Of the Fait Accompli

Gary Indiana

March 27, 2017

Thursday

Trisha Brown died this week. Bob Silvers died this week. (Why am I calling him “Bob”? I didn't know him at all. Robert Silvers, then.) David Rockefeller died this week. What did they have in common? Each has a place on a mental map of New York—the good New York of former times, one could say, vestiges of which mainly survive in survivors of those former times. Even Rockefeller, since the Rockefellers infused a lot of financial energy into the cultural landscape of the city. “Rockefeller Republicans” were secular cultural liberals interested in making money, not crackpot ideologues obsessed with making other people's lives miserable, as today's Republicans so clearly are. Being as rich as they were, of course, the Rockefellers did great damage as well as much good, and their kind of wealth is always, essentially, criminal—as Fran Lebowitz said, no one earns a billion dollars, you steal a billion dollars.

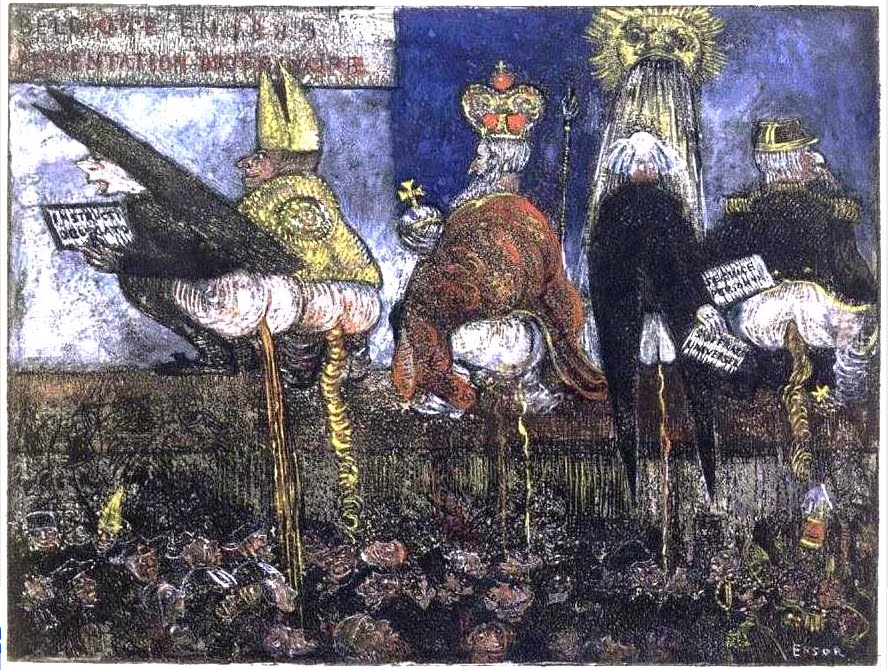

What we have now, however, waving its brainless sceptre at us from Washington, is unadulterated criminality, the antithesis of art, literature, philosophy, and any other higher things the human species has invented. (In a different moment, the notion of “higher things” might be met with deserved skepticism—but not now, not now.) King Turd, the trash swarming around him in the White House, his congressional enablers, and the hayseeds from the heartland who voted for him, haven't even the cultural pretentions of the Nazis, though they definitely have the mindset. A bunch of oafs, in truth: serenely corrupt, sadistic, amoral, foaming at the mouth on cue, and, frankly, as American as cherry pie.

Mike Hodges writes, “Sitting for the photo shoot with Merkel [Trump] looked like a gorilla in a zoo, bored and sick of being looked at.” People in New York have developed gestural and verbal shorthand to reference the ongoing political catastrophe in Our Nation’s Capitol and its prime, or primate, mover. (In Cuba, people used to stroke an imaginary beard to invoke El Supremo.) Often people stop themselves on the verge of uttering the despised name—“I’m not going to say it,” they'll say, or make a flinging gesture, one hand deployed like a tennis racquet, as if lobbing away all political dread into a manageable distance. Everyone struggles to regain a semblance of balance and normality without “normalizing” an intolerable reality by completely ignoring it.

I don’t envy anyone who has to produce commentary on this disaster on a routine basis. It’s almost impossible, and feels redundant, to articulate my own disgust and horror when hundreds, thousands of others have already articulated theirs. Everything to be said has been said—yet needs to be said again, often, and often by the same people, even every day, since every day of Trump brings another assault, usually several assaults, on sanity and democratic norms.

Yet the pushback can become numbing, and eventually loses its impact through the repetitive recitation of outrages. It’s part of the Trump-Bannon strategy to exhaust people’s capacity for outrage, to continually ratchet up the level of brazen absurdity and falsehood until everybody feels drained and powerless to fight back.

Fresh ideas are desperately needed, and in terribly short supply. It’s a great pity that so few journalists are capable of commentary at the level of Masha Gessen’s recent pieces in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and elsewhere. Few have her talent, her insight, or her long experience of living in, and reporting on, an authoritarian system. Moreover, many are obliged to produce commentary on a daily, or weekly, basis, even when they have little or nothing of value to add to the discourse—and therefore become part of what everyone needs to avoid, namely, the endless citation of horrors that can only produce depression and feelings of resignation.

There is a French word, abrutissement, that describes the cretinizing effect of a phenomenon like Donald Trump—someone so appalling and offensive to one’s sense of decency that he turns his adversaries into fulminating animals. This word may also connote the mesmeric effect of such a person—what Kluge calls “the charisma of the drunken elephant”—on credulous, stupid individuals.

Friday

“Cretinizing” is the first word that came to mind when I read about the controversy—a word I’ll avoid putting in quotes, though this particular controversy seems nugatory—surrounding Dana Schutz’s painting “Open Casket” in the Whitney Biennial. According to artnet news, “The central contention is that it is offensive that the painter, a white woman, would depict black suffering—and potentially profit from it.”

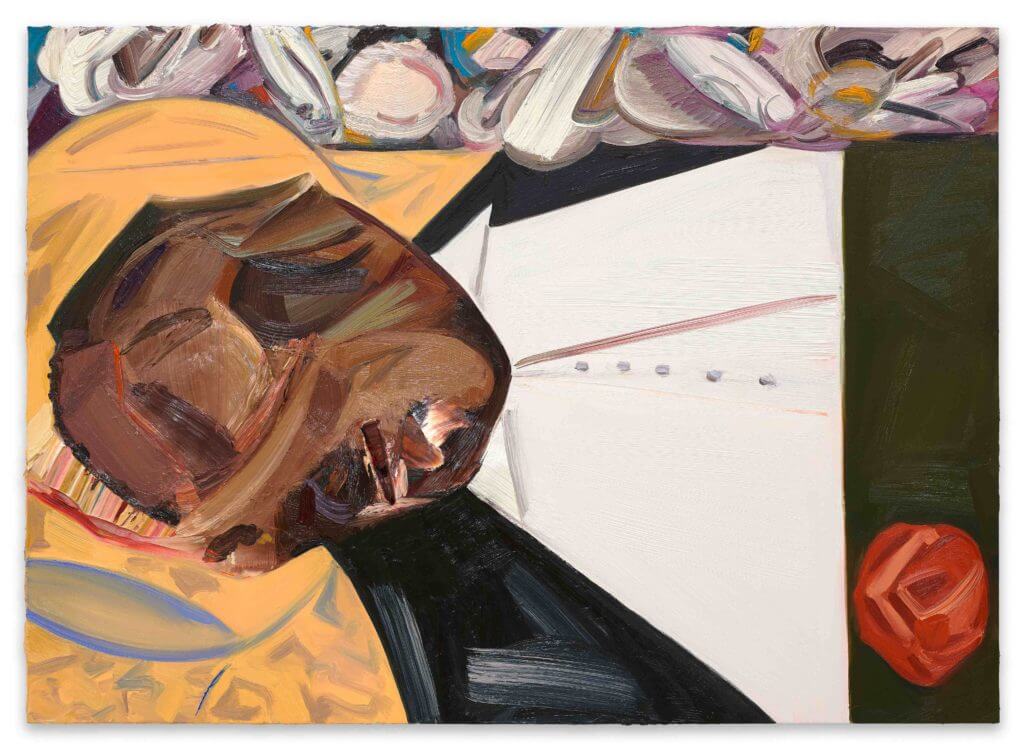

Schutz’s painting is a rather blowsy, abstract rendering of Emmett Till’s body in its open coffin; by her own account, she was moved to paint it “after a summer that felt like a state of emergency—there were constant mass shootings, racist rallies filled with hate speech, and an escalating number of innocent black men being shot by police.”

Evidently, the mere presence of this work in the Biennial, in fact the painting itself, “should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people,” according to a lengthy open letter sent to the Whitney by Hannah Black, ubiquitously described as a British artist based in Berlin, who also asked the museum to remove the painting “with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum.”

Black’s letter is a masterpiece of its kind—presumptuous, rhetorically coercive, self-aggrandising, opportunistic, and gratuitously insulting to Schutz and the Whitney curators, to whom she ascribes malefic ignorance and insensitivity about racial matters, if not something even more sinister. Even if they think they’re concerned with such, they’re not entitled to express this concern, except in a manner prescribed, one supposes, by Hannah Black. Emmett Till’s mother’s decision to reveal the damage done to his body by a white mob is only comprehensible to black people, since in Hannah Black’s estimation, only black people suffer grief and oppression; “Non-Black people must accept that they will never embody and cannot understand this gesture: the evidence of their collective lack of understanding is that Black people go on dying at the hands of white supremacists, that Black communities go on living in desperate poverty not far from the museum where this valuable painting hangs...” and so forth.

Black instructs us that “it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.” Thus Schutz's practice as an artist, simply because she is white, is reduced to a pursuit of “profit and fun,” though Black grudgingly allows that Schutz’s “intention may be to present white shame”—apparently, the only conceivable, if failed, intention of this artist—but “this shame is not correctly represented,” and “non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material.”

At the risk of causing further pain, Black or otherwise, it seemed obvious to me, reading Black's letter, that the author herself was ‘pretending to care’ about the emotional injury she claims Schutz’s innocuous painting inflicts on a black viewer. In reality, Schutz’s painting serves Black as an almost arbitrary pretext for a cliché-riddled, race-baiting demagoguery, calculated to ensure many seasons of earnestly pointless panel discussions, starring none other than Hannah Black.

“Even if Schutz has not been gifted with any real sensitivity to history, if Black people are telling her that the painting has caused unnecessary hurt, she and you must accept the truth of this.” Well, no. The only black, or Black, people who have mobilized around this outrage are Hannah Black and cohorts of hers who happen not to have been included in this edition of the Whitney Biennial, and one would be wise not to “accept the truth” offered by anyone channeling Savonarola without a good deal of skepticism.

Of course, the Whitney sets itself up for this kind of thing by assembling a survey of current American art while trying to redress the relatively sparse inclusion, in previous Biennials, of women artists and artists of color; inevitably, however curators go about putting these things together, an element of arbitrariness finds its way in, along with the influence of social connections, chance encounters, et cetera. Every Whitney Biennial comes in for harsh criticism, although, perhaps in keeping with the current extremist zeitgeist, this is the first one where someone actually proposed destroying a work in the show.

The art world, like most cultural microcosms, is riddled with contradictions and arcane codes; some of it resembles any other luxury business, some of it is pinch-penny fringe, and for some years the upper end of the market has had precious little to do with the actual value of anything, much less the meaning of anything; most of the art market is about laundering money, evading taxation, and parking capital, and the cash value attached to today’s canonical art is simply a figure agreed upon by a closed circuit of billionaires, who pass insanely overpriced garbage, along with masterpieces (at that level, what’s the difference?), back and forth like kids trading baseball cards.

Saturday

I had thought to write something about the depiction of the art world in films and on TV, which has always been pretty wank, even egregious, although one could argue that films and TV never much resemble reality, from which most people want to escape as often as possible anyway, for as long as possible. The most trite and ubiquitous visualization is “the gallery opening”—in all fictional representations, a momentous event, at which vast fortunes are flung at up-and-coming artists, myriad financial and sexual intrigues unfold, and all manner of giddy, pseudo-intellectual claptrap is bantered by vapid socialites.

In reality, most art openings are about as exciting as an inflamed hemorrhoid, and there isn’t much in the real thing for the camera to exploit: typically, a big white cube or rectangular space with stuff on the wall, sometimes other stuff planted on the floor, and a bunch of people standing around, drinking mediocre white wine from plastic cups. The movies jizz this up by turning it into a designer costume drama and supplying everyone with champagne flutes, but in either case the art on display is either real and looks bad or fake and looks worse.

I think the first contemporary film I saw that featured an art opening must have been An Unmarried Woman, with Alan Bates playing a lusty, Promethean Modern Artist of the macho Cedar Tavern variety. Years later, a friend who worked at the DIA Foundation when the film was being prepared told me that Paul Mazursky's art director had called her to ask what sorts of edible things might be offered at an opening; she recommended celery sticks, sliced carrots, and tiny tomatoes, with a little bowl of dip in the middle, and was highly gratified to see exactly these things featured in the movie.