A Japanese Philosopher in Pre-War Paris

Kyle Chayka

December 18, 2017

I. FORTUNE IN, DEMONS IN

Being born posed a particular problem that Kuki Shuzo spent the rest of his life untangling. The fateful event occurred in Tokyo on February 15, 1888, under the care of his father, Ryuichi, a Ministry of Education bureaucrat turned baron-diplomat, and mother, Hatsu, a former geisha. Kuki suffered no more trauma than such an occasion usually entails—the problem was that it happened in the first place. Why should he have been born when, where, and who he was? Why to his parents and why in Japan, as opposed to France, Egypt, or perhaps America? He is plagued by uncertainty and yet drawn relentlessly to its abyss, like a skier down a mountain slope.

The characters of the family name Kuki can be read to mean Nine Devils. It also suggests the name of a fish, or a mountain grotto. It might refer to an oceanside village where pirates once landed, Kuki discovers. Nevertheless, at each New Year’s ritual since ancient times, the family has called out a unique invocation, “fortune in, demons in,” as opposed to the usual welcoming of the former and exorcising of the latter. Later in life, as a philosopher, refusing simple dichotomies becomes Kuki’s habit. He favors an approach from all sides at once. He carefully marks his position and then disappears from it, only to appear at its opposite point. Let the fortune and the demons come, he feels: accepting both is not a choice but a fundamental part of his nature.

Another rift in the child’s psyche: Before Kuki Shuzo’s birth, Ryuichi had been stationed with Hatsu in Washington, D.C. Along came Okakura Kakuzo, a lesser Ministry of Education bureaucrat and scholar who would go on to write The Book of Tea in English, an influential bridge between cultures. It is decided that Okakura and Kuki’s mother should return to Tokyo together before Ryuichi, and on the month-long journey they begin an affair that eventually splits the Kuki family. Kuki Shuzo grows up a child of divorce, moving between homes, seeing Okakura at his mother’s and cultivating the seed of doubt. Could his parentage be…? Kuki later calls Okakura the aesthete and wanderer his “spiritual father.”

In Kuki’s youth, Tokyo is rising; neoclassical stone train stations loom above the city’s traditional wooden storefronts and peak-roofed houses. There are more foreigners than ever before in Japan, and the country’s intellectuals are working to understand the distance between self and other, how to incorporate the influences of western modernity without losing a native Japaneseness. Kuki is the scion of a prominent family and a student at the prestigious First Higher School studying German law in the hopes of becoming a diplomat. He is subsumed by the debate: Will his future belong more to the West, or to his homeland?

Introverted and self-serious, maybe Kuki wasn’t as good a student as he expected to be. In 1905 he fails a history class and falls into literature and philosophy instead. (His schoolmate, Tanizaki Junichiro, is to become one of the most famous novelists of his century, annotating the shifting social norms of Japan’s exposure to the West.) At 21, Kuki enters the Tokyo Imperial University and studies philosophy under the Russian-German Raphael von Keober. In 1911, 23 years old, he decides to convert to Catholicism. Freedom of religion had only been codified in 1871 and the religious community is still new—there are only some 80,000 Catholics in the country.

The conversion is a marker of difference, a way for Kuki to reach beyond his birthplace. Is it truly newfound faith, or is it more like an inoculation, a way for Kuki to incorporate his philosophical influences (the languages he learns, the books he reads, the essays he writes) at the deepest possible level? He commits to his ethos of everything-at-once. Kuki chooses the baptismal name of Franciscus Assisiensis, after the medieval founder of the Franciscan order. Francis is an austere and itinerant saint, a cosmopolitan ascetic—strange choice for a rich city kid. Kuki dissolves these endless contradictions like the communion wafer on his tongue.

In 1917 Kuki’s older brother Ichizo dies. Kuki marries his widow, Nuiko Nakahashi. It is a family responsibility, but he doesn’t mind. Nuiko is withdrawn and mournful, and anyway, Kuki is a longtime patron of old Tokyo’s lantern-lit pleasure districts, where the illumined dusk heightens all fevered ambiguities. Literature poses theories; the city at night proffers the life of the body. The new, modern restaurants and movie theaters incant international dreams. The usherettes are required by law to wear underwear beneath their kimonos, sleeves brushing aisle seats in the supercharged dark. Kuki is 30 years old. His work has barely begun, but his vaporous sensibility—all of this might never have existed in the first place—he already feels within himself like an intoxicant, like the whiskey warming his stomach at a bar. The years go by in pages.

II. THE POSSIBILITY OF BECOMING

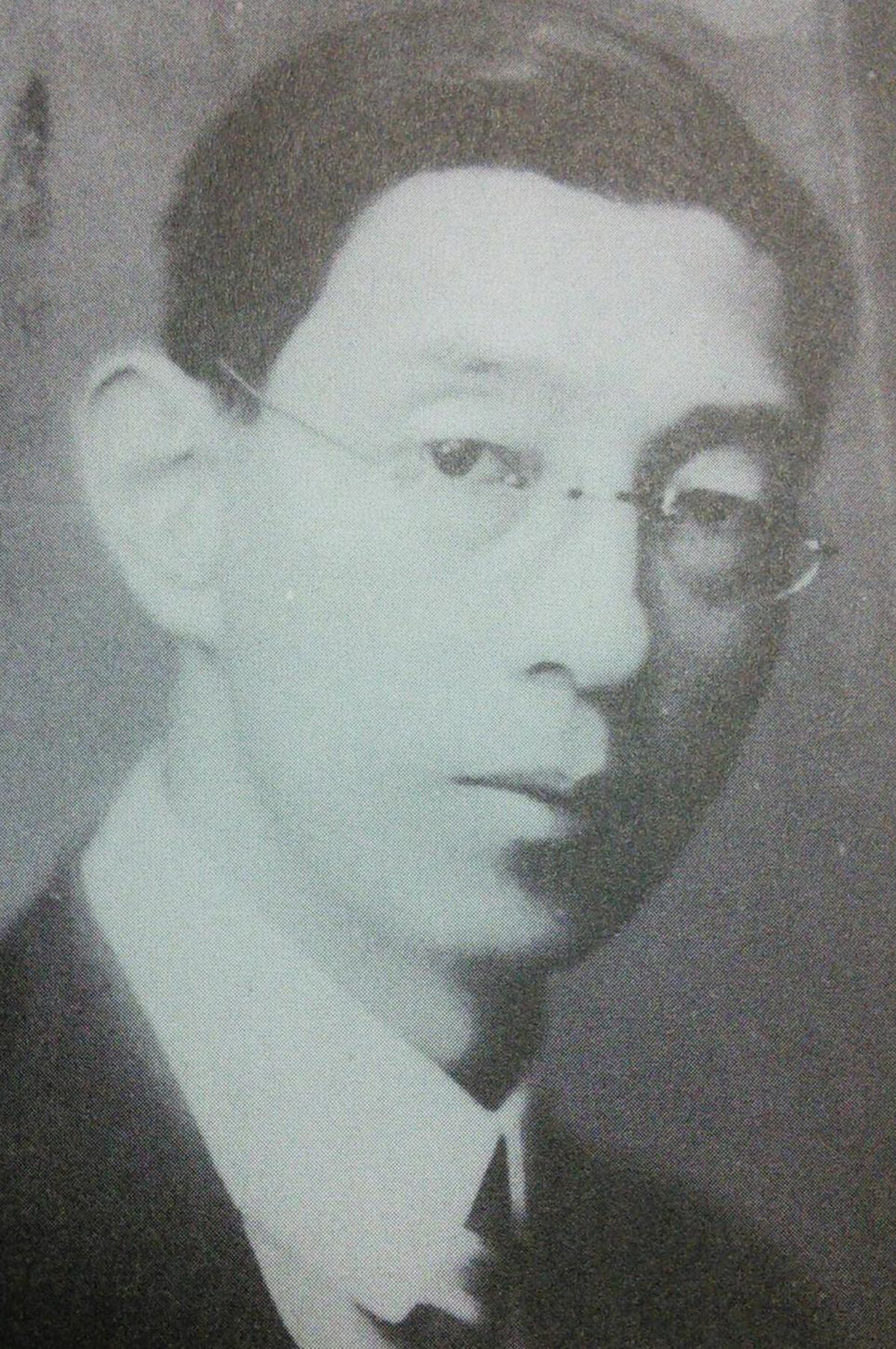

Kuki travels to Europe in October of 1921 at the age of 33, under the guise of the Ministry of Education. Nuiko joins him, but the trip is his own. On the boat from Tokyo there is a feeling of relief, the anticipation of finally experiencing what he has been studying, to live in the explosion of continental philosophy rather than dissect its frameworks in the study. Does life begin when he eventually lands in Marseilles in 1922? He is struck by the sudden possibility of other lives, all the people he could have been besides the patrician academic that he is, ambivalently married; tall and wire-thin, with an elongated face, beakish nose under round glasses, and perennially pursed lips; dressed in crisp western suits that, though expensive, feel superficial, like a costume.

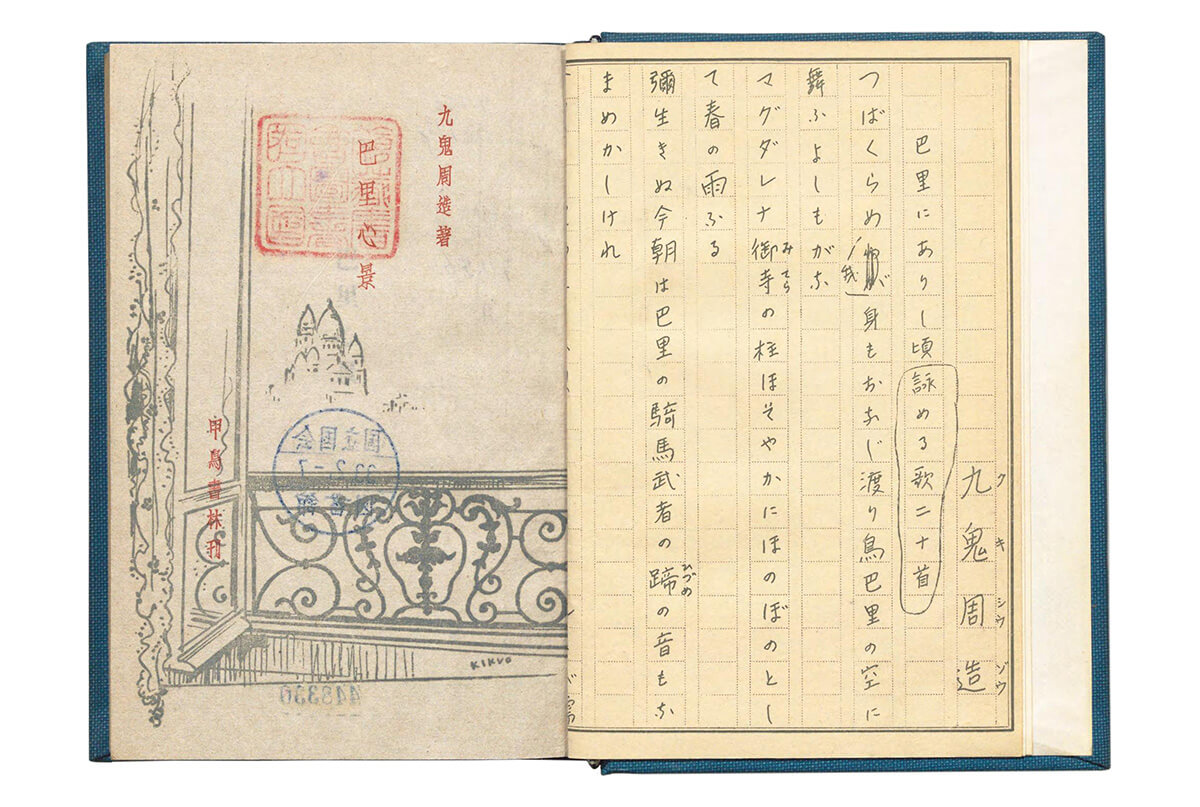

He studies in Heidelberg, but it’s in Paris in 1924 that everything becomes clear, or rather beautifully muddled. It’s not just the Americans—Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Stein—who are losing themselves in the city at the time. Paris seems to exist on a deeper level of sensation. Lighting out from the rooms he shares with Nuiko, Kuki wanders, sees the blue sky over the Arc de Triomphe, tulips in the Bois de Boulogne, pigeons in the Park Monceau, and yellowing chestnut trees lining the serpentine streets. He documents the passing moments in short, melancholic poems that he submits to journals back in Japan under the alias S.K., separating them from his academic reputation and stature as a Ministry of Education attaché. They are the opposite of his philosophy, personal and intimate, even maudlin. Kuki embarrasses himself with his sincerity, a teenager scribbling in his diary addressing his absent crushes:

I make a smile

Since you scold me

Saying,

“You look sad

Even when dancing.”

It’s a kind of adolescence. Nuiko stays in while Kuki establishes himself firmly in the city’s demimonde, attending opera, theater, dances, and dinners in equal measure. He begins to feel more at home in his suit. At the galleries and salons Kuki is exotic, but the scene is equally exotic to him—a mutual curiosity flowers. He is falling in love over and over again, with Yvonne, Denise, Louise, Henriette, Rina, and Yvette, whom he praises in poems and ranks in a list of dates. They form the city’s geisha class: consorts and concubines, dance-dates, women of pleasure.

Opened by an American madame with international mafiosi as investors, Le Sphinx is the first high-end brothel on the Left Bank, in the otherwise staid neighborhood of Montparnasse. Egyptian themed, with murals by the Dutch Fauvist painter Kees van Dongen, it is as much a bohemian club, with a “quiet atmosphere of a delicate, amiable and exquisite participation, reigned in a diffused pink light,” as a local nightlife chronicler later describes. Simone de Beauvoir considers Le Sphinx tacky but sincere. Henry Miller and André Salmon frequent it. So does Kuki the foreign philosophe. He makes no excuses for his escapades. In a poem, he brags that the blood of Don Juan runs in his veins.

When not otherwise occupied, Kuki focuses his scholarly efforts on the emerging discipline of phenomenology, following the German philosopher Edmund Husserl and his disciples, like Martin Heidegger. Phenomenology is consciousness, the feeling of feelings, the transformation of the external world into thought and back. The problem of his particular birth Kuki came to see as an iteration of the concept of contingency, “the possibility of becoming on the part of what is not,” as he writes. There is nothing, and then there is something. Why, or how? Seen one way, contingency is fate; another, it’s nihilism. To augment his studies, Kuki takes weekly French lessons from an activist and student named Jean-Paul Sartre.

Unlike the painters in their garrets, Kuki has no need of patrons or partners. Money is never a problem. There is always more of it for whatever is necessary, and so much is necessary: Endless bottles of wine, cartons of cigarettes, restaurant bills, theater tickets, new suits, and constant gifts and favors for women. When he becomes tired of the theater and the dances Kuki returns to his discipline. Reading is a way to treat the loneliness and homesickness that plagues him. He is back home in books, nostalgic for his student years. He remembers his Christian namesake, Francis of Assisi, and undertakes temporary spiritual diets away from temptation. He feels like Kant and Baudelaire fighting in one body. The two sides seem impossible to reconcile—and so he shuts the books and returns to the brothels.

In 1927, when he is 39 years old, Kuki decamps to Germany. There he studies phenomenology with Husserl at the University of Freiburg. At Husserl’s home, he also meets Heidegger, making a lasting impression on the philosopher, who had just published Being and Time and was yet to be known for his contribution to Nazism. On returning to Paris in the later half of 1928, Kuki is invited to give the prestigious Pontigny Lectures. Now he is a known figure in the intelligentsia, this foreign samurai, as others call him. This baron or count, as he sometimes identifies himself. His lecture subjects are the cyclical nature of time in Oriental thought and the expression of the infinite in Japanese art, his own culture explained in the phenomenological language of the other, to an audience of the same. And then in January 1929 he leaves for good, back to Japan. He never returns to Europe.

But Paris remains in memory forever after: Steamed flatfish and sea urchin with lemon at Prunier, one of the city’s glamorous restaurants. Pacing the cobblestoned banks of the Seine, a lanky silhouette, when a clock rings two in the morning. Gowns of infinite colors, like the night sky blooming into dawn.

Emerging onto the street out of the swirl of another dance club, Kuki is struck by a precipitous displacement. He is homesick for his homesickness, the feeling of an expat suddenly unsure of where he belongs. Standing on a corner, he brings an Abdullah cigarette to his lips, contemplates the rose petal on the mouthpiece, and exhales in the warmth of the dark. The smoke puff floats in still air over the all-night cafe lamps and through the beams of electric street lights. It dissipates as it ascends, joining the gray blanket over the city.

Life exists in such contingent moments that are lost as they pass. There is something, and then nothing again. Then the scene repeats:

Night has come

To Montmartre

Where people run into each other:

Blue heart,

Red lights.

III. AN INVIOLABLE DIGNITY AND GRACE

Before he returns to Japan, Kuki begins a treatise on an idea that has become dear, something that could finally mark the exact distance between himself and his adopted European milieu, that resolves the native Japaneseness, the restlessness, he carries with him. His obsession is iki, a word for a kind of ephemeral, urbane stylishness found most readily in 19th-century Tokyo’s elite. The word might be translated as “chic” or “charm,” but to Kuki’s mind it is a radically Japanese aesthetic value, even a philosophical pose in itself.

Later in 1929, Kuki moves to Kyoto as a lecturer. His older colleague and mentor Kitaro Nishida had recommended him for a teaching position at Kyoto Imperial University, where Nishida was at the center of what becomes the Kyoto School of philosophers. The Kyoto School seeks to reconcile eastern and western ideas, particularly melding Nietzschean nihilism with Zen-Buddhist nothingness. They pursue a kind of harmony, but Nishida is adopted by the Japanese government to provide justification for its increasing nationalism: Nishida eventually argues that the particular qualities of Japanese Zen, even its peacefulness, may have to be defended by military force. Wandering the ancient city, which was the nation’s capital before Tokyo, Kuki is also reminded of the depth of his culture.

In 1930, Kuki publishes The Structure of Iki, his masterpiece. He is 42 years old. The essay applies continental philosophy to express what makes iki—in Kuki’s sense—the bedrock of Japanese aesthetics and identity. The essay defines iki, or rather summons it: Kuki catalogues what gives him a sense of the quality. Sheer fabric; a woman just after bathing; smiles in minor key; willow trees and slow, steady rain; informal hairstyles; a beckoning hand that is bent slightly; vertical stripes (as opposed to horizontal); forms that assert duality (all things at once); gray, brown, and blue hues; subdued lighting from paper lanterns; and the dance of attraction and distance, pleasure and pain, between men and women. Iki is positional, dependent on dynamic relationships and the merger of opposites: “a trace of seductive and ingenuous tears behind a charming lighthearted smile.”

Kuki uses phenomenology to apprehend a singularly Japanese sensibility, one that he feels foreigners can scarce understand—attempting a grand theory through an unabashedly personal lens. He tries to provide a diagrammatic framework for ambiguity itself. In the essay, analytical abstraction gives way to pure sensation only to veer back into abstraction. Iki brings together the checked white-brown cloth Kuki remembers from his mother’s kimonos with the tease of Parisian burlesque. It comprises the melancholic and the erotic: “an inviolable dignity and grace,” an unwavering commitment to this stylishness above all. Perhaps it is style as an ideology.

Key to iki is resignation. Not reneging on desire or embracing asceticism but resigning to loss: of relationships, for example. It might be better to dream of ambiguity than experience the reality of possibilities collapsing. In 1931, Kuki’s mother and father both die. He and Nuiko divorce. Japan invades Manchuria.

Kuki is named associate professor at Kyoto Imperial University. The semesters are full of lectures on contemporary French philosophy, on literature, on contingency. He has swapped Paris for Kyoto’s Gion, the medieval bar district, liquid with sake and geisha, where his mother was rumored to have once worked. He tries to focus on his academic work and his growing reputation, penning essays and casual articles for publication, but history intrudes.

In 1936, a student of Husserl and Heidegger named Karl Löwith, of Jewish descent, writes Kuki a letter requesting help in finding a position in Japan so that he might escape Germany (Heidegger joined the Nazi party in 1933). Kuki arranged a post for Löwith at Tohoku University, though he was later forced to escape once more when Japan allied itself with Hitler.

In 1939, Kuki travels through occupied Manchuria as part of his duties as a public scholar. He regrets the trip; it’s an arduous responsibility. With fascism ascendant in Germany, Italy, and Japan, Kuki is split once more between his desire for a deep Japanese identity and his cosmopolitanism, the awareness that difference and distance are what create aesthetic interest. What does an aesthete do at a time like this? On good days Kuki feels he is working to preserve something important for the future, adding to humanity’s storehouse of philosophical knowledge and cultural memory; on others he thinks he only immerses himself in nostalgia for the past to find comfort. The aestheticization he espouses also clears the way for militarization: Japan’s sense of threatened uniqueness propels it toward war.

As the tumult rises, Kuki’s thoughts constantly slip from extreme nationalism and war to the ethereal abstractions of philosophy and his European sojourn. The ephemerality of those few years in Paris, its easy attainment of iki, makes it beautiful, and perhaps all the more beautiful in mind than reality—if he had stayed there, say, and left his Japaneseness behind. He might have made such a choice. Kuki’s aesthetics are ruthless in that regard: When you have money, you must be willing to spend it all. When love ignites, you let the flame burn and then gutter. When a moment ends, it is gone. One must resign oneself to this in order to find and accept beauty. In June of 1940, the Germans occupy Kuki’s beloved Paris. It seems impossible, but what is he, a devotee of detachment, to do about it?

A sudden, implacable attack of fever and cough like a spring cold—on April 10, 1941, Kuki is hospitalized and diagnosed with peritonitis, an inflammation of the tissue covering the abdominal organs. On April 29, he writes a poem to a friend thanking him for a sickbed gift of potted azaleas. He observes the flowers at their peak, “Dimly blooming / A thin red.”

On May 6, still in the hospital, Kuki dies. He is 53, not young, but not old for a philosopher, one whose work had always been in front of him. Kuki leaves behind so little—a few black-and-white photographs and the accumulation of his writing and ideas, intricately structured but always edging toward their own dissolution.

Kitaro Nishida translates Goethe’s poem “Ein Gleiches” to inscribe on Kuki’s tombstone placed on the cherry tree-lined canal of Kyoto’s Philosopher’s Path, which the two walked together many times. The lines reflect the peaceful nothingness from which everything emerges and to which it returns.

Mountaintops appear in the distance

No wind makes the treetops sway, no bird sings

Wait a moment; in the end, you too will be resting

IV. MEMORIAM

Aesthetics are always political because nothing is inextricable from politics. Art often has an unwitting or unwilling role to play in moments of crisis; what it can’t do is stand completely apart. Attempting this impossible isolation can be even more dangerous. “The logical outcome of fascism is an aestheticizing of political life,” Walter Benjamin writes in 1936’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. “All efforts to aestheticize politics culminate in one point. That one point is war.”

Seen in retrospect, Kuki Shuzo’s life and philosophy constantly drifted away from the political events of the time. He failed to make a stand against his country’s insurgent militarism and the war that followed. His meetings with Heidegger tainted Kuki’s place in the academic record; scholars today comb through his work for signs of fascism or ultranationalism. And Kuki is vulnerable to such critiques. Even as his stated ideals, particularly in Paris, run counter to absolutism, he still assigns his aesthetics to the Japanese people alone as a marker of homogenous identity. At times, he worked to aestheticize politics.

We now live in another moment of mounting fascism and violent clashes of national identity. Rather than seeking spaces of sympathetic ambivalence—the committed cosmopolitanism of Kuki's life and the sensual uncertainties of iki that he makes clear—difference seems to be the only thing that matters. Identity is zealously guarded and boundaries reinforced instead of crossed or softened. In this context, Kuki’s relative escapism and his belief in indeterminacy feel like a balm, a reminder of “possibility as a possibility,” as he once wrote, though his later life did not necessarily bare this belief out.

Better to take from his story what is valuable and notice the potential for an aesthetics that resists hard boundaries, that exists in the ambiguous spaces between things, that is always moving away from the simple definition. This is also a form of resistance.