Should Artists Shop or Stop Shopping?

Sheila Heti

May 21, 2018

While doing research for this piece on the artist Sara Cwynar, I came across an interview which showed photographs of her studio. One of the photographs featured drippings from candles—she was melting candles, and layering the drips, and the drips would eventually be moved and put on a canvas. In a text accompanying the photograph, the journalist noted that Cwynar “tends to buy her source material from dollar stores, drug stores, eBay, and, recently, candlestock.com, a candle company based in Woodstock, New York.” There was a link to candlestock.com embedded in that sentence, so I clicked on it. Then I spent ten to twenty minutes looking around candlestock.com hoping to find something to buy.

Whatever candle would end up in my house would be a symbol for me of being somehow more special and better than other people who bought their candles from Bed, Bath and Beyond, or Amazon, or Ikea, or any other place, for I had sourced my candle from an artist who used candles in her art, so clearly knew the best candle source. As I was looking at candlestock.com, it occurred to me that I didn’t know which candles she bought, so she might end up with a more authentic candle than I would, while I would end up with the sort of candle of a person who was rather mediocre in her tastes, reaching for the symbol of a candle that would secretly telegraph only to me that I was in-the-know.

The difference between me and Sara Cwynar, I reflected, was that she was not buying candles to display in her home, to prove herself to be the sort of person who knew the best place to buy candles, but rather was buying them as an artist buys supplies: to use them for some other purpose. She was going to transform them, make them into something greater, something more her than candle. Whereas I would be, in buying a candle from candlestock.com, just a tourist in the life of art, the same way I feel people who buy saccharine journals, with pretty fabric covers festooned with a ribbon and gilt-edged pages, are tourists in the life of writing.

Sara was not buying candles at candlestock.com, a candle company based in Woodstock, New York, to pose before herself, or others, but because candlestock.com sold cheap drip candles in many colors. She would mess with them, break them down—not display them like status objects, conveying her grand leisure, the leisure of a woman who can source the best place to buy candles, a place that other women of leisure haven’t discovered yet. This second person would be me. But who was I performing for? I am not on Instagram, showing off my life. Nobody comes to my house. I would be showing off my candles for me, and these candles would convince me that I had the intelligence, taste, and money, to source the most authentic sort of candles, thus proving myself to be superior to other women—proving this to myself for only a day or two—before the candles would become like everything else in my apartment: an extension of what I actually am, not what I hope to be.

All that time I was spending on candlestock.com I should have been spending on real research—reading interviews with Sara Cwynar, and looking more closely at her art than I was looking at the photographs of candles. How could my priorities have become so confused? Only because in some circles I have already proven myself to be enough of an intellectual to talk publicly about art, while I have still not yet proven to anyone that I am the sort of woman who knows how to furnish her house with the right sort of candles. All these thoughts were running through my mind as I was paging through candlestock.com. Then I shut down the website, having bought nothing, and I returned to my task, which was writing this lecture, which I had promised the gallery would be titled:

Should Artists Shop or Stop Shopping?

What can you do with no time and no money? asks the narrator in Sara Cwynar’s video, Soft Film. Who is this person who has no time and no money?

The artist has time, but no money. The consumer has money, but no time.

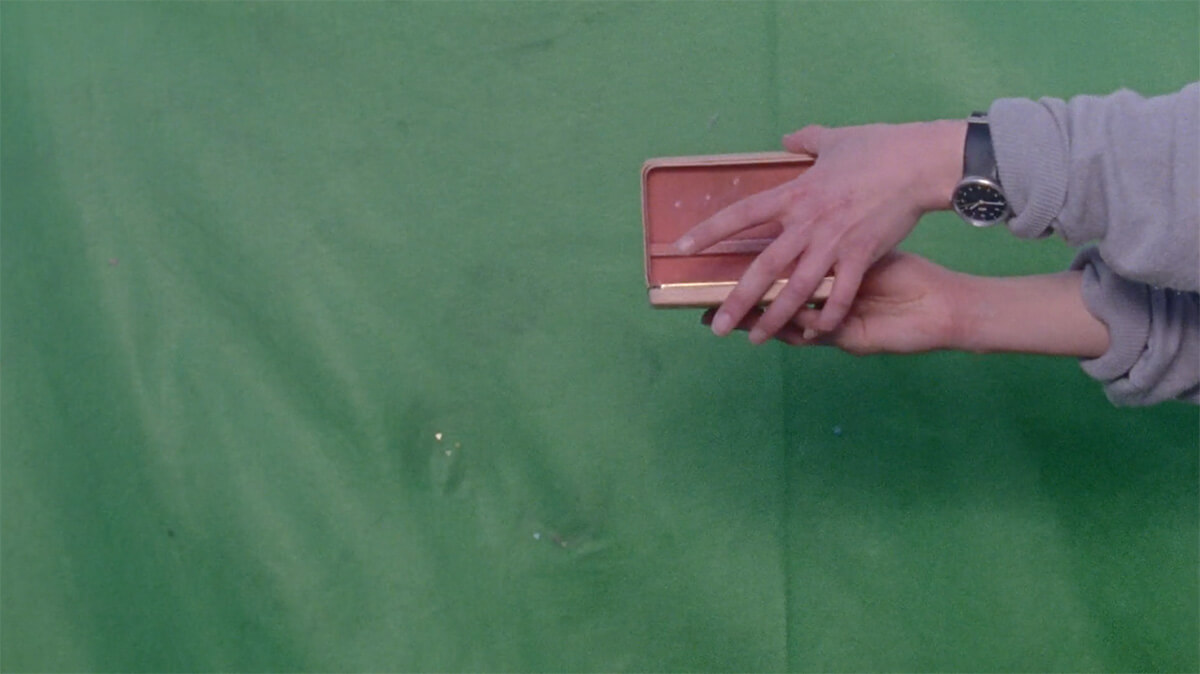

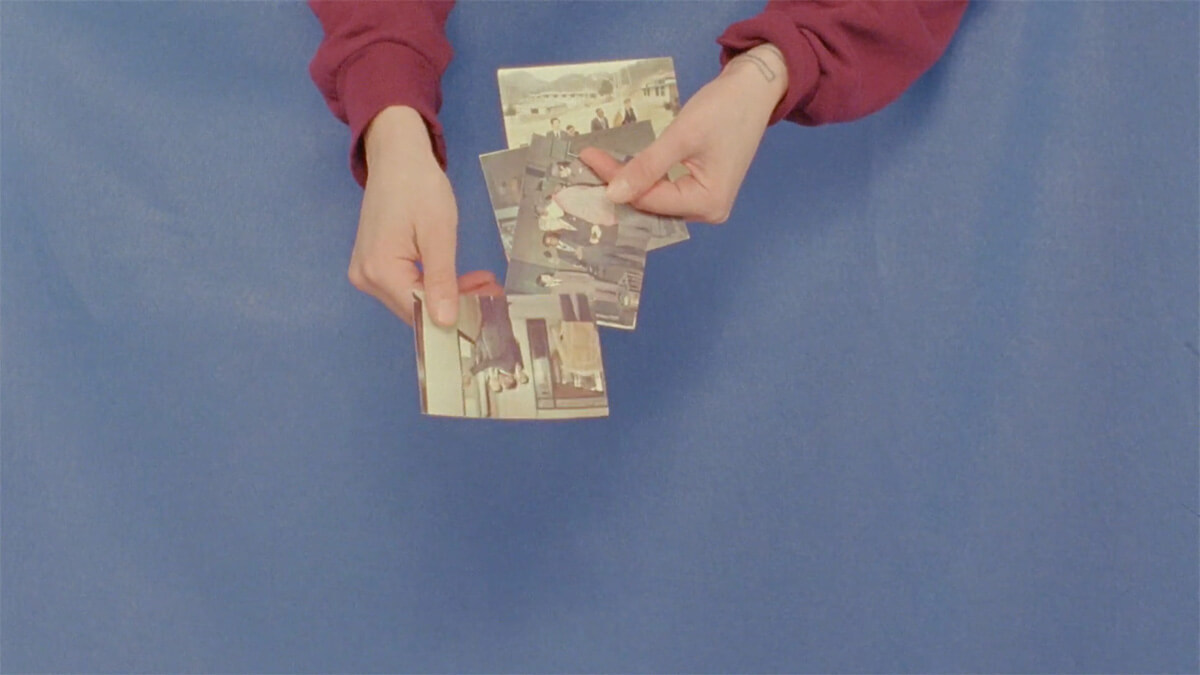

To create her art, Sara Cwynar spends money like a consumer: she shops on eBay, she goes to dollar stores, she collects, she builds up her collection. Like the most distracted hoarder, she throws all of what she collects onto her floor in piles. There is some organization to her cataloguing system, but not much. Or as she told Interview magazine, “There is an organizing principle! But it’s just not very articulate, nor very good.” To build her work, she “shops” from her floor, from the items she has collected because they appealed to her on a deep level—they stirred something in her person. Take the old velvet jewelry boxes she buys from eBay, with colors that have faded over time. They have changed more through time than the jewelry they once held. These boxes aren’t supposed to be the focus of our attention: it’s the jewelry that’s supposed to be. But Cwynar wants the boxes. She is not a consumer with money but no time. She is an artist, with time but no money. The jewelry costs ten thousand dollars. The boxes cost ten.

So she has a bit of money, but more than that, she has time. She has time to buy things on eBay. And she has time to figure out what she wants and needs to buy. She has time to sift, to be led by her aesthetic sense, and her intelligence, and her vague premonition of what she will wind up making.

The non-artist consumer, who has money, but no time, buys what they are told to buy, or what they see other people buying, or what they imagine are the best things to buy. They do not buy according to some finely-chiselled inner compass, the way that Sara buys, or the way that a writer chooses her words.

Most of us buy to project something about ourselves to the world of people who witness us, or to tell ourselves that we are the sort of people we want to be. But Sara’s time-rich consumer activity is different. It is different because the things she buys never seem expensive: a postcard with the Twin Towers on it; dishwashing gloves just the right colour of red. They are never expensive because she is the only one who wants them. Things that are expensive are the things we all want. If we all had the time to want what we in particular want—to figure out what those wants might be, then spend our time finding them in stores or online—we would cut down our discretionary spending by so much... But we have other things to do. We are not artists. Being not-artists, we buy what others buy, and spend so much more than we should.

Whenever something costs a lot, it’s because everyone wants it. The reason you want it is because everyone wants it. And you want it because it costs a lot—you want it more because it costs a lot—because its costing a lot is a sign that it is wanted by many people. The fact that you can afford it and others cannot makes you feel like you are part of an elite circle that not only wants it (like everyone does) but can afford it (like only some).

To turn yourself into an artist, stop buying things that cost a lot. Buy the things that other people don’t want—that only you want, because it’s the right shade of green.

“The soft texture gets me here,” the narrator of her video says, while her hands fondle the jewelry boxes. “Gets me here” means “gets me to the place of having bought these boxes.” The soft texture gets me here. But here also means something more, for buying these boxes has got her here—to the place of standing in front of a camera in her studio, holding many old and faded jewelry boxes—here is the place in her process where she finds herself fondling the boxes, opening them, letting jewelry fall onto the floor out of them—the soft texture gets her here, to this very moment in her art-making.

I cannot say of any consumer product I have bought that it “gets me here,” if here is someplace new, different from the old one. For me, a consumer, it is the reverse: Buying keeps me in one place—the same place I was in when I bought the thing. I can only get to a new place if I stop buying—stop shopping on Amazon—stop succumbing to whatever material needs seem to emerge in the day. Buying keeps me here, in a certain state, a state of waiting (for the thing to arrive), a state of limbo (between my life as it is now, and the life I imagine I will live once I have it), a state of unreality, of wishful thinking, of magical thinking (that my life will be different once it arrives), a state of disappointment (when the thing I bought is absorbed into my life like everything else, and does not distinguish itself as new), a state of need (to buy the next thing that will lift me out of this here.) But what is this place I am in, and trying to escape? What is this here, but shopping? My home, and the computer on which I write, and the phone in my pocket, everything around me—has become a shopping mall. I am here in a shopping mall and I can’t get out. I can only get out if I stop buying things.

I can only get out if I buy in the way of an artist—if I buy like Sara Cwynar.

*

The narrator in her video says, “I can’t sleep so I comb eBay. Of course I can’t sleep. There is too much to look at.” I am not kept up at night, like Sara Cwynar is, by all there is to look at on eBay. I’m kept up at night by my greed—I’m kept up by the idea that these things on eBay could be mine.

*

Shopping is a form of creativity. When I am writing well, I feel no need for shopping. The times in my life I have shopped a lot, it is because I have not been writing.

Shopping is selecting. Writing is selecting.

Shopping is choosing the best thing. Writing is choosing the best thing (the best thing to write about, and the best way of writing it).

Shopping is articulating oneself through one’s choices. Writing is articulating oneself through one’s choices—choices made while writing.

If I tell myself I must not shop, I feel a deprivation and a fear. But if I actually do not shop, I feel self-contained and free. If I don’t write, I feel deprivation and deadness.

Shopping sucks the creative energy out of my body—energy which could be put into writing—which I have instead put into shopping. Shopping makes me lose money. Writing earns me money. Writing gives me a feeling of satisfaction after having done it. Shopping gives me a feeling of nervous tension, anxiety, excitement and dread. When I have written on my computer, I have my riches there in front of me. When I have shopped online, the riches take days or weeks to come, and when they arrive, they no longer feel like riches. They are never all I hoped they would be. They are objects. They are not hopes. They are not wishes. They are not dreams. Writing—have been written—remains a hope, a dream, a wish. Why don’t I write when I feel like shopping? For Sara Cwynar, shopping is necessary to make her art. It is not necessary for me. She has made shopping necessary for herself. She has made it something else.

When she shops for postcards, candles, and industrial tape, does she feel the way I do when I write, or does she feel the way I do when I shop? Or does she feel some other third thing?

What would it feel like to be like Sara Cwynar; to every day buy a postcard of the Twin Towers on eBay?

I buy a spiralizer, running shoes, vitamins, books, a pregnancy test, white t-shirts, light bulbs, an iPhone case, a milk frother, batteries. I do all my shopping on my computer. I do all my writing on my computer. Sometimes I shop from my gold-tone iPhone.

“As soon as you buy something, you lose the power to buy something,” says the narrator in her video. Does this mean you lose the power to buy something because you’ve spent the money you’d need in order to buy the next thing? As soon as you buy something, you lose the power to buy something. I think the statement is more philosophical than that: as soon as you have the thing, you have lost the power to buy the thing. You cannot buy what you already have. It is the power to buy it that feels intoxicating. The thing—arriving as it does in the mail—is no longer (once you hold it in your hands) throbbing with your power to buy it, like you were throbbing when you added it to your cart. It is now inert with being owned.

*

“Objects are shocking because they stand in our way,” the narrator of Sara Cwynar’s video says. This may be true of some objects, but consumer objects are not, for the most part, shocking. They do not stand in our way. They are inevitable because they are put in our way, and when they arrive, their inevitability is all there is. That’s all right, we quietly think, after we unpack the item and grasp it in its inevitable banality. This is not a structural problem. It’s that I have not yet bought the right thing.

*

The narrator in Sara’s video says, The way that the things that were the most stylish are the ones to warp the most quickly.

A consumer like me wants the things that are most stylish, and which consequently warp the most quickly.

The artist who buys for her own reasons and for her own pleasure, makes art out of the things she buys. They are transformed into her art, and art is the opposite of a most stylish thing that warps most quickly. Good art is most stylish and it never warps. Or it is unstylish when it first comes into the world, but it never warps the way fashion warps. The world warps to accept it.

Art holds within it the moment in culture in which it was produced—it preserves that cultural moment with all its contradictions and flux, so we can look at art, and understand the time it was produced in. Good art doesn’t warp, grow gaudy or kitschy with age. Bad art warps. It grows as gaudy and kitschy as an ad in a magazine, or as a jewelry box on eBay. Bad art is like a stylish consumer product. Why does it warp? Why does it look so desirable one moment, then so awful the next, while good art is stable, and sits as itself, forever, in a culture which is ever warping?

In her video, she asks, “How do things become a glitch instead of an intention?” A glitch is what warps. An intention never does. A glitch is buying something impulsively on the internet. By the time it arrives, it has warped.

*

A sentence from Sara’s film:

...an impulse to buy because this object truly is one-of-a-kind...

A sentence from Sara’s film:

...because it cannot be consumed, only contemplated...

A sentence from Sara’s film:

...pursue play... that’s what I’m going to do...

A sentence from Sara’s film:

...two thousand yards, one dollar fifty...

A sentence from Sara’s film:

...look at one thing at a time—just look, slowly, as if coming in from the side...

A sentence from Sara’s film:

Is the rose gold iPhone a totem? Does it signify an order? Maybe you won’t even remember it at all.

A sentence from Sara’s film:

Rose gold doesn’t need to be anything at all—just an idea in the air; something to look forward to...

*

I was corresponding with the poet Dorothea Lasky a few weeks ago. She teaches at Columbia University. She wrote me,

“My friend, Lucie Brock-Broido, passed away a few days ago. There are so many things to do because this just happened, but I feel I am too upset to do any of them, because I miss Lucie so much and am in this horrible nightmare state of shock where I am hoping I am imagining her gone and that I can just pick up the phone and call her. Then yesterday at 4:30 pm I taught my thesis class, where the students are making poetry books, and then went into Lucie’s office and took pictures, trying to preserve and process how she left her things. She was a collector of things, as I am, and I knew everything was particularly placed. How things were placed by her is something I wanted to preserve.”

I was struck by the idea that she wanted to preserve the way that Lucie placed things—that she felt this said something about Lucie, something that could not be said in another way, and so Dorothea felt she had to go in and photograph Lucie’s office. It wasn’t the things she collected that Dorothea was interested in—although she called Lucie “a collector of things,” but rather she was interested in preserving “how she left her things.”

A few emails later, Dorothea sent me a photograph of a corner of her own room at home. It seemed to be a white desk, with objects she had collected all arranged in a seemingly meaningful way: there were perhaps a hundred objects in the photograph: buttons, dolls, stickers, animal figurines, salt and pepper shakers, fortunes from fortune cookies, crayons, a mug, a tear-shaped mirror which dominated the desk, a tiny ship with sails. (As Sara’s video says, It is inevitably oneself that one collects, and I felt this when I witnessed Dorothea’s collection, as if seeing her in her nakedness.) Clearly every object in Dorothea’s photo had been thoughtfully acquired, and purposefully kept, and deliberately placed in some arrangement with the other ones. I told her it looked like a shrine. But while this shrine was just for herself, and ugly in some way—like the desk of a teenage girl, cluttered with objects of personal meaning that could mean nothing to anyone else—Cwynar’s arrangements of objects become works of art and beauty. Her arrangement is not just for herself—it is for us.

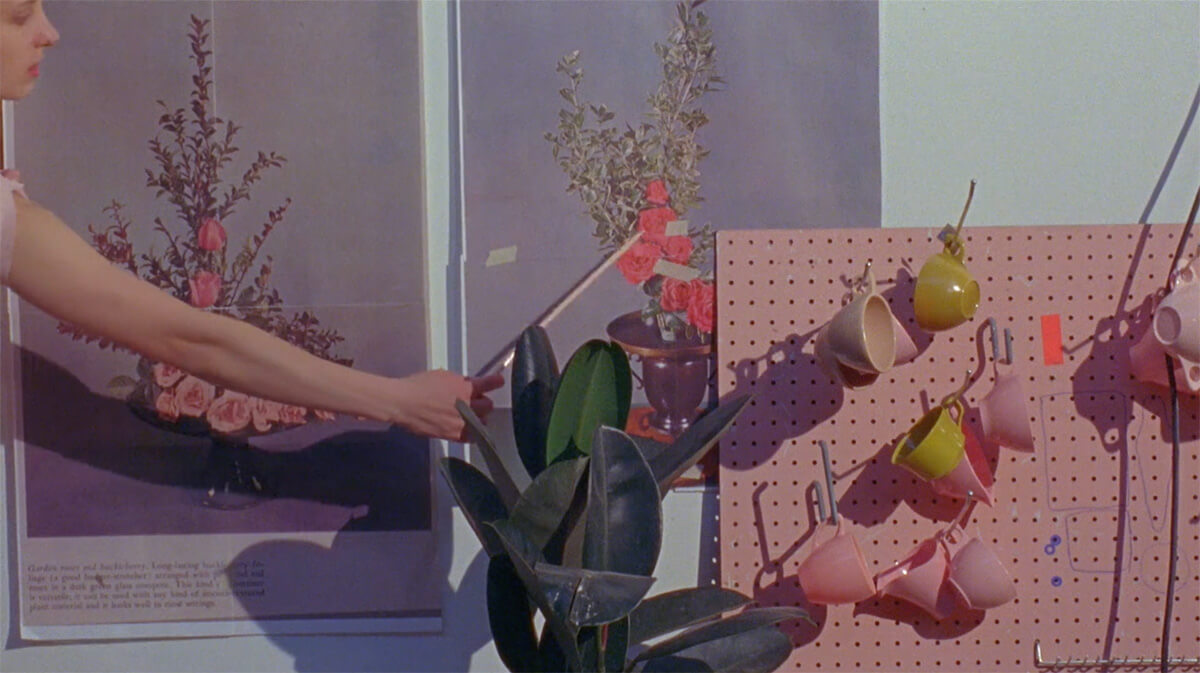

*

There is a world of objects collaged together which make up Sara Cwynar’s flower still lives—buttons, candles, fake apples, shoelaces, lightbulbs, books, straws, billiard balls, spools of thread, markers, paint brushes, toys—but the personal meaning they had for her (if they ever had personal meaning for her) has been stripped out of them. They seem meaningful only for their shape and color. They are at once what they originally were (those plastic gloves were made for washing dishes) and, in their new arrangement, have lost their original meaning (they’re the right shape and color for that space). One’s eye is constantly flickering between knowing the object, in all its banality, and losing a grip on its original purpose in favor of its current purpose: to be a thing of shape and color in a Sara Cwynar’s picture, to have an aesthetic relationship to the other objects there.

One thing we know about consumer objects is that they are only supposed to lose their meaning—to flicker, let’s say—in the way the seller wants them to flicker. The sneaker can flicker between being something you put on your feet and something that raises your status in the world, but the flickering ought to stop there. The sneaker is not meant to flicker between being a status object and a flower vase. It is not meant to flicker between being a shoe and something else that’s red. Of course once you’ve bought it, it will flicker between so many meanings: the meaning of when you wore it, or what your best friend said about it. The seller can’t help that. But until it is bought, the meanings it is meant to flicker among are incredibly policed—and the more expensive it is, the more highly policed.

The meaning of a rose gold iPhone is supposed to flicker between ideas of luxury and status and newness—of a glossy future currently being born—but not flicker anywhere close to the idea of the puke green and bright orange that were once as desirable as rose gold is now. No one is policing the meaning of the things Sara buys to populate her videos—the old tape cassette, the discontinued spool of thread—because they cost two dollars, used.

*

At first, in the video Rose Gold, we get the sense that Sara has dodged beyond the clutches of the rose gold iPhone—the grip of its terrible beauty. She is thinking about what rose gold means, but this is an intellectual or aesthetic exercise. And then the words come: I love the rose gold iPhone.

She is as overcome by lust and desire for it as we all are. In the moment of her saying that, it has become for her what it is for everyone. In the next sentence, she calls it a magical object: “Old divisions between people and things are confused in this magical object.”

The thing of this sentence is the iPhone, and the people in the sentence is our desire for it. The thing and the desire for the thing are confused. It’s impossible to think about the thing—the iPhone—without thinking confusedly of the desire for it.

“Rose gold is flattering to most skin tones,” her narrator continues, as if to apply scientific reasoning on why it’s so desirable for so many, these phones we hold up against our faces. Flattering to most skin tones! That is not the reason we want the rose gold iPhone!

Now her narrator interjects, “Who is the voice of authority here, and who is this object actually for?” The voice of authority is clearly Apple, or whoever does their marketing, while who is this object actually for? It is not for anyone except for Apple. It is not for us, us sorry suckers, who could do without the rose gold iPhone. It is exclusively for its money-maker.

The video ends, “Is the rose gold iPhone a totem? Does it signify an order? Maybe you won’t even remember it at all.”

*

A few years ago, I edited a book called Women in Clothes. It was collaged together from the responses of 639 women from around the world to a survey my co-editors and I had put together about why women wear what they wear. Just like Sara Cwynar’s work, the book, in part, dealt with the question of shopping—of collecting and displaying on your body—of what you chose to take from the world of objects, of which goods certain women find desirable, and why, and how they choose to arrange them—not on the studio floor, but the body. Many people answered our questions about shopping in ways you might imagine: most women seemed to know what they liked, and why they liked what they liked, and it all felt very personal, and very expressive of their lives and histories and likes and families and phobias and desires. If there was one thing that underscored the answers, it was that a woman’s choices were meant—she knew—to do one thing above all else: reflect her individuality.

One of most divergent answers to the survey came in the form of a pamphlet or manifesto by my friend, the visual artist Margaux Williamson. It was a 24-point treatise, and it is a good example of how an artist chooses from the world of things, versus how a consumer chooses. The way that Margaux suggests we choose our clothes is a very close corollary to the way that Sara Cwynar models choosing from the miles of stuff listed on eBay.

Here are some points from her piece, a manifesto titled How to Dress in Our New World:

We used to dress to show the real us, or the other us, or of course to stay warm or without shame; to show our sex, our carelessness, our professionalism, our nihilism, our money; to be camouflage, a glossy magazine, a protest sign. But now we see—this old game is only a game of playing matchy matchy with our souls.

The new game is to be misunderstood. And the new challenge is learning how to be misunderstood.

Being misunderstood makes everything easier. It makes clothing acquisition less time-consuming. The contemporary situation is taking up plenty of your time, no time to waste... We must find new ways to acquire clothing, new ways to show we are both of the sky and of the earth.

So now if you find a T-shirt on the street and it is 100% cotton, maybe it is time to put it on. That is a great find, to find cotton on the street, so far away from the fields. And though it probably advertises a bad system that you don’t believe in, everyone knows from your face what’s in your heart. And besides, our personal investigations are as valuable as our speeches. See what it is like to match your face with the bad system...

If a kindly older woman gives you a coat that makes you look like you’re on the wrong side of the money wars, wear that coat to your comrade or nemesis’ dinner party. If we can’t practice our beliefs and our empathy and our experiments over dinner, what is the point of dinner.

It might seem like, in the new world, clothes are nowhere to be found, but they are everywhere. In the desert, at the funeral home, in the garbage. There will never not be enough clothes. We made so many. Galaxies of factories were born in the name of individuality. Our person to clothing ratio spiraled out of control and the resulting great piles of clothes made more visible the meaninglessness of our individual lives on earth... Now, we must remember, the less effort we spend before that pile of production, the more meaning. It is not about finding the perfect you in that garbage heap, it is about economical movement and effort—what we can find here, at our feet—since you are very much you, and anything else is a juxtaposition, a gift.

So now, if you easily come across a dress that fits you like a glove, but makes you look like a stranger, remember, this is a fortune-telling game of meaning and ease—we must turn in the direction of what fits...

What we love now are worn things, things that have made it through experiences with what appear to be travel scars and thick skin...

Wash but do not make alterations... Make no adjustments beyond what scissors can do. If the shirt is too big, you will look young and poor. If the shirt is too small, you will look big and strong. If the shirt is much too small, leave it on the street for a smaller hunter.

It’s like the voice in Sara’s video says: “Why would you make anything new... when there is so much already?”

*

I look at etsy for the second time in an hour. I want everything I see on it! I like the feeling of wanting, and I hate the feeling of wanting. How can I be an artist on etsy, instead of a consumer? What rules can I make for myself, when I’m browsing or shopping on the internet, that will turn me from a consumer into an artist? That will make me not go broke?

I imagine the rules Sara Cwynar has for herself as the same rules Margaux has:

Don’t buy anything over twenty dollars.

Don’t buy anything new.

Don’t buy anything that you don’t plan to combine with something else, or change or alter in some small way.

Don’t buy something that doesn’t make sense with everything you already have. It should match or contrast with it all, in some way.

Don’t buy anything over fifteen dollars.

Don’t buy anything over ten dollars.

Don’t buy anything over five dollars.

Don’t buy anything over two.

*

When I follow these rules online, I find a world of stuff that looks like Margaux’s closet, and that looks like the objects in Sara Cwynar’s video.

*

Things that are already gone the same moment that they arrive, her narrator warns...

Which is the perfect definition of everything I order over the internet. They are gone the moment they arrive.

How can I remind myself, when I’m browsing online, that I don’t want anything once it comes? I want the looking, the choosing—the creativity involved in picking—the feeling of having caught it, before anyone else does—the looking forward to it arriving, and the great feeling of power of being able to buy. I want everything except the object, which sticks its tongue out at me as I pull it from the box.

I read a book by a woman who wrote a blog about how she was not going to buy anything for an entire year. She was a smart woman, an Upper East Side mom. She was a television writer, and quite rich. She began with such bravado and certainty. And she lasted all of three months. She failed in front of everyone. She pretended her failure was no big deal.

Who among us will crack the code, and tell it to all the others? Tell the others how to have the feeling of consuming without buying anything?

*

Sara Cwynar looks for what there is to buy, but the meanings of the objects for sale—their meanings are entirely hers. The things she acquires gain value only because she picked them. She bought them, she arranged them, side-by-side with other things. She filmed them and showed them to us. She put them in a beautiful frame, the beautiful frame of her videos.

If any of the things she shows in her videos came to my house instead, they would not give me the same feeling that they give me there in her videos. They are beautiful because they are hers, and not mine. Because she is beautiful, and I am not. Because her life is beautiful, and mine is not. This is what it all comes down to. Whenever anything becomes mine, it becomes like me. And what is me but this chaos, this meaninglessness, this sloppiness and imperfection. She might be all those things for herself, too, but because she has put herself into her beautiful art, she is not that for me. She is like her beautiful art: finished, finite, ordered, edited, shot, selected, meaningful—and everything she touches in those videos has meaning and orderliness, too.

*

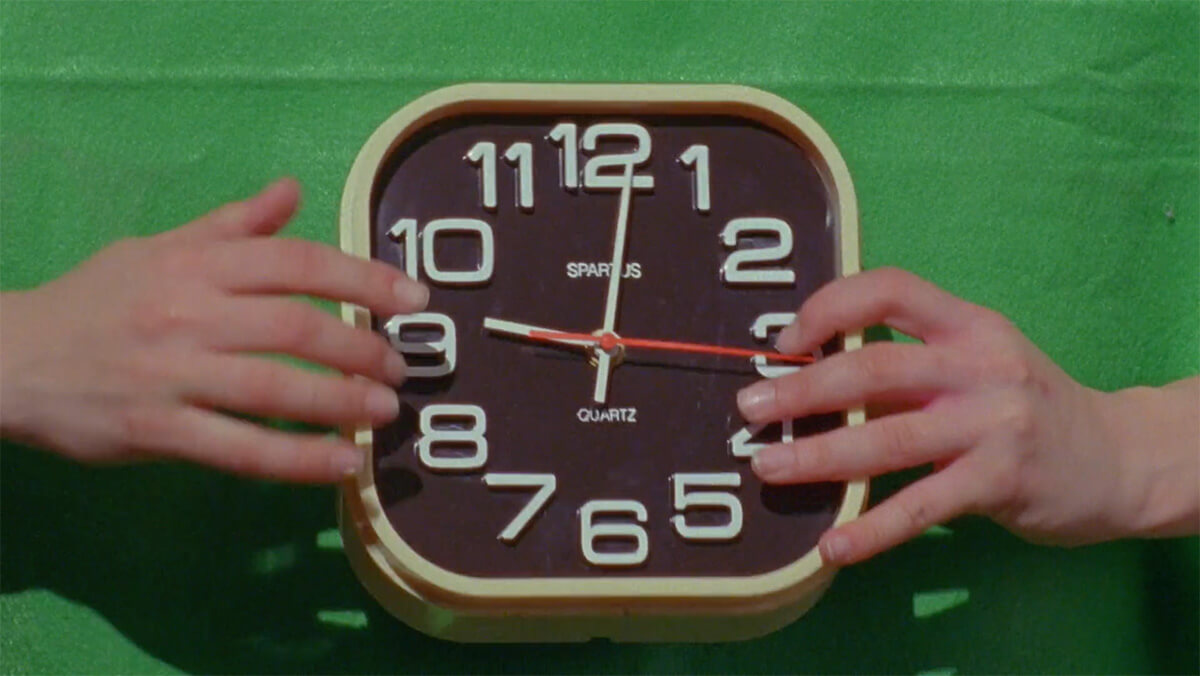

Her films are delicious. I want my life to be the color of her films, and for my days to be arranged by the same hands that move the face on her clock to 8:20. I want her face to be my face, and for her boyfriend to have once been mine. I want the bed I am lying in to be her bed, which is tinted red by a red gel over the lights. I want to buy little jewelry boxes, too, and to not be able to sleep from looking sideways at every page on eBay. I want to wear her perfect clothes, that are baggy and interesting colors, and don’t look like they cost much. I want her pretty face and big eyes, and her long hair and her sneakers. I want even the sneakers that she wears in the video that she says she does not like. I want to have a studio with a floor full of things that I arrange, and to work every day with my hands, arranging. I want to make the videos she made, and to smile, like she does, at the man behind the camera while lying in a bed. I want all of that as much as I want whatever it is I bought on eBay, or Amazon, or etsy, today or the day before yesterday.

I can’t have her things, her face, her life. But I can have it, too. I can look at her videos all I want. But I don’t want to look at them! I want to eat them. I don’t even want to eat them—I want her videos to be my life. I know it’s no more her life, those seven-minute videos, than “partying on a back deck in the summer with bikini-clad women and muscly men” is the life of any of the actors in the beer ad. Yet this has nothing to do with the actors in a beer ad, because she made it. She made those videos! So even if it’s not her external life, it is her internal life. If I watched her videos a hundred times, perhaps I could make her world mine. That would be a way of eating it. And yet I know I won’t. I won’t watch her videos a hundred times. I want her world to be mine much more easily than that. I want her world to be mine by putting it in a cart on the internet, and buying it, and having it arrive at my door, and unpacking it, and knowing it’s mine and no one else’s. All the things of the world I want—I am too impatient to slowly imbibe them. I want to purchase them and have them in my home, and go to bed and be done. The only way to imbibe art, to imbibe anything, is—as the voice in her video said, to look at one thing at a time—just look, slowly, as if coming in from the side...

Am I still capable of looking slowly, as if coming in from the side?

Or have I ruined myself? Can I now only buy?

*

How can I make my stuff meaningful enough for myself that I never have to buy anything anymore? Must I arrange it all better in my house, the way she arranges things in front of the camera, moving them around? Yes. I won’t buy anything anymore. I’ll just move what I have, around. I’ll jump right to that phase of the artistic process: not the ordering from eBay phase of Sara’s artistic process, or my own sickly consumerism—but the organizing on the ground phase of the artistic process. Proceed as though you have all the things. You probably do have all the things. And you have thrown so many things out!

*

I’d really never thought before of rearranging the things I have—or considered that an artist edits, arranges and puts things in the right place, a place that gives them beauty and meaning. When something comes to my doorstep, it is just a thing, like when words fall onto my page, they are just words, fallen onto whiteness. It is the arrangement and placement and all of the editing that charges them with meaning: it is the working with the words that make them mine. So might it be with the things that come to me in the mail, that I ordered mindlessly on eBay: by working with them, arranging them, forever and for their lifespans, putting them here, moving them there, tending to them, combining them—it might be doing this that will change them from the inert thing that arrives at my door, which I always feel a kind of disappointment at receiving, into something charged, more like art, charged with my being, with meaning and purpose and feeling. That would finally make them mine, and would endow them with something greater than the banality of possession.

Then I will keep my things in constant motion, like Sara does in her videos, always moving objects around, first here, then there, so they are constantly changing meaning, their relationships always changing. When she removes something from a scene, it is like she is swiping it from her phone; removing one object, or placing it somewhere new. Swiping is creating, it’s a kind of magic, it makes things appear and disappear. But swipe not just to put something in your cart. The swiping must continue once the object is yours. The ever-swiping makes you an artist. The swiping gives it meaning.

*

Sara Cwynar’s narrator says, “My skin falls but rose gold doesn’t change.”

Rose gold is an ideal, perfection. Rose gold is nothing. It is just two words. It cannot decay or change.

Rose gold cannot be what she loves. The things she likes to collect are jewelry boxes that fade, and are beautiful for their fading. They represent an eternal color: the fading color of time. What is the color of time? It is the color of fading. It colors every other color.

We should see the things we own as having more and more value, as their color mixes with the color of time, as the things we own become time. Part object, and part time.

*

In Rose Gold we see all these fingers, swiping, observed from behind a glass, these little gestures, so delicate, so small. The narrator says of life now—the life we live on our iPhones: Reality is touched not with direct confidence but with fingertips that are immediately withdrawn. That is how we go at consuming—we are tentative and we are scared. We consume not with direct confidence, but with fingertips that are immediately withdrawn. She moves the objects in her videos, always moving them about. She makes art not with direct confidence, but with fingertips that are immediately withdrawn. The more I write this phrase, the more beautiful it becomes. Is that what life is—not a path proceeded along with direct confidence, but with fingertips that are immediately withdrawn? Is that how we love now? Not with direct confidence, but with fingertips that are immediately withdrawn?

*

I emailed Dorothea Lasky, saying that although I buy things for my home, for my body, I actually don’t collect things, the way she does—the way her shrine revealed. I buy things but I also throw things out, suddenly and with great need. That is my great compulsion. I take great pleasuring in throwing things out. In throwing out, suddenly, all the things I have bought. Is it because they disgust me? Do they threaten to hold me down, so that I can no longer shift and move, like the objects on the floor of Sara Cwynar’s studio? There are so many clothing items, objects I look back on, and wonder why I threw them out. I feel ashamed because my reason was so spontaneous and emotional: it was in my house and, irritated one day, I felt it must be gone.

I had told Dorothea that the photograph of her desk seemed like an altar or a shrine. She said she does think of her collection as a shrine. She wrote, “The accumulation of these things in a particular placement is a type of prayer that to me resists the idea that there is a way to do it. Like oh yellow cup, of course put that in the cupboard, duh! But it’s like, NO, I want to put it HERE.”

I read that and thought, I have no shrine. I have no type of prayer. I buy compulsively and I throw out like a bulimic—I’m a bulimic with my things.

She said, “I think your instinct to not have things, to throw them out, feels the same as my compulsion to make my shrines. There is a severe need in both instincts to control what we do—and not have it be because some other force thought it should be some way. Maybe this is about being an artist, too. It’s about, my life’s purpose is to do this to things. And things can be words. I mean, of course they are.”

This essay is adapted from a talk for Oakville Galleries’ Authors on Art series, presented in partnership with the Oakville Public Library on April 11th, 2018.