Brave Noo World

Fiona Alison Duncan

October 8, 2018

Frogtown is a basin of a neighborhood between Elysian Park, Silver Lake, and the Los Angeles River. On a map, the area is shaped like the top lip of Man Ray’s “The Lovers.” Also called Elysian Valley, though I’ve never heard anyone call it that, Frogtown was supposedly once home to the tiny Western Toad, some of which were smaller than pencil erasers, and that’s why where I live is called Frogtown.

If my block is representative of the lot, Frogtown should really be called Cattown. Though that could be true for a lot of Los Angeles. Strays breed like wildfire in L.A. Exact estimates vary, but they’re all in the low millions. Add to that another million-plus registered feline pets, and we’re looking at one cat per two or three people in the County.

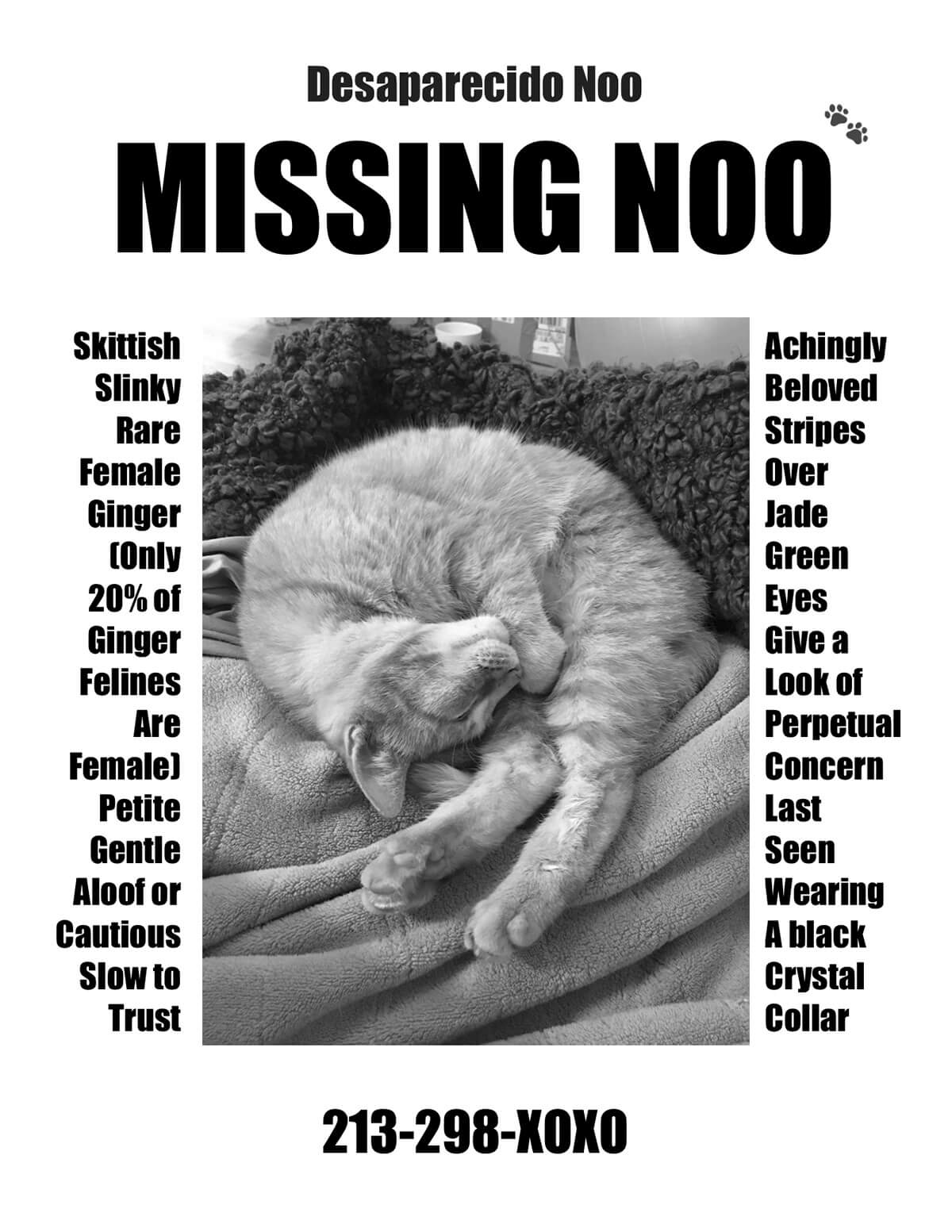

This August, after being away for four weeks, I returned to Frogtown to find that my cat, Noo, was missing. I’d first left Noo, an indoor-outdoor ginger rescue, under the care of Saoirse Flowers, a known cat whisperer and trusted friend, and then, when Saoirse decided he also wanted to vacate L.A., Noo defaulted into the care of my roommate Kyle. The day I was to return to Los Angeles and to Noo (from paying work and a pup of a boyfriend in New York), I tried sending my cat psychic messages: “I’m coming, my baby!” When, after a long-delayed flight, I walked into my room at 3 a.m., there was no Noo.

Noo is short for Noosphere, a philosophical term meaning the realm of human thought. It’s related to “the Anthropocene,”1 an anthropocentric term referring our current geological age on Earth. Following the Pleistocene (roughly, the Ice Age) and the Holocene (the warm period after, which includes all written human histories), the Anthropocene is a proposed era (start date debatable) wherein humankind is definitely changing Earth. Changes includes anthropogenic climate change, increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and animal extinctions.

When I tried calling my cat Noosphere, she stared at me like I used to when my professorial parents spoke to me in a vocabulary I couldn’t have understood at seven. “Like what are you, an idiot?! Of course I don’t know what sophomoric means yet, Dad.” I shortened her name to Noo, but didn’t stop anthropomorphizing my cat. I used to joke that, “Noo is a lesbian separatist,” because when I hosted certain types of bedroom guests, “she gives me a death stare,” and if the boys stayed long enough, she’d leave, for days. When Noo wasn’t home when I returned from New York, I wondered if she wasn’t teaching me a lesson for leaving. “Or maybe she wants to help my assignments!”

I was right then researching companion species and holistic Earthly kinship, the work of Donna J. Haraway, in preparation of interviewing her on the occasion of Fabrizio Terranova’s feature documentary about her, Story Telling For Earthly Survival. And I was scheduled to write this portrait of Los Angeles through its animal life. I initially imagined a Pixar movie of sorts. It would start with a natural disaster. A drought-season fire or earthquake hits Los Angeles, and a number of its animals are displaced. House pets struggle to survive without their doting owners. Coyotes feast. Zoo animals, suddenly free, suffer from mounting confusions: dysphoria, agoraphobia, derealization. Monkeys try to swing from power lines and are electrocuted. And giraffes hate the feeling of walking on concrete; they slip, like girls in too high heels on Hollywood Boulevard’s stars.

Flocks of wild green parrots (who’re real; they fly L.A.’s East Side, rumored to have escaped from pet stores and owners during 1961’s Bel Air brush fire, or from Van Nuys’ Busch Gardens amusement park when it closed in 1979) serve as rescue volunteers, guiding the newly freed zoo creatures, and pampered pets, to safety and good eats. As for the famous mountain lions of the Santa Monica Mountains—the quake or fire will have made a natural bridge, so the current, fifty-million-dollar initiative to make one will no longer be needed, and these beautiful golden pumas, who face extinction due to inbreeding and human development, can cross what was once ten lanes of freeway into the Santa Susana Mountains and the Los Padres National Forest, and prosper.

Then I learned that Mike Mills is already making a feature film about the mountain lions, a follow-up to his art book Together: Wildlife Corridors in Los Angeles.

*

I can’t afford a car, so I’ve an ambitious experience of Los Angeles. I walk, bike, bus, and rideshare. In no other city does every dog in a yard, so unused to pedestrians, bark when I walk by. I often meet packs of feral cats. I’ve yet to see a frog, or toad. It seems too dry. Chickens are common though. As far as rodents go, I’ve squealed past more opossums than rats. On Hollywood hikes, you have to snake around snakes and agents alike. Coyotes are to be avoided, or warded off with noise. And they’re no longer just in the hills. Just last night, I saw a band of coyotes stalking our lowland Frogtown street. “They eat cats,” my neighbor warned. “Lock yours inside.”

I’d been home for two days and Noo was still missing. On my second morning back, my roommate Kyle came out of his room saying: “It smells like something died...” I’d noticed it too, but I thought maybe one of the roommates had squirreled trash around the house. I was pissed, but repressed it. Now I really let myself smell it. Kyle and I followed the stench to the back of the house. I was already mildly hyperventilating, because you know, Noo was missing.

On the backside of the house, we found a hole that lead to a crawl space. I got on my hands and knees, in the dirt, held my iPhone flashlight up to the hole, and looked as clear as I could into the dark. My glasses were filthy, and the prescription is out of date, so it was hard to see, but I swore I saw a little body with cat-like-ears on its backside, one stiff paw reaching towards Heaven. Its fur was sandy, light; like Noo’s in the dark. I burst into tears.

The scene called the full house to attention—all four roommates, and one of their boyfriends, were drawn into the drama. After conferring for a while on what to do, eventually, one of us drove (since they never answer their phone or emails) to the leasing company (a corporate, gentrifying organization) for aid; one of us had to go to work; Kyle said he was going to get gloves to help move the dead animal; and I was left alone. I called the Los Angeles Department of Sanitation and booked a Dead Animal Removal. It’s a free service, they respond within 24 hours, but won’t come far onto your property, so it was up to us to move the dead body to the street.

The next thing I knew I was awoken from a grief nap to the sounds of Timothy, a young man from the leasing company, rustling behind the house. He’d been sent without a real brief and with no helpful supplies: no gloves or mask, not even a garbage bag. When Kyle came back shortly after, he was also without gloves. So Timothy had to excavate the dead animal in a very unsanitary fashion, and it was HUGE. Kyle said, “There’s no way it’s Noo.”

But this creature’s tail looked like hers—Noo has a signature tail. The rest of the body was yes, too big, and too pale. But maybe, I thought, a dead body, under high heat, will bloat this much? And pale? My dad, a science-mind, and former farm kid, said maybe.

*

When I lived in Koreatown, the only animals I saw, besides neighbors’ pets, were insects, mostly German cockroaches, who basically run The Gaylord apartments. And birds. There was a mocking bird that mimicked the car alarms outside my bedroom window on Mariposa, a.k.a. “Butterfly,” Avenue. Once a sparrow landed on my knee for the full duration of my coffee in a sliver of a park. In MacArthur Park, there were flocks of Canada geese, seagulls, and pigeons. The park is so covered in bird shit, if Jackson Pollock had seen it, he’d be more embarrassed about his drip paintings than he probably unconsciously was.

And of course, each and every day, the sky above Ktown and MacArthur continues to thud with what Ice Cube called Ghetto Birds: police helicopters, which according to Mike Davis, were introduced in response to 1965’s Watts Riots, a neighborhood rebellion in protest of police brutality. “LAPD helicopters—” Davis wrote in his 1990 City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles:

...maintain an average nineteen-hour-per-day vigil over ‘high crime areas,’ tactically coordinated to patrol car forces... To facilitate ground-air synchronization, thousands of residential rooftops have been painted with identifying street numbers, transforming the aerial view of the city into a huge police grid.

While South and Central L.A. are surveilled by mechanical flight, affluent neighborhoods in Los Angeles have recently seen the introduction of a grounded Bird. Founded by Travis VanderZanden, a former executive at Lyft and Uber, Bird is an app-based electric scooter rideshare business. The scooters can be picked up wherever you find one, and left wherever you want, within a GPS-designated area. So far, Birds are only on the Westside, in prosperous pockets like West Hollywood, Venice, and Santa Monica. You’re not supposed to ride them on sidewalks, but everyone does, because everyone drives in L.A., and so everyone knows how dangerous it is to travel on anything weighing less than 3,000 pounds.

But my favorite Los Angeles bird by far was Bob, a classically-coated male pigeon that artist Amalia Ulman purchased from a pollería in Vernon, an industrial city in the center of L.A. County. At this pollería, you could buy live doves, budgies, chicks, chickens, pigeons, fresh eggs, and feed for the birds. Bob was ten dollars. Ulman lived and made work with him for two years.

Bob became the star of memes, Picasso meets the New Yorker-style cartoons, a pin-up calendar, and a film. In the early work, Bob’s character was like Bill Watterson’s Hobbes to Ulman’s Calvin, a wise sidekick to her frantic protagonist. But while Calvin resisted school, Ulman’s protagonist was older, a burnt-out businesswoman with a square office in Downtown. There Bob would fly amidst whiteboards, clocks, calendars, and other custom work-hard paraphernalia.

At this year’s Armory Show in New York, Ulman installed a precise recreation of this office. On one of two computer monitors was her film, BOB LIFE. The film is structured by a voiceover: Bob, the pigeon, tells his origin story. He was a racing bird (pigeons are prized racers) with a wife (pigeons mate for life), when, in the midst of a race, an earthquake hit, and he became lost. Bob first lands in MacArthur Park to rest. Eventually, what he calls “a big hand” grabs, cages, and drives him to a cold place with more cages, where soon after a figure he calls “Idiot Lady Human” buys him. Idiot Lady Human is Amalia Ulman.

Bob narrates his experience living with her for two years. Humiliation. Isolation. Shame. His story is that of a prisoner. At times, Bob is hopeful, pumping his wings, so he’ll be ready to fly when finally free. Then there’s depression, lethargy, overeating. He writes poetry, reflects philosophically, and coos for his lost love. Then he gives up. Stockholm Syndrome. I don’t want to spoil the end.

Ulman’s story of Bob—as trapped by her self- or art-interested mania—reminds me of another artist’s perspective on pets. My pup of a boyfriend, Matthew Hilvers, was painting, while I was in New York with him, a large work with a side of text that said:

DOGS NEVER CONSENTED TO BEING OWNED A NEU COLONIAL WAY

Matthew doesn’t believe in owning dogs, but coos every time he sees one. (If it’s a Corgi, we have to stop to pet them.) The painting is a provocation, of course, and I’ve heard the argument before: Owning pets is akin to slavery, we dominate the animals with our assumed mastery, when really they should be free...

“No account of the appearance of dogs on earth,” Donna J. Haraway writes in The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, “goes unchallenged, and none goes unappropriated by its partisans.”

This is true of course for many histories, and currents. With contradictory human theories with varying proofs of what is and was, what are we to do? Even if we could come to some consensus on history and contemporary reality, what are we to do? What’s the right thing to do when: The bird is already in the cage? The cat is homeless but litter trained? When you know the land you live on, “America,” was stolen from native populations, who didn’t believe, like you, that land could or should be owned, but you still have to pay rent to a local landlord or worse: my commercial leasing agency? Humans are domesticated. Are we un-free like my boyfriend believes dogs to be? The other side of his painting reads:

SO. UM HA HA HA. HOW DID WE GET HERE? IDK MY GOD MY HEAD MY ♥. R WE NOT UM.

In The Companion Species Manifesto, Haraway writes that, in terms of understanding the history of the relationship between dogs and humans, she looks, “for ways of getting co-evolution and co-constitution without stripping the story of its brutalities as well as multiform beauties.” Later, she summons something like that 14th-century work of Christian mysticism, The Cloud of Unknowing, or like Joan Didion’s slogan: “Play It As It Lays.”

Haraway suggests that knowledge of “the intimate other”—whether human, animal or inanimate—is a permanent search. “Just who is at home,” she writes, “must permanently be in question. The recognition that one cannot know the other or self, but must ask in respect for all of time who and what are emerging in relationship, is the key. That is true for lovers, of whatever species.”

Love, for Haraway, is a way of knowing in unknowing, of recognizing without projecting or trying to control.

“Pierce that thick cloud of unknowing,” the anonymous mystic of Cloud writes, “with a sharp dart of longing love.”

I can’t help but think of the sharp dart as the wet tongue of my boyfriend in my ear, or of Noo when she decides that I’m worth grooming too.

*

The late L.A.-based artist Mike Kelley is still most famous for his stuffed animals, which he called “love objects.” He collected handmade stuffed toys, mostly animal-like, and stitched them together as wall pieces, or placed them under, on, and around blankets on the floor. This was the late eighties and early nineties, when in North America there was a moral panic around child molestation (born in 1987, some of my most vivid early memories are television specials about this; identification, fascination, and fear), so it’s not surprising that contemporary audiences interpreted Kelley’s “love objects” in relation to child abuse.

Kelley recognized and played with such audience projections—with the idea of projection. On a series of white panels, presented in 1990, he painted these handmade stuffed toys in a much larger scale. A wonky knit bunny, stretched as tall as me, looks like it could’ve inspired the psychotic rabbit in Donnie Darko. Kelley titled the works “Empathy Displacement,” and later explained this to artist John Miller in BOMB:

The empathy displacement has to do with how you empathize with a doll and the fact that the more you empathize with something the more you don’t see it for what it is because you see it as you. Blowing these images of dolls up to the human scale and having them so deadly rendered makes you more aware of the strangeness of the morphology, how it differs from you. If you saw that thing walking down the street you wouldn’t go near it, it becomes hard to project onto.

When I first moved to Los Angeles, I was enamored with the city’s declarations of love. The streets are littered with it: graffiti and advertising, often indistinguishable from one another, that read: I Love You. God Loves You. Got Love? Just Love. All you need is the right kind of love. Protect yo heart. Love love love love. Love Angeles. Ruben Rojas is responsible for a lot of the “love” around town. He paints rainbow affirmations on urban landscapes, including, recently, a set of murals at the Los Angeles Zoo. They were the last exhibit I saw there, on my guided tour.

I was driven around the property by Jacob Kowal, a young man who’d aspired to his position—working marketing for a zoo—since he was in in high school. (That’s another affirmation L.A. loves to repeat: Dream, Dreamer, Dreams Do Come True.) Jacob drove myself and Francie Klein, a docent in her 25th year with the zoo, around in a golf cart.

The last time I was in one of these was at the Brant Foundation. I was new to America then, on a beauty press assignment for a Canadian magazine, and innocently or ignorantly surprised that all the young help at the Foundation, dozens of these golf cart drivers, were handsome black and brown men in matching khaki trousers. There was a polo match; all the riders were white dudes. Stephanie Seymour wore blush pink Alaïa.

Francie Klein wore leopard print mules and a larger lion head pendant. I’d been reading John Berger on animals. Berger writes about how zoos and stuffed toy animals came to prominence as living animals were disappearing from daily life in the West. When the first zoos were opening in Paris (1793), London (1828), and Berlin (1844), Berger writes:

The capturing of the animals was a symbolic representation of the conquest of all distant and erotic lands. ‘Explorers’ proved their patriotism by sending home a tiger or an elephant. The gift of an exotic animal to the metropolitan zoo became a token in subservient diplomatic relations.

This Los Angeles Zoo opened in 1966.2 Most of its residents were born into captivity. Some of the plants and animals on the property, Francie Klein also told me, were confiscated by the Department of Fish and Wildlife; illegal to keep personally in this country, they were then placed here. A majority of the zoo’s animal species, I learned, are at risk of extinction in the wild. All the peacocks in the place are named Kevin, and they’re all cocks. “We were overrun by the species at one point,” Klein explained. “Now we only have males.” In addition to the enclosed animals, the zoo is frequented by local wildlife, among them squirrels, raccoons, skunks, coyotes, and rattlesnakes, who’re drawn to the place by its abundant rodents. The zoo can’t use poison, for obvious reasons.

“Nature’s not nice,” Klein told me. We were standing in front of a small display of two elderly meerkats who had to be separated from the rest of the meerkat colony when its fitter members started harassing them. “Social animals can be very mean,” she continued. “There’s always hierarchy reorganization.” It’s unlikely these kats would’ve gotten so old outside of captivity, where they’re supervised, fed, and medically treated. “Nature doesn’t do a lot of old,” Klein, a grandmother, repeated.

Certain animal rights activists call for the dissolution of zoos, for captive animals to be moved into “sanctuaries,” which Klein noted, “is a beautiful word, but just that—a word.” Animal-entertainment breeding facilities often market themselves as sanctuaries. And legitimate facilities, like many pure-hearted charities, can be underfunded. At least zoos can generate revenue through admission fees to pour back into research, provisions, and care.

“We’re all here because we love animals,” Klein insisted. She’s saddened by critiques that don’t account for this.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my three last years in Los Angeles, it’s that proclamations of “love” are often party to abuse. It’s a beautiful word. I had a great time at the zoo. Ditto when, at a birthday party in woody Pasadena a few days later, a hired clown gave a “safari performance” that involved taking 20-odd animals out of tiny cages. Rodents, insects, lizards, birds, little mammals like rabbits, and snakes. The hedgehogs were so cute! A Rosa Boa wrapped around my hand was like jewelry and a massage. Just like at the zoo, I recognized the lameness and injustice of these animals’ enslavement, but was awed giddy by the opportunity to look upon and touch them. I wondered if this was how my first Los Angeles boyfriend felt in relation to me.

A charismatic serial adulterer, his schtick was telling several young women—concurrently, not that we knew—that he loved us so much, and that’s why he was possessive, prone to anger; why we shouldn’t dress, or talk, or use social media like that. Our lovability and sexuality threatened him; he sought to control it, and we liked it, for a bit. It was after researching local cult leaders like Charles Manson—recognizing how my boyfriend employed the same seductive, manipulative language—that I adopted foster kitty Noo. She had the same green eyes as him, but didn’t seem to want or “need” me, at all.

*

“I should’ve putta camera on her!” I wailed at my father on the phone, staring at the dead cat in front of me, trying to determine if it was Noo or not.

“Should I have put a camera on you?” he replied.

Despite holding Haraway’s ideals of loving the mystery of the other, I was projecting wild movies into the void of Noo. In one, Noo heard my psychic calls of homecoming, and seeking to teach me a lesson, sourced a lookalike, killed it, and placed it under the house, then found a shaded perch from which she could watch the ensuing action. Noo wanted revenge, or equality: for me to know what it feels like not to know where your beloved went. “That bed’s cold without me isn’t it, bitch?” she laughed in a self-congratulatory purr.

In reality, if Noo were still alive, I recognized that she probably smelled her dead relative before we visual-cortex-overstimulated and so otherwise-desensitized humans could, and left because it smelled disgusting. Noo is highly sensitive and intuitive. She hates loud noises (parties), frantic behavior (stress), and really, anything ungodly, like the boys I used to bring home. She was the only cat of five on our property to notice the fleas when they infested, and when I gave her the flea treatment, Noo somehow knew to curl up by a water source (the toilet bowl) so the pests would jump off her skin and into it.

In the days that followed the discovery of the dead cat, I dragged myself to non-cancellable commitments; called friends and family for comfort; felt guilty, ashamed, hopeful, furious, and sad; and made plans to make a “Missing Noo” flyer with my friend Chloe. Meanwhile, the Department of Sanitation had come and gone without taking the rotting body, because it apparently wasn’t in an obvious enough container. And so, whenever the wind blew easterly, the scent of decomposing feline flowed through the house.

An hour into a public transit journey, I watched an ant climb up my stomach on the subway. I wondered if the ant originated from my home, where there are many, or how else it had ended up on the Expo Line to Santa Monica. I thought about visiting the Ice Age fossil lab at the La Brea Tar Pits but felt too depressed. I thought about Jack Goldstein, who was also depressed, dropping out of the art world to live in a trailer in San Bernardino with his dogs. I could only perceive the dark side of Los Angeles: cigarettes flicked down city drains, killing dolphins; the PETA Empathy Center and their salacious displays of animal torture; the beach littered with dozens of dead seagulls that artist Sojourner Truth Parsons and I stumbled upon last year; the two turtles who float in the pond at the top of Ernest E. Debs park, and how they always remind me of that news story of two young women who were decapitated up there.

And then there was Hollywood. None of the film industry’s animal trainer, animal actor, animal rental businesses would return my calls. I should’ve lied, that’s the basis of Hollywood; said I was a producer, not a writer; but I’ve been trying not to act even modestly wrong, so that I can at least know that what’s wrong in my life isn’t my fault.

Two things helped: Alake Shilling’s fucked-up, beautiful sculptures of butterflies, ladybugs, teddy bears, and frogs. And Animal Shelter, a journal of art, sex, and literature edited by Hedi El Kholti. I dragged the first issue (2008) around town with me and a few people at openings noted, “That’s a good one.”

My mental hygiene was improving. I felt elated when I realized that I’d never noticed that Animal Shelter the journal might refer to animal shelters, as in where Noo was once caged and named Pumpkin—and where she might be now. I love that about language, that you can give familiar words a new context, and if that new context is strong enough, you can transform words, and with them (add an “L” for Love!), worlds. There was hope.

I once dog-sat a rescue named Quake. A straggly, short-legged mutt, he was found in the rubble of an earthquake. This dog could walk himself. We’d walk Central L.A. without a leash, and Quake would never run off. He’d walk precisely beside me, or a few strides ahead. If I lagged behind, he’d stop, turn around, and wait. When I asked this dog’s… I don’t want to say owner, master, or mother... Can we think of a new word for the primary person in a dog’s life? When I asked this dog’s... person how she trained Quake to walk so responsibly, she replied, “Oh, all my dogs have walked like this. I just let them.” I still don’t fully understand this, but I relate it to the risk of freedom that I try to embrace in caring for myself and others, including this indoor-outdoor feline rescue. I can offer the best home that I can, but she’s free to do as she chooses. She’s probably not even named Noo.

*

On my fifth morning back, the cat came back. I awoke at 7 a.m. to Noo staring at me, her luminous fur, her sparkling jade eyes looking better than ever.

- I always felt queasy about the idea of the Anthropocene. Not because I don’t believe climate change is real, but because of those who repeatedly summoned the word. They tend to be men with superiority complexes, spoken claims to righteousness? Though I very much appreciate the implication of responsibility (human industry’s made a mess that we should clean up), it seems to me egoistic, and false, and very Western, and Patriarchal, to erect man/humans as the defining force of our age, as if human history hasn’t proven how little we consistently know about anything, and as if Gaia isn’t. So I’ve been delighted to read Donna J. Haraway critiquing the term, both for its posturing of human exceptionalism, imagining that we are separate from the Earth and its immeasurable lifeforms, not of it, and them; and for the pragmatic reason that it’s not bringing communities together, to work to live to change. Haraway proposes that we situate ourselves within complex histories, using the term “Capitalocene,” for instance, to think about what that ideology and force of production has unearthed, as well as the term “Chthulucene,” to situate us on Earth. I like the term “Chthulucene,” because, in being ridiculous (summoning H.P. Lovecraft), it hints at the truth that all human terms for phenomena, that language is, ridiculous. “Chthulu” comes from “chthonic,” the underworld; I think of soil, and the plants in my yard, and the vital side of them, their root systems, that I can’t see without risking killing them. I think of the mystery of life, and how my summer sweat, which both Noo and my boyfriend love to curl into: my armpits, smells like sweet fresh compost and old books. I think of worms, ants, bacteria, whales, plankton, pets, and many other compelling creatures that risk decentering mankind from itself.

- The Griffith Park Zoo, now known as the “Old Los Angeles” zoo opened in 1912 with 15 animals. It closed when the current one opened.