Measured Life

Alex Ito

November 19, 2019

When I was growing up, my grandfather wore an American flag pin on his red baseball cap. He was a character—always playing pranks and making faces to entertain his nine grandchildren. He was also pensive: religiously mowing the lawn, crafting home fixes with popsicle sticks and tape, hiding cash around his home and meditating in his white plastic chair with a cigarette embering between his fingers on a hot Los Angeles day.

I was only 15 years old when he and my grandmother passed away. But I’ll always remember that American flag lapel pin, shining so distinctly against his sun-bleached cap. One day I asked him why he always wore it. He said, “It’s so if they ask, they know what we are.” His answer was vague but settled, and even at my young age I knew who “they” were and why this interrogation was on his mind.

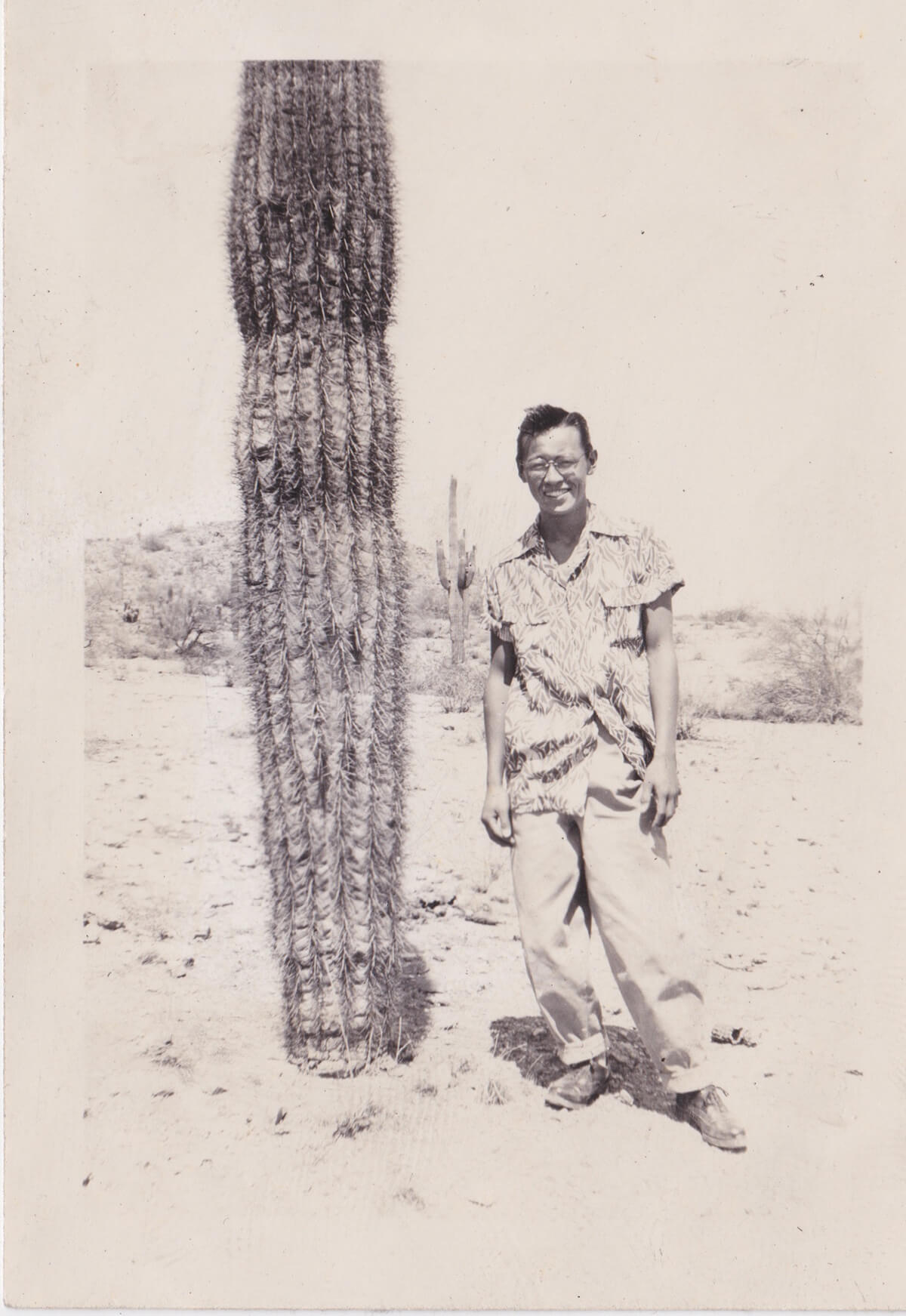

My grandparents were among the 112,000 Japanese-Americans incarcerated under Executive Order 9066. Evicted from their homes in Los Angeles, they were relocated to Gila Bend and Poston, Arizona. There they were greeted by guard towers, barbed wire, and the dusty, unforgiving isolation of the desert. In 2017, while on a research trip to the internment site, I stood atop a hill where my grandfather would sit for hours as he was assigned to “guard” the water tower.

Looking towards the rippling horizon, I imagined him in his early 20s—in the scorching heat, another cigarette between his younger fingers, contemplating the never-ending geography of the state; his body, a prisoner of the state, left to crumble into dust. The state was They. The lapel flag pin and red hat acted as a small but necessary precaution for his own preservation. Today, when I think of a red baseball cap, another image occupies my mind.

Recently, I came upon drone images of a migrant detainment camp on the US/Mexico border: chain-link fences, bodies corralled in makeshift shelters no different than dog kennels. “How could they think we would never see this?” I asked myself in disbelief. After letting my nerves simmer down, I understood the flaw in my question. In that moment, I never imagined the abolishment of the migrant camp, but merely for it to be humane, clean and acceptable for my imaginary standards of carceral practice. My eyes were, for the moment, blind to any other future.

What does the state do with the bodies they consider a threat but cannot lawfully, or ethically, destroy? Migrants, prisoners, the religious other, the poor—these bodies are deemed social waste by administrations around the world. But this is the 21st century, right? We are aware. We are developed. We are humane. This distinguishing of the humane within social-waste practice is laughable, concerned more with the optics of ethical practice rather than the radical shift in program. You cannot develop humane practice without recognizing what is human. In the case of marginalized bodies, the scholar Alexander G. Weheliye said it best: “We never were human.”

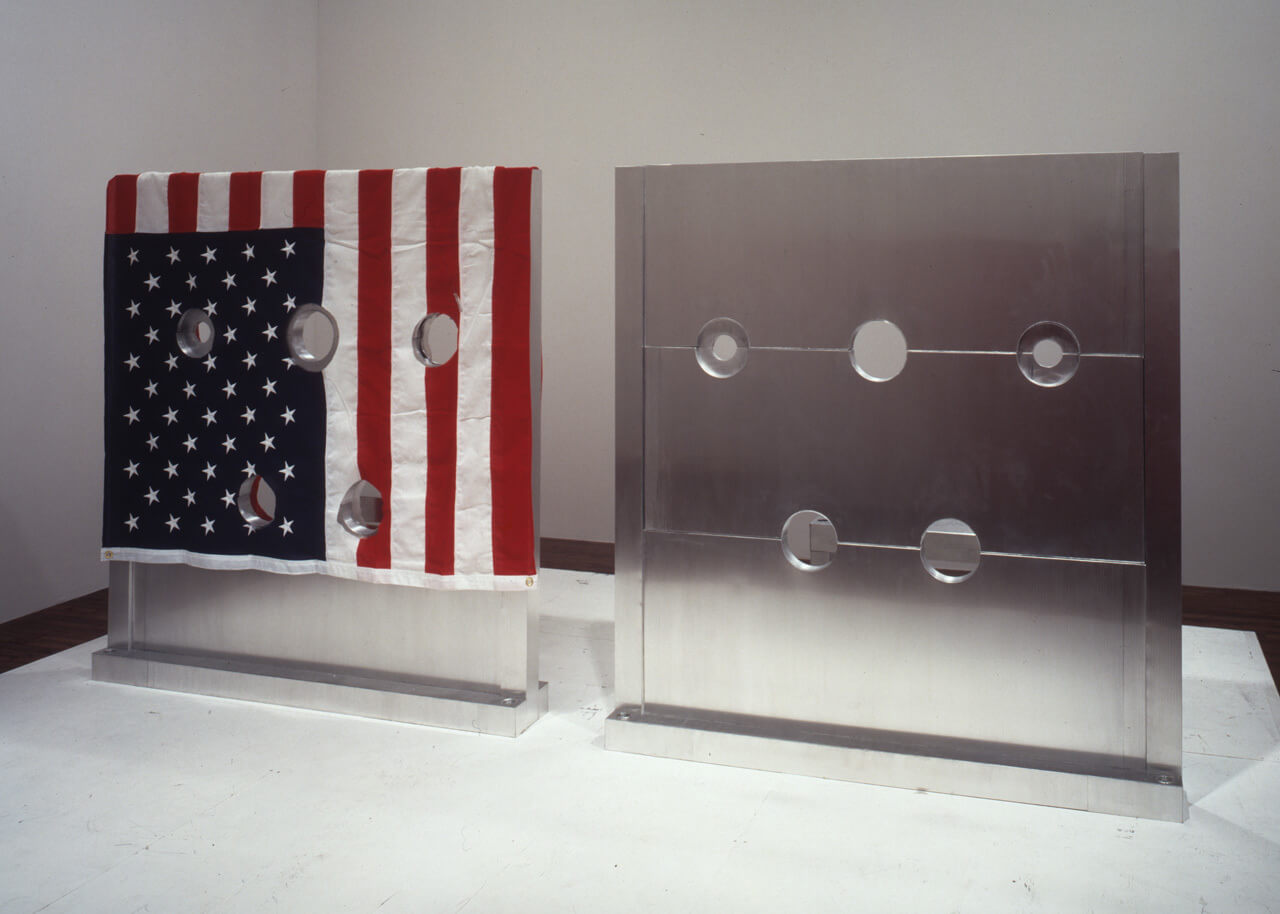

Forms of invisibility as cultural disposal are inseparable from American history itself. From the Indian Removal Act in 1830 to Jim Crow, from Japanese internment to today, these forms take on a peculiar and specific shape, one that emphasizes the carceral practice of segregation and “lawful” imprisonment over the infamy of annihilation. Out of sight, out of mind. Invisibility becomes the characteristic of the humane. Violence is enacted, but as a soft violence—delegated in legislature, reinforced through social language and conveniently segregated within the all too visible margins. The violence is public, woven into the fabric of everyday life through painted signs, razor-wired fences, and our social-media feeds.

In the haze of screens, violence has taken on a new form. Its documentation has become as ubiquitous as images of pets or food porn. We are rarely alone, both surrounded by and surrounding others through the ambient presence of current events and biopower. Pain has become linguistic currency, a media spectacle energized by the urgency of social-political action. The stream of violent information carries blood alongside leisure as the current hastens and the self dissolves into minor moments in a scrolling attention.

Life has flattened into viral images, instantaneous and impermanent. This practice of rendering, now reduced to a quantity of functions and values, becomes the methodology in question to call upon a familiar ontological inquiry in order to further understand the implications of these practices: How do we measure life?

“The ‘being’ of life is itself constituted through selective means; as a result, we cannot refer to this ‘being’ outside of the operations of power, and we must make more precise the specific mechanisms of power through which life is produced,” Judith Butler states, meditating on how life is recognized, framed and thus gifted or denied our grief. However, this discussion of recognition is complicated when we take into account not only the operations of power, most often held by administrations of the state, but the action and inaction of the networked viewer, a proliferating techno-gaze in which data is available and yet conveniently phantasmagoric in an age of digital transparency.

But what becomes now of the lives of invisible communities: the imprisoned, the occupied, and the forgotten? On our screens, we see the detainment camps and the tear gas on the border of the US and Mexico. We see the increasing annihilation of Palestine. The brutality of police and the growing death toll of black bodies has become an everyday affair. The precedents of an oppressive history and its ever increasing weight are embodied within the lives of the public; like my grandfather and his flag pin, granted back his life but as state property, an ex-agent of fear in public population.

Witnesses to these atrocities remain plentiful, yet borders remain closed, ICE grows, far-right governments win elections. What I ask is not a question of whether we, the viewers or witnesses, care. I ask how life is framed by the multitude in the terrain of an undeniably public violence while that same life—the physical body and internal spirit within the power-machine—becomes invisible in plain sight on a massively public scale.

*

The issue lies within the facade of the humane. To deem an act humane, one must recognize life as a constitution of being human and the ethics of such. For example, a biological human should not be subjected to unlawful death or disposal. However, to enact a policy of invisibility, one does not need to grant life recognition because life does not need to be regarded with care, if justified by law, although it remains physiologically alive. Thus, a state that openly does not care for others can advocate for the preservation of life and still deny it in the public sphere. Through the guise of humane policy, a bloodless war is waged against the vulnerable as they are coerced into public shadows—a space of merciful incarceration absent of care.

And the spectator is never innocent. Within a space of transparent communication still resides the specter of enmity that greets us into our shared panopticon. A real life Hunger Games takes place amongst the world’s dispossessed and furious. But policies of invisibility, as viewers and citizens become socially leveled by the functions of a networked age, permeates from legislative power to the amorphous and mutative social language of the virally shackled multitude. We become the keepers of our own violence.

The philosopher Byung Chul-Han warns of total transparency—the ubiquity exposure and the accessibility to our private information—its agenda to progressively vacate human beings of negativity, and its eradication of necessary otherness to shift towards a “dictatorship of the same.” Without the ability to evade calculation, life becomes further entrenched to the powers of the administrative machine, less available to define itself intimately or be regarded as such.

What is lost is a necessary difference—the coyness of being that is less intended to allure total understanding but to merely recognize its very existence. An accessory with hypercommunication, hyperinformation and hypervisibility, it is impossible to see the violence of transparency outside of modern technology and the frameworks that are produced by such media. It is this transparency that reframes how life is experienced in everyday life as life becomes distanced further from intimacy and even recognition.

Well before the 2016 Election, forms of violent camaraderie plagued the more fringe corners of the web. Take #Gamergate, where developers Zoe Quinn, Briana Wu and feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian were threatened and harassed because of their advocacy against the misogyny of the the gaming community. Quinn received multiple death threats and hacking incidents and Sarkeesian had to cancel a lecture at Utah State University because of multiple threats. Such violent coalition speaks for itself—a force of individuals swarming at the threat of their favored hegemonic system being dismantled. Anonymous and elusive, the viral spread of hard violence— physical and direct harm against the body— is easy to condemn yet difficult to monitor.

In this account of #Gamergate and right-wing action, the self is rendered invisible not only by state powers but by the networked hoard. What surfaces is the cruel disconnect between users, the fading opportunity to rehumanize and reclaim a body turned capital. A unique form of alienation occurs under the conditions of our prevailing attention economy. Templates for self-individuation by social media further entrench the user into codification and representational value systems. This produced hyperself is the new-age flâneur drunk on the post-humanist nightmare; granted the seemingly unlimited access to information, but barely free.

But are the offenders only those of a visible and historically threatening hard violence? More and more, online spaces have become the new theater of enmity—engaging not only the right-wing spheres, but those which align as liberal and progressive. As right-wing politics continue to rise, the urgency to combat those forces becomes increasingly more important. Racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and sexism need to be eradicated from this world, and those who subscribe to such ideologies need to be dealt with. But how do we deal?

I think back to the January 2019 confrontation between Nathan Phillips, a Native-American elder, and Nicholas Sandmann, a Covington High School student. The most virally shared part of the confrontation was when Phillips, playing an instrument for a sanctioned protest during Indigenous Peoples’ Day, stood face to face with Sandmann, smirking in front of his chanting classmates, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

The video quickly went viral, spreading to news and social media outlets. Many viewers sided with Phillips, expressed solidarity with indigenous communities and standing against hate groups. But some called for violence against the 16-year-old Sandmann. These reactions resonated with the threats seen during #Gamergate, with the lives of individuals being exposed online for the sake of potential, albeit potentially uncommitted, physical harm.

The Phillips-Sandmann confrontation and #Gamergate come from different sides of the political spectrum but occupy the same violent imagination disguised as social potential. On one side, violence is used as a method for preservation: to uphold existing frameworks of oppression in specific communities. On the other side, violence is instrumentalized for sociopolitical change—to rid the world of communities endangering the lives of others. The threatening individuals involved with both are committed to their own ideation of a narrative unfortunately executed through the proposition of violence.

In an age of transparency, community thrives in movements like the Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, as well as, inversely, the Proud Boys and other representatives of the Alt-right. Collectivity and accessibility have become the hallmarks of the digital commons, while discourse occasionally dissolves into individual and collective grief and rage.

My intent is not to disregard the pain and anxieties of others. What I want to address is how we frame the lives of others we encounter in the sphere of enmity, and how the proposition of inflicting pain onto others resonates with existing invisible policies embedded in fundamental functions of the state. These questions not only concern what it means to cope with an adversarial individual or community, but also what one is asking for when they call to be “without” that adversary. These forms of elimination can take on varying forms ranging from social isolationists to a detention camp.

Although I recognize that these may be false equivalences, there are still elements to analyze when we determine something to be put out of sight—demarcating our own spheres of existence as exclusive to others and to what degree we imagine such exclusion. What I speak to does not demand that we all have to exist with each other, for there are varying histories and traumas that justify such apprehension, but that within the realm of pulsing bodies and an unforgiving historical record we must analyze the imagination of being-without in relationship to “humane” policies of violence and erasure.

In both #Gamergate and Sandmann-Phillips incidents, life becomes data—a currency of exchange in a transaction of violence. This abstraction dangerously becomes disguised as a form of political action. We should eradicate bigoted ideologies, but we should not bolster the power to violate human life.

We’ve seen practices ranging from Native American reservations, Japanese internment, and migrant detention camps as “humane” methods to dispose of social waste—an optics of care that simply means anything less than capital punishment. But annihilation inhabits the frameworks in which everyday language becomes weaponized and redistributed. The disappearance of life, or the act to render it invisible, resides in both the practices of the state incarceration and in our social media feeds. We are fully encapsulated in a world of incognito enmity, clad in the facade of an equal society.

When reflecting upon the public utility of violence, I refer back to Hannah Arendt’s meditation on the relationship between power and violence. “Power is indeed the essence of all government, but violence is not,” Arendt says. “Violence is by nature instrumental; like all means, it always stands in need of guidance and justification through the end it pursues.” The instrumentality of violence for political ends calls upon the user to enhance and justify their desire for violent action with ideology. This is why in many cases violence accompanies power, but Arendt asserts, “Violence can always destroy power, out of the barrel of a gun grows the most effective command, resulting in the most instant and perfect obedience. What can never grow out of it is power...To substitute violence for power can bring victory, but the price is high; for it is not only paid by the vanquished, it is always paid by the victor in terms of their own power.”

The desire for universal order and power lacks the tools to consider what Felix Guattari called the “mutant universes of value.” There is a harmony in this chaos; a chaos of heterogeneity, apprehension, vulnerability and learning. It is yet to exist in public practice, but resides in the desire for a world that expands the rights of others rather than diminishing them. However, to begin such change across communities and to reform policy, the work must first be done between individuals. Alone and together, we must divest from the functions of competition and cruelty that fuel state violence.

When my grandfather was released to the American public he did not immediately put on the red cap and flag pin. He bought a zoot suit and raced hot rods. When asked “loyalty questions” by the War Relocation Authority, he refused to submit his life to the American armed forces and stated he would not die for this country. Refusing violence is a powerful action, no matter the scale. Refusal is the Italian unions declining to load Saudi Arabian ships as protest to the war in Yemen. It is the protests to remove leaders like Trump, Bolsonaro and Rosselló. It is exposing a museum board member for their involvement in weapons manufacturing. It is punk, grassroots movements, and DIY venues. It is protecting kids from racism on the NYC subway with a cup of soup. It is love. It is a form of persuasion that opens an inclusive dialogue for others; to escape the ubiquity of submission and, for a rare moment, to be seen and perform action in plain sight as an agent of life.