On Knowing Your Shot Is Good

Hanif Abdurraqib

June 18, 2018

It is a blessing to know your corners and angles. On any court this is true, but on a home court—one that is yours—this is especially true. My home court was in Columbus, Ohio and rested in the middle of the Scottwood Elementary schoolyard, at the center of an otherwise nondescript playground. The rims and nets on the hoops were refurbished in the middle of every spring, whenever the first warmth broke over the concrete. New nets were added to each rim, and each rim was straightened to its normal angle, after the previous summer and fall had taken its toll.

If you are from anywhere deemed the hood by those living inside of it, you might have a space like this. Some place gently cared for amidst what might seem to others like a mass of ruin. The basketball courts at Scottwood Elementary were this place. Looking back, it is hard to tell who did this labor or why—if it was the school, or just someone passionate about the neighborhood, who knew what the courts meant to young people in the late spring and all throughout the summer.

If you have game you might know what it is to desire the net hanging from a rim, and no one who has game wants to play on anything without a net, for the way the ball sounds when it dances through, for the small choir of dust that kicks up and kisses the air after the ball rolls around every inch of a net, for the way the net, when really hit right, flips upside down and must be untangled from itself.

All of these things are a type of glory that those who have game understand. The people who played at Scottwood Elementary had game, but no one had more game than Estaban Weaver, who was not from the Eastside, but would come out every now and then to put on a show. And if he came out, the rest of the hood came out. All of the best shooters, all of the big men, all of the high-flying dunkers.

As a kid, it was like watching the NBA up close, perched with my pals on some playground apparatus, or on the other end of the baseline, dribbling the half-inflated balls we’d picked up from the back of someone’s garage. We’d watch Estaban spin through traffic and put up impossible shot after impossible shot, wondering how anyone could hang in the air that long and ever want to come back down to earth.

*

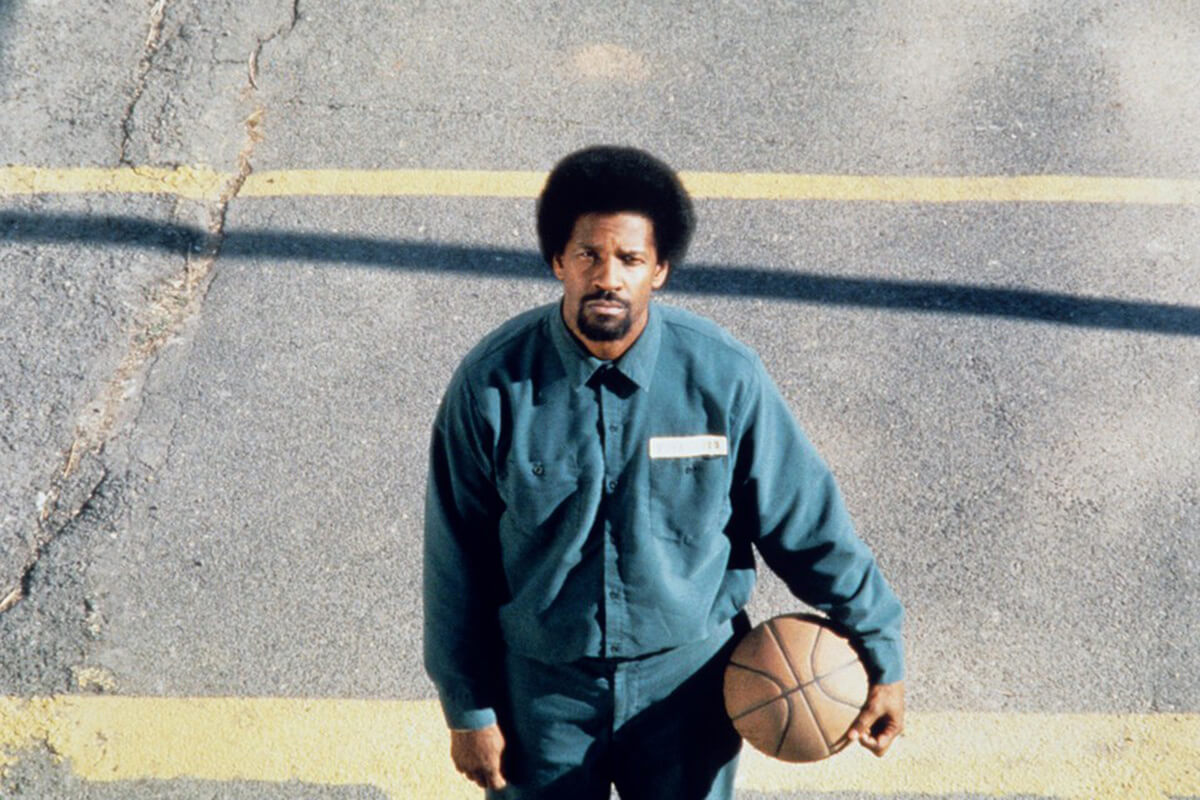

Ray Allen can’t act but that doesn’t matter because the viewer knows they aren’t watching the film for Ray Allen the actor. Ray Allen was pretty much playing himself when Spike Lee dropped He Got Game in 1998. The story is only kind of about basketball, and largely about the relationship between a high school basketball phenom and his father.

Jesus Shuttlesworth, the basketball star, is living on his own in New York, raising his sister while his father, Jake, serves a sentence for accidentally killing his mother six years earlier. Jesus is being courted by every major university, and the Governor of New York would prefer that Jesus go to the fictional Big State University. To aid with this, he grants Jake a temporary release from prison to try and sway his son in the direction of Big State, with the idea that if Jesus chose the school, Jake would be granted an early release from prison.

What the film does well, beyond anything, is incorporate basketball in a way that seems real. This is, in part, because many of the actors were basketball players themselves, just playing the game for the camera. Walter McCarty, Travis Best and John Wallace play Shuttleworth’s high school teammates, making for a beautiful on-court magic in scenes like the one at the start of the movie, when the team engages in a full-court pickup game which feels like it could be a game played in your neighborhood or mine, or any one where the streetlights come on above a court and stretch the night out a bit longer than it was expected to go.

Yes it is true that Ray Allen cannot act and it is perhaps a lot to demand such an emotional role out of him, but the work of Denzel Washington as Jake Shuttlesworth is so strong and enduring that it almost drags Allen up to the level of a star actor. We are shown the scene where Jake kills his wife, and so we know—despite it being an accident—that he was at the very least abusive. The work of the movie isn’t necessarily to make a viewer feel for Jake, but perhaps it is to get a viewer to feel for the distance between Jake and Jesus, knowing the gap between a dead parent and a living one becomes more raw when the love for the living has faded away.

*

After my mother died, it was my father who came to every single sporting event, no matter where in the city. My father was not an athlete, and therefore, I don’t have any stories of him teaching me any skills I acquired in any sport. My father did not have game, but my brother and I did, and there’s no real telling where it came from. We maximized our potential in sports other than basketball—me soccer and him football—and during our high school years, our father would drive across the city, sometimes from practices to games, never missing one.

I never resented my father for not teaching me how to shoot a basketball, but I’m simply unsure how that information arrived to my body. There are mechanics to the proper jumpshot: the ball leaves the tip of a shooter’s longest finger last, to ensure the highest point of rotation, so that when the ball arrives at the rim, it has spin on it, hopefully allowing it to sit on the rim a bit longer before falling through.

Estaban Weaver’s harshest critics would say he couldn’t shoot—that he was all speed and first step and not much else. But in remembering now, I think I learned the mechanics of the jump shot from him. The way his came at the height of his jump, with a sharp and quick wrist flick punctuating the motion. The shot didn’t always go in, but it almost didn’t matter, the way a rainbow sometimes touches down inside the heart of a majestic skyline and sometimes falls over a landfill.

Before I was old enough to step onto the court at Scottwood with the older players, I would come out in the afternoon with my friends and try to mimic the jump shot I’d seen Estaban take time and time again. I’d miss over and over, but hold my form steady, watching the ball careen off the rim.

*

The central moment in He Got Game rests at the conclusion. After spending much of the movie attempting to bond with his son, Jake finally agrees to play Jesus one on one at night, on a court lit by streetlights. If Jake won, Jesus would attend Big State, the way his father had been pushing him to. If Jesus won, Jake would be out of his life forever. It is the moment the entire movie has been building towards.

Earlier in the film, there is a somewhat tender scene between the two, walking on the Coney Island Boardwalk. Jesus asks Jake why he got his name, lamenting the biblical aspects of it. Jake, taken aback, explains to Jesus that he was named after New York Knicks guard Earl Monroe, who had the nickname “Black Jesus” early in his career, before the media got hip to him and changed his nickname to “Earl the Pearl.”

The scene is touching because it is one of the few in the film where you see Jesus softening to his father, watching with faint joy as Jake mimics the legendary Black Jesus. Jake was once a great basketball player. We are to understand this from the start of the film. Jake had game, unlike my own father, and he passed the game down to his son, who at the end of the movie stands across from him at the top of the key.

Jesus was always going to win. Jake is smaller, older, less athletic. And yet, as the game begins, Jake takes a brief lead over his son. But it is short lived, with Jesus removing his jewelry, deciding to take the game more seriously. He dominates his father, ending the game by dunking on him, and placing the ball on his fallen father’s chest.

While gathering his things and walking off the court, Jake turns to Jesus and tells him to get the hate out of his heart. The last thing the father passes down to his son. Jesus ends up at Big State, but the Governor decides that Jake didn’t play a part in his choice, so he remains imprisoned. But his son, he imagines, is freed from his own inner turmoil—the anger he’d harbored towards his father.

*

There is no way to describe the feeling of a shot you know is going to go in before it goes in. It is especially difficult to explain this to someone who does not have game, but here is how I will try: the ball leaves your hand and your hand itself feels the caress of the net the whole time. The ball leaves your hand and the wind whispers thank you to the spaces in between your fingers. The ball leaves your hand and the ball longs for touch as it spins through the air, reaching backwards for its old home.

We all have our spots, those of us with some game. Mine is just to the right corner of the free-throw line. I know I’m money from there because Estaban Weaver was money from there. The thing is, if they fear how fast you can blow by them, a defender might play off of you, and so you’ve got to be able to hit a shot from somewhere. That was Estaban’s shot, and so that was my shot, perfected after hours on the Scottwood blacktop, copying his form.

And of course, if you are reading this, you will maybe know that Estaban Weaver did not make it, because you would have known the name from the moment I first offered it to you. He was the subject of a recent documentary that hit it big in Columbus, but was never the NBA star so many saw him destined to be.

If you are reading this you will know that I say “make it” and mean make it out of the hood, or to the league, or to anywhere one might be able to pay for comforts their parents could never afford. Estaban Weaver was a high school phenom in ‘90s Ohio. LeBron James before LeBron James. But he switched high schools too many times. Fought with too many coaches in college. Kept too many dealers in his entourage. The league stopped calling by the time he was on his second college.

In He Got Game, we never know if Jesus Shuttlesworth makes it. We see him in college, but beyond that, his fate is unknown. Maybe he got kicked out of school. Maybe he couldn’t make the grades or maybe he failed a drug test. I know what making it means, but I also know what He Got Game means when it defines what making it is: being at peace or having your name be an echo or loving the people who come from where you come from.

No one plays at Scottwood Elementary much anymore. The golden days of Eastside Columbus basketball ended in the mid-2000s, and so whoever refurbished the court each year stopped coming. Every now and then, someone will do a shoddy job of hanging a net up on one of the bent rims, just for the small handful of neighborhood kids to play on from time to time.

When I visited my old neighborhood in 2016, I went to the courts and saw a net loosely hanging, a half-inflated ball resting at the foul line. I let off one jump shot with the form I learned from watching Estaban Weaver, who lives at home and is still a legend. Who takes care of his mother and still dominates summer leagues. The ball slurped through the torn net, whispering his name as it went through.