Stephen Varble: Now More Than Ever

Bob Nickas

October 22, 2018

A chauffeured Rolls Royce glides glacially to the curb in front of the Chemical Bank at New York’s Sheridan Square. The uniformed driver, out in an instant, holds open the passenger door. Rather than a well-heeled person to which such a car would belong, a more hallucinatory sight will emerge, equally glamorous and ridiculous. Two legs appear, only one of which has a shoe. The full length of the body gradually appears, improbably covered in netting and not much else, the entwined nets adorned with crumpled bills. What seem to be bare breasts droop from the chest of a figure of otherwise unidentifiable gender, further confused by a toy fighter jet, poised for takeoff, at crotch level. While no words are spoken, a cartoon speech bubble overhead proclaims, cheerily but with a disgruntled undertow: Even Though You May Be Forged, Chemical Still Banks Best!

Passersby on the sidewalk, taking a safe step back, surely wonder as this spectacle unfolds, What planet are we on? What chemicals has this person ingested? Once inside, customers on line and employees double- and triple-take. Up close, the bills in the netting are revealed to be money from the Monopoly board game, whose winners acquire real estate and wealth, whose losers end up in jail or bankrupt. As we may recall from younger days, being punished in play: “Do not pass Go. Do not collect $200.”

Now in front of the teller’s windows, this delirious embodiment of capitalism and its discontents has been victimized. A check has been forged, from which a plane ticket was bought, and an appeal has been made to have the funds restored—which the bank has been unwilling to do. Seated at the manager’s desk to plead the case, this innocent victim of check fraud, although outrageously costumed, behaves as if it was the most everyday thing to wear. His neatly trimmed mustache and beard register as male. All else is simply … beyond. (Has the manager, a meek, bespectacled wisp of a man, even noticed that the breasts are condoms filled with a sanguine liquid?) Told that nothing can be done, the victim rises silently, positions himself center stage, and punctures his condom breasts with a pen. Cow’s blood spurts forth, into which the pen is dipped as he proceeds to write checks for None Million Dollars. Bank customers break into cheers and applause.1

*

It’s 1976, America’s Bicentennial, and the perpetrator of this guerrilla performance is Stephen Varble. You’ve probably never heard of him, and why would you? Though his presence was indelibly felt at the time in the New York art world—so much smaller then, a little village where practically everyone knew everyone else—he was active for a brief five years, between 1973 and 1977. This was a period well ahead of the internet and social media, before artists of a certain ambition kept publicists on retainer, as well as reaped the abundant free publicity of a paparazzi public, phones-in-hand, ever ready to film and photograph any event that stops traffic, as Varble did so often and effortlessly. (His favored stage, it’s been said, was the street.)

Today, Stephen Varble would be immediately notorious, slid down Youtube as if it were a waterpark slide, commissioned to present new work at Performa, seated next to Marina Abramovic at the gala dinner for the Met’s Costume Institute. This, of course, would be an even more improbable parallel universe than the one in which that Rolls was parallel parked. Steven Varble today would turn down that commission—How dare you!—would crash the Met Gala, stare down Abramovic, and swat away the iPhones aimed in his direction. (Always accompanied by his own personal photographer, there are evocative pictures of Varble taken by Jimmy DeSana, Peter Hujar, and Jack Mitchell.)

Imagining his militant reluctance may be a matter of conjecture, but it’s based on the terms of refusal and contradiction by which Varble himself conducted his anti-career. For his sole appearance in a commercial art gallery, on tony 57th Street no less, he priced his works far beyond what anyone sane was willing to pay, only offered reproductions of his drawings, leaving the gallery with little chance to profit from the show. Varble, having thrown down an absurdist gauntlet, might as well have said, fifteen years before it was born, Take that, institutional critique!

Varble, currently the subject of a retrospective at the Leslie-Lohman Museum, Rubbish and Dreams, organized by David J. Getsy, is ripe for rediscovery. He was a post-‘60s artist marked by the second half of that turbulent decade’s antagonism toward institutions and the market. Against a backdrop of the war in Vietnam, the women’s movement, gay liberation and black power—a roiling up of emotions that made the times equally visceral and heady—many artists saw themselves on the front lines and would never retreat. In his press release for the Chemical Bank Protest, Varble refers to Sheridan Square as located “in the heart of Manhattan’s gay ghetto.” This is particularly notable, as the bank was a short block from the Stonewall Inn, site of the 1969 riot that ushered in the fight for gay rights. Varble’s reference suggests, seven years later, that he was already post-Stonewall, and provocatively so. Anyone who made such an unbound spectacle of himself would have nothing to do with assimilation and containment.

Early on, Varble had been “under the influence” of filmmaker/performer/iconoclast Jack Smith, who so despised systems of artistic and social control that he acidly turned capitalism into clapitalism, as if the overly complacent deserved only the applause of a sexually transmitted disease. In a 1976 letter-to-the-editor plea, Varble all but calls for an art strike (shades of infamous dropout Lee Lozano, circa late ‘60s, and the Marxist-dandy art critic Gregory Battcock, one of Varble’s supporters2), complaining that artists won’t band together to fight against the lack of support for their work. Rallying his fellow artists by wickedly mocking curators—while unknowingly anticipating the culture wars of the ‘90s—he wrote:

“Only museums … composed primarily of multilingual janitors … seem to have the wherewithal to grovel in any kind of unison for government funds.”

Taking to the streets, appearing before a non-art audience, always caught unaware, without knowing who on earth he was, Varble’s self-proclaimed “gutter art” was an indictment of high culture. In the mid-‘70s, he performed—both invited and uninvited—at Tiffany’s and the Halston boutique; crashed the movie premiere for Ken Russell’s Tommy, posing with an unfazed Tina Turner, pretending to chew on his chicken bone tiara; descended upon the launch for Fashion As Fantasy at the Rizzoli Bookstore in his fantastic-priapic Piggy Bank Dress; strode into the opening of Diana Vreeland’s American Women of Style exhibition at the Met wearing rhinestone-covered baseball gloves and an oversized football on his head; and audaciously upstaged German artist Joseph Beuys, the master shaman/showman, at his own New York gallery opening—Varble appearing in his most ingeniously beautiful creation, an Elizabethan dress made of egg crates and tulle. In a Greg Day photograph, Varble could be seen as a human marionette framed in a Dutch Old Master painting.

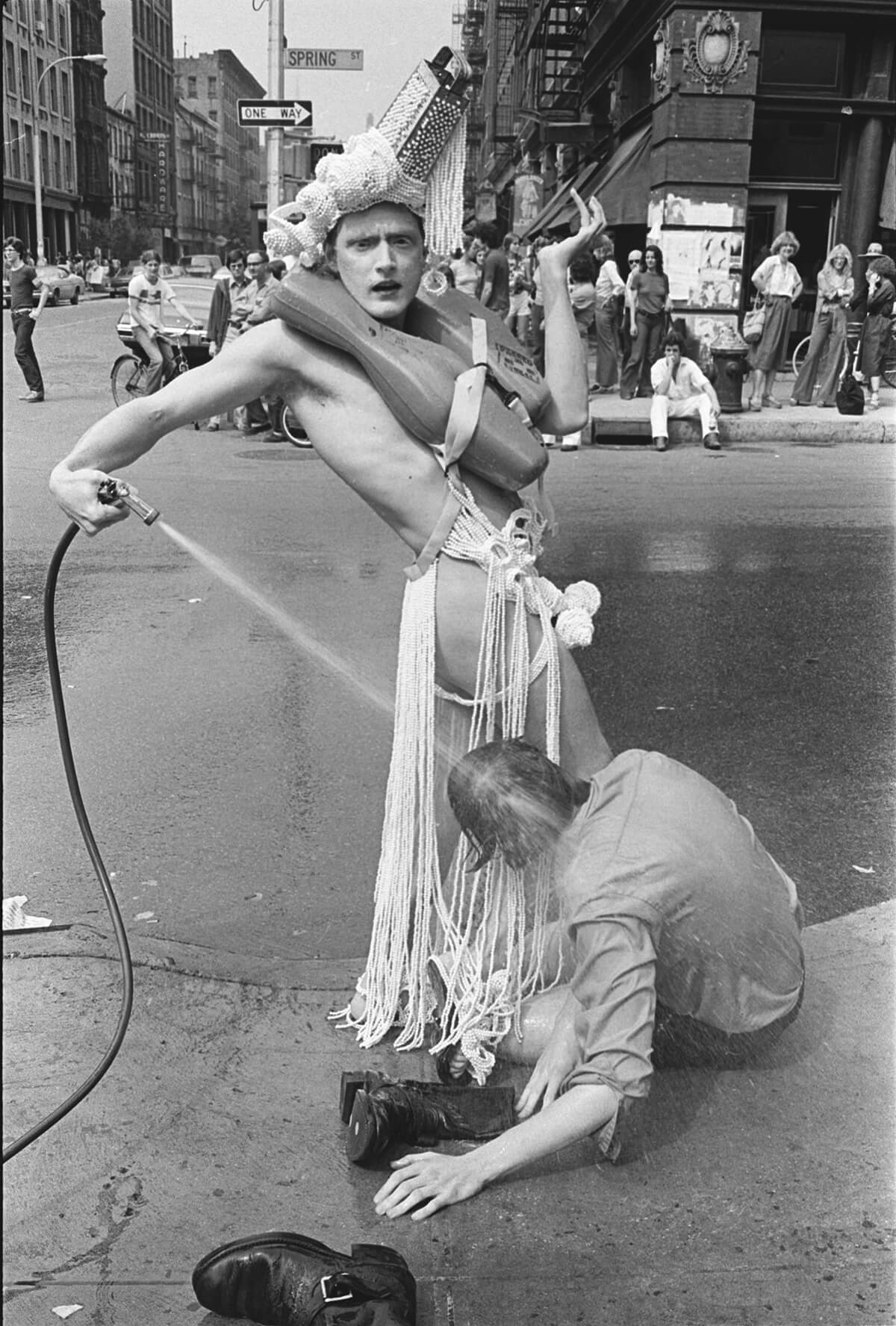

It’s here we can appreciate the finely considered negotiation between art history, a theater of the ridiculous, and a poignant performance of the altered self (with a dose, or overdose, of rollicking humor) against the entertainment-industrial complex of our time, particularly in its increasingly mainstream “deviance”—Wigstock, RuPaul’s Drag Race, et al. One of the standouts in the Leslie-Lohman show is a recreation, by Vincent Tiley, of Varble’s Pearl Dress, originally conceived in 1975. Emblematic of the artist’s “neo-savage costumes” and “garbage attire” (his own terms), long strands of fake pearls barely cover a naked body topped by the pop-perverse addition of a bright orange life preserver, covering his, or her, or their chest.

The subtitle that Getsy gave the show, The Genderqueer Performance Art of Stephen Varble, acknowledges the intentional, fluid confusion with which this artist so actively engaged, enabling him to provoke the public in broad daylight in a way usually reserved for clubs and a nocturnal shadow-world. This sort of exhibitionism was most publicly acceptable in what was then New York’s more outrageous “what-the-fuck-was-that?” Halloween parade, an event of free but fleeting permission. Did Stephen Varble ever ask anyone’s permission to do anything? Doubtful.

He came from a generation that understood you can never risk the chance of being excluded, shut down, told no—because you had been. In this respect, in terms of style and sensibility, of a keenly clear-eyed derangement, he has much in common with the Cockettes, the post-hippie/pre-glam San Francisco performance collective. Their legend preceded them, and they only appeared once in New York (disastrously, it turned out, for their particular brand of anarchic lunacy apparently did not travel well). We don’t know whether Varble was in attendance, and they were probably unaware of his work.

Varble is very much a precursor to the great Leigh Bowery, who ruled London for a decade beginning in the early ‘80s, presiding over his nightclub Taboo, with his jaw-dropping sculptural costumes and demented live appearances. (His astounding birth-performance at the ‘93 Wigstock—a must-see on Youtube—came nearly ten years after Varble died of AIDS-related complications in 1984.) Varble’s total irreverence is no more evident than in his willingness to “cross party lines,” as he did when he wore his Suit of Armor, constructed with gold VO labels from Seagram’s boxes, to both the 1975 Easter Parade and to West Village leather bars! He was an equal opportunity offender, rubbing up against conformity in all forms.

Being little-known today is not only a matter of Varble’s untimely death, nor his distaste for careerism and the market. Nor is it a result of being from a time before every single thing is documented within an inch of its life, and ours. He, as other artists of his generation—again, Lee Lozano comes readily to mind—stepped away from the stages they inhabited or invented, whether the gallery or the street.

Varble spent the last years of his life immersed in his apartment, which he turned into a studio-installation, laboring over what has been described as an epic, unfinished video, Journey to the Sun (1978-83). An extended segment of its four hours is on view at Leslie-Lohman. The only other extant footage of Varble’s work comes from ten years prior, and brings us full circle: a glitchy black-and-white video shot at New York’s venerable off-off Broadway theater La MaMa, where his play Silent Prayer was staged in 1973. In a note written in advance of the production, he describes the play as:

“concern[ing] itself with the extraordinary, indeed miraculous faith of a Vietnam veteran who has returned home completely paralyzed, an invalid. He is surrounded by a deranged family in a desolate yet strangely peaceful Montana landscape. As he sits in his wheelchair, day after day, praying silently, he achieves a kind of holy ecstasy. He is visited by angels. Thus, the play brings into focus the powers of the human spirit.”

As we connect ‘73 and ‘83, the first stirrings of the artist Varble would become entwined with the last he would offer, his vision of the play serves remarkably as his own uncannily prescient epitaph.

- This narrative is based on a series of photos taken by Greg Day during the Chemical Bank Protest, which can be scrolled through on an iPad in the exhibition, augmented by Varble's press release, and other accompanying text, likely derived from first-hand account. Some poetic license has been taken.

- Working as Gregory Battcock’s college T.A. in the late ‘70s, I was first introduced to, and became immediately enamored of Stephen Varble’s art.