Feeling Nowhere

Sam Stephenson

September 10, 2019

“I once fucked Jesse Helms and it was the worst sex I’ve ever had.”

Perry Farrell muttered that line into the microphone on stage midway through a show at the University of North Carolina’s Memorial Hall on Tuesday, November 13, 1990. The frontman of Jane’s Addiction, drenched in sweat, his junk hanging out of women’s lingerie, shared bong hits with fans in the mosh pit and doused the front rows with red wine. Later he pulled a small bowl pipe from his boot and shared that too. Farrell was about five-foot-nine, 135 pounds, with shoulder-length black dreads, his body sinewed by drugs and surfing.

Farrell had begun the show wearing a long black women’s raincoat. He talked often to the audience, which was more diverse than most loud alternative rock shows, with some black and Latino fans, and many women by themselves or in small groups. Amid the sold-out hall were punks, metalheads, hippies, and college kids. There was also a significant LGBT presence.

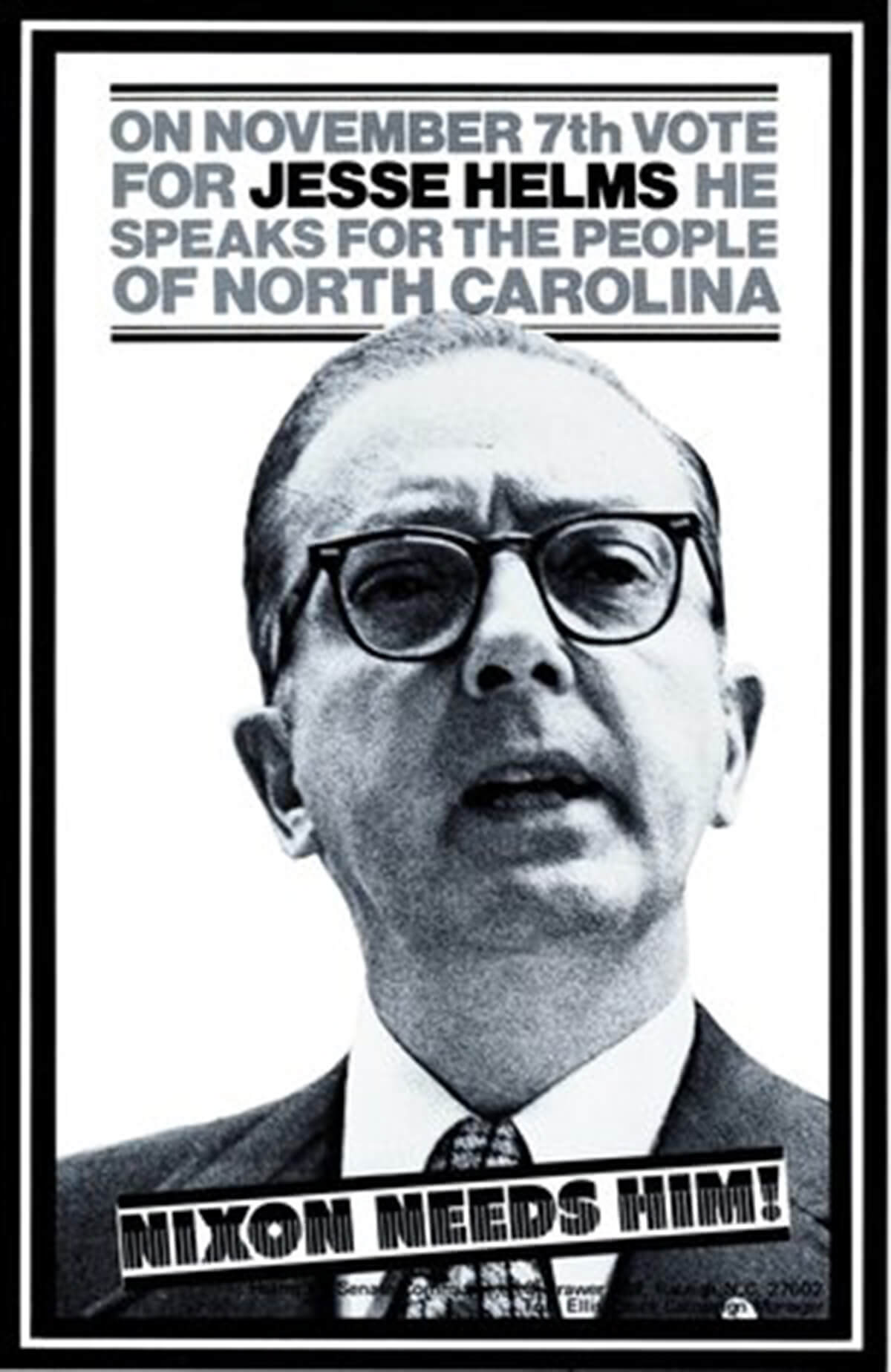

Mid-term elections had occurred the previous Tuesday, with the nation watching North Carolina’s senate race. Controversial conservative incumbent Jesse Helms beat Harvey Gantt, an African-American mayor of Charlotte, after the latter led polls for most of the race. There were widespread complaints of voter suppression, in the form of intimidating postcards mailed by the GOP to predominantly African-American precincts with false warnings about illegal voting.

Americans were living through essentially the third term of Reagan-Bush. With George H.W. Bush as his vice president, Ronald Reagan slashed taxes in the upper brackets and quadrupled defense spending. Then Bush became president with the help of a notorious ad about Willie Horton, an African-American convict who committed several felonies including rape while on furlough. By the time of the Jane’s Addiction show the Bush administration was ramping up war with Iraq over Kuwait, a country smaller than South Carolina.

I hadn’t thought of Jane’s Addiction for nearly three decades until last year’s mid-term elections, which made me remember the 1990 mid-terms. The stakes seemed epochal, then and now. I told a friend, a former college radio deejay who is now a judge, that I was interested in researching the band against the backdrop of the late 1980s and early 1990s, how that story may resonate today.

He pointed me toward a long article published on July 18, 2018 in Splinter entitled “How Jesse Helms Invented the Republican Party.” Written by Nick Martin, the article details how today’s hard right GOP didn’t begin with Reagan in 1980, but with Helms in 1972 when he was first elected to the Senate, the same year Nixon’s reelection bid carried 49 states. Helms had become a public figure in North Carolina in the 1950s with rightwing five-minute monologues on WRAL radio and television in Raleigh that provided a playbook, wrote Martin, for how Fox News would come to operate 24 hours a day.

The first time I heard Jane’s Addiction remains clear in my head. It was 1987 and the track was their cover of “Rock & Roll” by the Velvet Underground. I heard it on WXYC, the legendary student station located on campus in UNC’s Student Union, and then soon afterward on a friend’s mixtape. Farrell’s voice sounded unusually enigmatic, desperate guttural grinding mixed with childlike cooing, often in the same line. Who in the hell is that? A man? A woman? A man and a woman? A teenager?

I began digging into archives on Jane’s Addiction and conducting my own oral history interviews. I found material that validated my three-decade-old feelings from that show in Chapel Hill and the band in general. Boston Globe columnist Renee Graham wrote that amid their decibel-pushing metal qualities, Jane’s Addiction maintained “a gorgeous feminine sensibility.” Yoko Ono, introduced to the band by her son, Sean Lennon, said that the first time she heard them, “My bones immediately relaxed.”

I’m not an iconographer, so I wasn’t interested in establishing Jane’s Addiction’s importance in music history. Tom Morello, the Kenyan-American guitarist for bands such as Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave, and Prophets of Rage, already did that with more authority than I could anyway. In a letter published by Billboard in November 2016, Morello argued for Jane’s Addiction’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (a futile effort still today), writing, “Jane’s Addiction are the Sex Pistols of the Alternative Nation, a small, brilliant catalog of songs and a shocking, groundbreaking ethos that changed music forever.“ He described their music as “savage but beautiful,” adding, “they didn’t look or sound like any band in the history of rock and roll.”

A review of the Chapel Hill show was published in UNC’s student paper, The Daily Tar Heel, on November 15, 1990. Senior Jonathan Poole called it “one of the more eagerly anticipated shows ever to hit Memorial Hall.” He described the music as “a tormented and demented form of psychotic rock” and Farrell “a bizarre, deranged stage presence” akin to Tim Curry’s cross-dressed character in The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Poole boldly predicted that Jane’s Addiction’s “style and power” would “dictate the genre of rock in the future.” He couldn’t have known that members of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and the Smashing Pumpkins, among others, were taking note of the surprisingly popular frenzy Jane’s was kicking up across America and Europe, but he knew something new would emerge in their wake.

Two weeks after Chapel Hill, a music journalist in Montreal, Mark LePage, reviewed the band’s show in that city for The Gazette. He declared them to be “LA’s gutter art rock terrorists,” and then went on to write that no other band had created a “communal feeling” like Jane’s Addiction had in Montreal that year.

.jpg)

Jane’s Addiction’s ethos of danger and community, at once challenging and welcoming, was easier to feel in the moment than to access today via recorded sound or image. At the height of the AIDS scare, rumors prevailed that Perry Farrell had been a gay prostitute. Tom Morello, an admitted former stripper himself, described Farrell in his Billboard letter as “a former homeless sex worker drug addict” and given their shared backgrounds in LA it seems logical that Morello would know.

The stringy Farrell, who was 30 in 1990, was a wildly unpredictable character on stage, like Charlie Chaplin’s tramp as a cross-dresser on heroin, cocaine, and LSD. Eric Avery, the band’s 25-year-old bassist, was six-foot-one and 150 pounds with long pink hair, his subtle rhythmic movements honed from many teenage nights in R&B dance clubs around LA. The Mexican-American guitarist Dave Navarro, age 22, was a skinny five-foot-eight and 130 pounds with long black stringy hair over his face, dark sunglasses always over his eyes. Avery, Navarro and the long-haired drummer, Stephen Perkins, also age 22, rarely wore shirts, but the effect was more boyishly androgynous than masculine. The musicians never made eye contact with each other. They were in their own worlds, communicating only with the music, and never smiling, adding a sinister feel to the performance. No one knew how to categorize their presentation. One L.A. fanzine writer commented, “I wouldn’t be surprised if these guys are all fucking each other.”

The poet Matthew Zapruder first saw Jane’s Addiction in 1989 when he was music director of the student station at Amherst, and then many times over the next two years. “They looked kind of like very handsome alien bugs,” he told me. “They were magnificent.”

*

Perry Farrell was born Peretz Bernstein in Queens, NY. His mother committed suicide when he was three years old. His father, a jeweler, moved the family to Miami where Perry learned to surf. He moved to Los Angeles after high school. He took the name Farrell, which was his brother’s first name. An ambitious and idiosyncratic charmer, Farrell had a different constitution. In his prime Jane’s years he was known to do heroin and cocaine in cycles for 24 hours and then jog 10 miles on the beach and go surfing. In the early days, he handcrafted fliers for the band’s shows and posted them all over L.A. He penned the band’s lyrics and projected his haunting vocals through an echoing delay device.

Eric Avery was born in downtown L.A. and raised in various Westside neighborhoods and beach towns, living with his family in as many as ten different addresses, according to his half-sister, Rebecca. His parents divorced when he was five and his mother soon remarried to a Hollywood B actor and had Rebecca. Avery buried the trauma of his parents’ split until it came rushing to the surface when an aunt innocently asked, “Do you ever think about your biological dad?” He started drinking in the eighth grade and was kicked out of a number of schools.

By 14 Avery was playing bass by himself and surfing all day, dancing in clubs at night. A deep thinker, his singularly undulating and hypnotic bass style was developed on his own, without a band or songs in mind. His first stint in addiction rehab was when he was 16 years old. There he met the musician Carla Bozulich who later introduced him to Farrell. Sharing an appreciation for Joy Division, the Velvet Underground, David Bowie, and Flipper, among others, Farrell and Avery founded Jane’s Addiction, the name inspired by their housemate, Jane Bainter.

Farrell and Avery tried a number of drummers and guitarists in the summer and fall of 1985. None were working out until Rebecca suggested her 18-year-old boyfriend, Stephen Perkins, and his best friend, Dave Navarro, both of whom were steeped musically in hard metal (Black Sabbath and Slayer) and the Grateful Dead, a rare combination. Young and fearless and extremely talented, Perkins added primal backline power and Navarro distortion and dripping, drilling riffs to Farrell’s madcap vision and voice and Avery’s relentless rhythms.

Navarro’s parents were divorced and he was abused by his mother’s boyfriend, once handcuffed by him to a toilet. This man later murdered Navarro’s mother and aunt but he wasn’t caught until eight years passed, partly because plastic surgery had made him unrecognizable. He was found by the TV program America’s Most Wanted. In 2015 when Navarro made the film Mourning Son about the experience, Perkins, his friend of nearly four decades, said he had never known the severity of young Dave’s trauma.

The fifth member of Jane’s Addiction was Farrell’s longtime girlfriend, Casey Niccoli. She moved to Los Angeles after high school in Bakersfield and soon began dating a musician in the band Lions and Ghosts. After she met Farrell they moved in together. She held down two day jobs, first as a licensed esthetician and then an office administrator, during the early days of Jane’s, enabling Farrell to devote himself full-time to the band (Avery worked in a shoe store in Santa Monica). During the band’s heyday, she and Farrell were the first couple of the L.A. underground. He once described her as “a punk Elizabeth Taylor.”

Niccoli is depicted on the cover of both of the band’s iconic albums, Nothing’s Shocking (1988) and Ritual de la Habitual (1990). She also co-directed (with Farrell) two films featuring the band, “Soul Kiss” and “Gift,” and an MTV-award winning video for the band’s song, “Been Caught Stealing.” In a number of interviews from around 1990 Farrell gave her credit for many of the band’s ideas and style.

*

.jpg)

Early in the evening of November 13, 1990, I drove my two-door Toyota Corolla the 20 miles to Chapel Hill from my apartment in Raleigh. On the way I picked up my friend, Eugene Eaves, in Durham, where we left his two-door Honda Civic in the parking lot of a strip mall behind a 7-11.

It was a typical crisp fall night in North Carolina’s Piedmont region. The temperature reached 57 degrees that sunny afternoon, overnight down to 37. The leaves on hardwoods were drying and beginning to turn yellow, orange, red, and brown. Gene and I parked near the theater and walked downtown to have a few beers before the show.

Memorial Hall was built in 1930, a brick shell with no air conditioning and 1400 small uncomfortable folding wooden seats. I had sweated through my older brother’s law school commencement in that room as a teenager in 1982. Across the street, the state’s flagship National Public Radio member station, WUNC, was housed in the 700-square-foot, mildewed basement of Swain Hall, built in 1914. On one side of Swain was the Scuttlebutt, a small university-run convenience store that sold self-serve fountain drinks (“No Free Sips!”), bubble sheets for multiple-choice tests and Blue Books for essay exams, and Playboy, Playgirl, and Penthouse magazines.

Gene and I had met in Charlotte that January in a corporate banking training program at First Union (now part of Wells Fargo), our first jobs out of college. I had majored in economics at UNC and Gene had majored in finance at North Carolina A&T, a historical black university an hour away in Greensboro. On the 19th floor of First Union Tower, my prefab cube opened into his and we shared the same floor-to-ceiling window looking over the city.

We hated our jobs and spent most of each day talking about music. On Saturdays we went to The Record Exchange and Repo Records to trade in records and browse. One weeknight we went to hear Black Uhuru play a set that started at midnight. The next day on the 19th floor, we took turns napping under our desks, in our suits, keeping look out for one another. It became evident we weren’t long for those jobs. Gene moved on to a credit union (a decade later he gave me a loan for a used 4-door Honda Accord wagon). I moved to Washington, D.C. to work in economic policy, first at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and then for a democratic member of House Ways and Means from Wisconsin.

When I began researching Jane’s Addiction last year, Gene was the first person I called. He reminded me that we didn’t have tickets for the show that night; that we had planned to scalp. But scalpers were getting up to $50 for a $17 ticket. So we snuck in the side door of Memorial Hall. We arrived just in time for the opening act, 24-7 Spyz, a black funk-reggae-metal band from the Bronx.

I asked Gene what he remembered feeling about Jane’s at the time. He told me, “They were fucking weird, and I felt a little weird for liking them. Their music coursed with an edgy pan-sexual energy with a hazy druggy veneer. Definitely drug music. The sound of pinned-out eyeballs. I’ve heard the Stones described as Chuck Berry with a joint, switchblade, and an erection. Jane’s was an ersatz bizarro-world Zeppelin with a syringe, a shiv, and a strap-on. They felt compelling in a whole new way. Even though I just went there, I often think the Zeppelin comparisons are a little lazy—low hanging fruit. If anything, Jane’s more embodied the fearless adventurousness of the Westbound [label, early 1970s] era of Funkadelic, which also provided that same shock-danger titillation, and like Jane’s, listening to Funkadelic was a seedy experience. You either got it or you didn’t. You weren’t on the fence about these guys. If you got it, you were part of a small community.”

*

One reason I didn’t listen to Jane’s for thirty years was because I was professionally involved in research of an underground jazz scene in New York City in the late 1950s and 1960s. For two decades I listened primarily to jazz, the more obscure the better. In that scene, smoking weed was like drinking coffee or Rheingold beer, a daily routine. Harder drugs were a private matter, not a party element. Over the years many jazz musicians grew weary of associations with drugs—a cliché, they said, or a trope, especially when it came at the expense of focus on the rigor and craft required for jazz to be good.

But to deny drugs a role seems simplistic. The musician and writer Mark Stryker uses the term, “muscular vulnerability,” to describe the effect drug addictions had on some jazz musicians in the 1950s and 60s. The “enforced relaxation” of heroin combined with the urgency to prove oneself were at least in part elements, Stryker says, influencing the seductive sounds of musicians like pianist Sonny Clark and saxophonist Tina Brooks, both of whom died young from overdoses.

This line of thinking applies to Jane’s, too, including the part about rigor and craft. People close to Jane’s have told me the band practiced eight hours a day for their first two years, treating it like a workaday job, and that Farrell was “a task master.” In a productive burst from January 1986 to April 1987, they recorded demos of 18 songs that would make up their primary repertoire for the next five years.

Jane’s cauldron of intelligence, tenacity, audacity and vulnerability produced an unpredictable and messianic vibe, often coming with unthinkable humor. In a 1987 interview on the radio station at Loyola Marymount, KXLU, the tape of which was shared with me earlier this year by the L.A. musician Bill See, Farrell told a story about living in a group house on North Wilton Place near Hollywood, a house that is now a fulcrum of the band’s lore. Each tenant had an assigned area of the refrigerator to store their food. Farrell’s food became increasingly missing and he was fed up. So he took a package of his cheese, masturbated into the container, closed it and put it back. The next day his cheese was gone. A week later at the regular house meeting he told his housemates what he did. Then he scanned the room looking for a facial expression identifying the perpetrator. In the interview, he didn’t reveal the results.

*

I emailed Jonathan Poole after finding his review of the Chapel Hill show. He lives in Raleigh today with his wife and two sons and works as a sales manager with a software company. A serious guitar hobbyist since high school, he remarked, “That Jane’s review was one of only a handful I wrote for the paper. It felt important to me, the music and what Jane’s represented. There’s plenty of ‘80s and ‘90s nostalgia out there today, but the feeling people had when they listened to Jane’s at the time has been lost. I recently went back to Nothing’s Shocking and realized it was released in August of 1988. That is so early. There was nothing in the alternative world that heavy at the time, nothing close to it.”

I wrote to Jill Balloun Webb, who had been the student president of the Carolina Union Activities Board responsible for originally booking Jane’s Addiction in Memorial Hall. She now lives in Wilmington, N.C. with her family and makes murals and other public art. She said:

It was important to me to book Jane’s Addiction if we could. Our advisors (full-time university staffers) were skeptical because of the rumors of widespread drugs that followed the band. It was a cultural disruption. We were able to argue that it would be an instant sell-out (it was) and that it would be an important contrasting atmosphere for the students. There was such a contrast between old and traditional Memorial Hall and what Jane’s Addiction would bring into the space. I got behind it more than any other show during my tenure as president. It was unusual for us to be able to book a band as edgy and as unpredictable as Jane’s Addiction when they were at the top of their game. The day of the show was surreal. I had this numb feeling. I mean, pinch me, is this really happening? It felt unpredictable and slightly dangerous. I went to the show with a group of girls, my roommates and best friends. I’m not a habitual risk taker in my personal life, but I believe that good change comes from taking risks. It makes people uncomfortable but good change can come after a while of feeling uncomfortable.

Jesse Helms despised everything about Chapel Hill and UNC, railing against the university often in his radio and television commentaries, protesting that the school promoted communism and interracial “mingling.” When a state zoo was proposed, he remarked, “Why build a zoo when you can just put a fence around Chapel Hill?” He would have wanted no part of the group of people that were moved by Jane’s Addiction.

Through a friend, the writer Kristine McKenna, I found my way to Anna Skarbek, a visual artist working with filmmaker David Lynch. She told me:

When I was fourteen or fifteen years old I was growing up near College Park, Maryland. My mother was a computer scientist at NASA. I listened to WHFS [a pioneering alternative commercial radio station now defunct] all the time. The Cure, the Smiths, the Pixies, Fugazi, all those bands. Then Ritual de lo Habitual came out. The only thing that struck me as hard as Jane’s Addiction was David’s show, Twin Peaks (and years later Mulholland Drive). What Jane’s shared with Twin Peaks was a certain mood, a haunted mood. There were aspects of Jane’s that related to voyeurism, and the taboo; their look was androgynous, strange, dark, and sexy. I was so struck by that mood, the colors and textures and stage decorations the band used. Perry alone was such a striking character and there were those rumors that he had been a street hustler and maybe had AIDS. They built a foreign, scary and exciting world that you could enter if you were drawn to it. Sometimes it took one small thing to access to that world, like the photograph of the band on the back of Nothing’s Shocking, one song or one part of a song, and you were exiting your world and entering one you didn’t know. They had an extra layer to their art that nobody else had, not Nirvana or anybody that I’d heard. Their music and imagery were transporting.

Another friend, the saxophonist Levon Henry, introduced me to Sean Schuster-Craig, a musician who performs as Jib Kidder and now lives in Ann Arbor, MI with his wife and two children. He said:

Jane’s had something of the union of opposites, the amateurish with the virtuosic. I think art needs both the yin and the yang. I think of outsider artists as “already comfortable” or “born comfortable” or to borrow Bolaño’s phrase, which I love, “born orphans,” in terms of expression. Not needing to learn their father’s birdcall. Born Orphans would have been as fucking apt a band name for Jane’s as Jane’s. The head start in not learning your father’s birdcall is not having to unlearn it.

I’m closeted transgender, and I first wore women’s clothes when hormones kicked in, when I was 12, and I imagine now this is a huge part of why Jane’s came to the forefront for me. Nirvana and the Meat Puppets also wore women’s clothing but it was more of a joke, it seemed.

Ages 10 to 18, I just tried to get my friends into some small subset of the music I was into, just to try and have some overlap with somebody, because, at least as far as listening went I was always a step ahead back then, and I had my first major success in middle school when I got my best friend Doug into Jane’s. He was gay in the closet. We were both children of addicts, he would shoot up the heroin his older brother, a dealer, would ship him (in some perverse brotherly attempt to mollify known familial pain), I would smoke the soft pack Camel Lights he’d steal from his dad’s car or Eckerd’s Pharmacy for me, to join him in his deadly ritual as far as I was willing to. Doug would do these amateur pencil sketches of Perry and generally try to dress like him, I’d think about the meter of “Then She Did.”

I relate to masculinity as little as I do to codified notions of transgenderism. I will always feel nowhere in so many ways and that is exactly where Jane's resided, in the red room, on the edge of a knife, they really were. I was exposed to so much music young, but they really were my first contact with the unclassifiable. I followed them like pan right into the fertile zone of the unclassifiable, like imagining genre as creative Roundup, enforcing false borders and killing half the bugs in the world.

*

Jane’s Addiction broke up in late 1991 after headlining the first Lollapalooza festival, which was created by Farrell. The band had been splintering for years, on speaking terms off and on, in and out of various substance rehabilitations, but held it together long enough to put forth a number of electrifying performances closing the festival.

1991 was also the year of the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas hearings and the videotaped Rodney King beating by L.A. police.

On February 26, 1992, the manager of the 1990 Senate campaign of Jesse Helms, Carter Wrenn, signed a decree to settle a Department of Justice lawsuit claiming the Helms campaign had authorized the mailing of 125,000 intimidating postcards to black precincts, falsely telling voters they were not eligible to vote (Helms won the race by 105,507 votes). Wrenn told the Associated Press, “The so-called civil rights bureaucrats left us no choice but to sign this agreement,” saying the campaign did not review the mailing nor have any idea who received it or how many were mailed. “The Helms for Senate Committee made this settlement for one reason: it did not have $250,000 to take the Washington bureaucrats to court.”

In November of that year the presidential ticket of Ross Perot and Admiral James Stockdale would win an astonishing 20% of the vote running as independents with pride in ignorance of Beltway politics, a sign of things to come in our culture.

Perry Farrell was 32 years old when Jane’s originally broke up. Casey Niccoli was 27. Eric Avery was 26. Dave Navarro and Stephen Perkins were both 24. Their groundbreaking work was done.