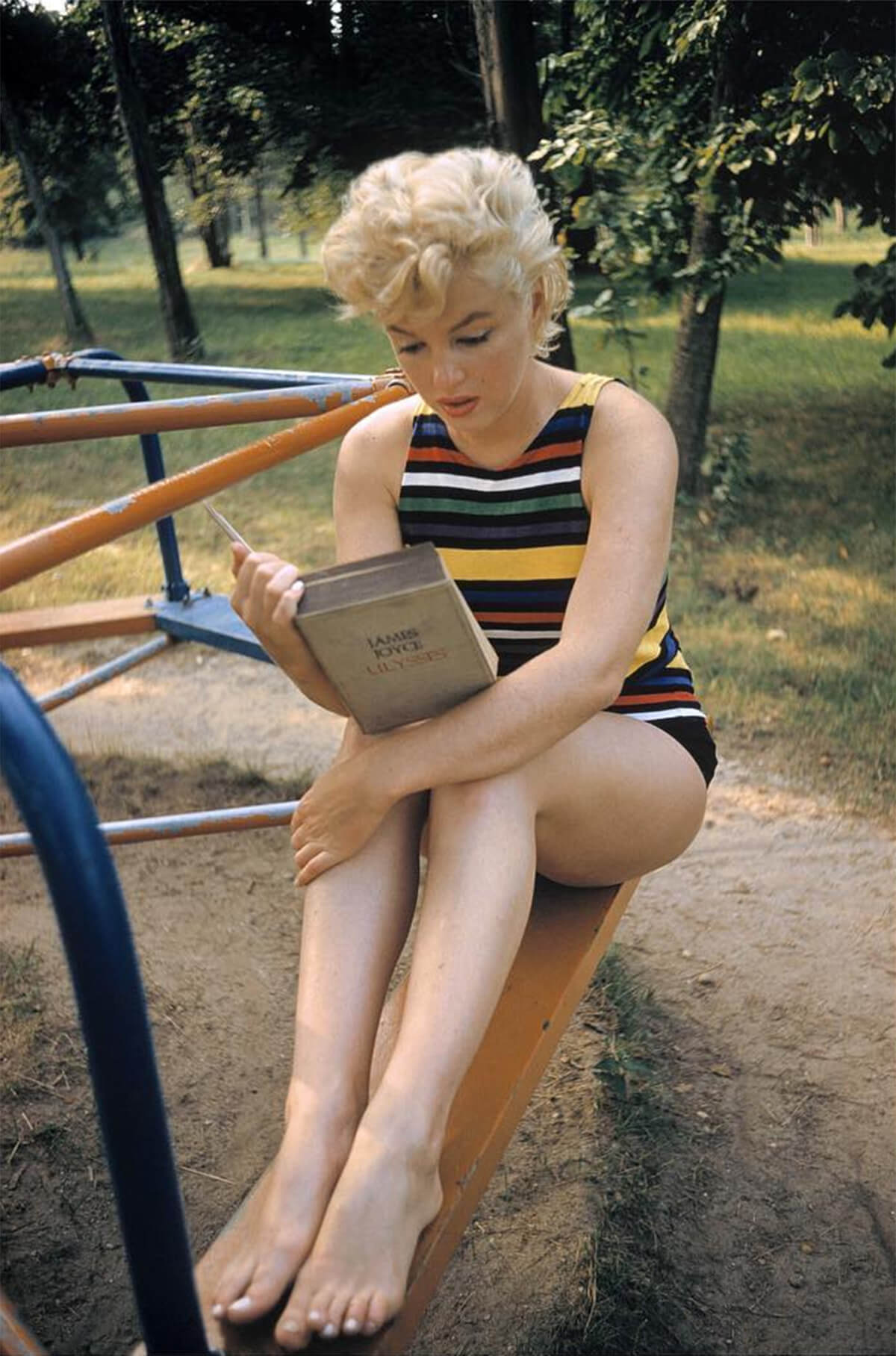

The most famous photograph of Marilyn Monroe reading relies on the iconicity of both reader and book (fig. 4). In 1955, on an impromptu photo shoot in an empty Long Island playground, Eve Arnold captured Marilyn perched on a rusty children’s round-about, reading James Joyce’s Ulysses.13 She is near the end, where the novel culminates in Molly Bloom’s embodied stream of consciousness. This section is also notoriously sexually explicit. Joyceans, historians, fans, feminists, and film theorists have spent decades in the thrall of this photograph: what does it mean to have two such legendary symbols of the “history of sexuality, its censorship and its contestation, its inscription and its representation” meet unexpectedly in a candid shot at an abandoned playground by the beach?14

In many cases, rather than proving Monroe’s intellectualism, the image’s “naturalness,” is used conversely to extrapolate on her naiveté: she couldn’t have comprehended her own meaningfulness, she must have stumbled into this iconic convergence of cultural objects. The background of children’s playground doesn’t help. Anyone can hold a book open. In a 2014 interview with Time magazine, Richard Brown, Joycean scholar, was asked if he believed she was “actually reading it” (emphasis in the original). He responds, “If you see someone in a picture reading a book, then they are reading that book.”15

The question snags on the shared problem of not knowing exactly what reading feels like for other people. Is it something one can fake? Is reading the same thing as understanding? Is understanding sufficient? Where, in the body, is such a process held?

In the photograph, I see three women, even though only one is visible: Eve, Marilyn, and Molly Bloom. Together, half-way home in the liminal space between city and country, fiction and reality, image and body, they merge in a document of pleasure. My best friend has a postcard of this photo up in her bedroom; I once had it as my phone background. I looked at it every day. It promised that beauty and meaning were not mutually exclusive, that fantasy didn’t have to compromise. It offered a set of paradoxes: glamorous, desirable, and well-read. Adult, yet childlike. A woman, intellectual. We could be all these things!

This was a false promise, in many ways, and so we countered by cultivating the fictional within ourselves. Tending to our impossibilities, we offered those around us both the negative, the zero, and its accompanying wish. That’s what Marilyn gave us: the “not” and its opposite. Pretending to read, and reading, all at once.

- Christie’s, The Personal Property of Marilyn Monroe: Auction Catalogue, (New York, Christie’s, 1999).

-

Sarah Churchwell, The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe, (New York, Picador, 2005), 53.

-

Marilyn Monroe and Ben Hecht, My Story, (Langham, Maryland, Taylor Trade Publishing, 2007).

-

Sam Staggs, MMii: The Return of Marilyn Monroe, (New York, Dutton, 1991), 75.

-

MarilyNo5, “TCM ‘Word of Mouth’ – Marilyn Monroe”. Youtube video, 1:30 min. Posted September, 2011. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xs4XNkWu1Q4).

-

Churchwell, Many Lives, 50.

-

Lana Del Rey. “Tropico”. Youtube video, 27:08 min. Posted December, 2013. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VwuHOQLSpEg&t=385s).

-

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, (New York, Penguin, 2005), 116.

-

Or, technically, a purposeful misquotation, as Marilyn Monroe sings, “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, whereas Lana adds the coy “-est” to the “best,” accentuating the little girl, or the California girl, intonation.

-

Pete Martin, Will Acting Spoil Marilyn Monroe?, (New York, Doubleday, 1956).

-

This is a lyric from the Monroe’s opening song, “Two Little Girls from Little Rock,” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

-

‘FBI monitored Monroe for Communist links,’ Guardian, 29 December 2012. As cited in: Jaqueline Rose, Women in Dark Times, (London, Bloomsbury, 2015), 117.

-

Eve Arnold, Marilyn Monroe: An Appreciation, (New York, Alfred A Knopf, 1987).

-

Griselda Pollock, “Monroe’s Molly: Three Reflections on Eve Arnold’s Photograph of Marilyn Monroe Reading Ulysses,” Journal of Visual Culture, 15.2 (2016), 203-232.

-

Richard Conway, “On Bloomsday, Marilyn Monroe Reading Joyce’s Ulysses,” Time Magazine, June 16, 2014. (http://time.com/3809940/marilyn-monroe-james-joyce-photo/)