The Psychoanalysis of Panic

Jamieson Webster

July 16, 2019

Even as panic is one of the most isolated, internal, and extreme, individual experiences of fear, it is also completely contagious, like girls in a boarding school reading a break-up note all-together. Panic has everyone in a panic, even when panicking about panic can be whispered in humor: Trump panic, climate panic, health-care panic, border panic, stock market panic, trans panic, sex panic, socialism panic, the list could go on.

I started to dream of panic night after night, perhaps in order to write this text, panic making a joke of itself even as the experience is anything but funny. The dreams left me so tired. Some psychoanalysts, God help me, think that panic is suppressed tears, or laughter, or both. Maybe that’s not wrong. In any case, you still have to ask yourself what is so heartbreaking, or heartbreakingly funny.

The first dream, a few weeks ago, I was staring at a hoard of animals, their beating feet plowing through the earth as they crossed vast terrains of fecund nature, not pastoral nature, not an English garden mind you, but nature that is primal, death-bound. Why is this image so anxiety inducing, as if it mimics the racing of one’s heart, the sound of a body meeting with the earth that opens up around it? It’s also an image of war. I then find myself in some building opening a door to Anna Wintour and that cold stare of hers; her name a reference to the winter zombie apocalypse in the much-anticipated season finale of Game of Thrones.

Is it so embarrassing that I’m watching this? I have a 15-year-old. Watching the anxiety fueled battle with the dead that can’t die, he attempted to micromanage it from our couch. I found this rather amusing given that it’s a fantasists’ series. “None of this real,” I yelled at him, “it doesn’t matter if they set the trench on fire in the right way.” He laughed. How do you kill something that’s already dead? The question is more interesting than the show, to be sure.

Back in the dream—Anna Wintour enters the room and inspects me like an insect, only to turn to the carpet which captured her ire more than I did, because what do I matter, she then belting out to the staff the inadequacy of what she found herself standing upon. Why isn’t she anxious? Why isn’t this inspection of hers a sign of her own panic rather than her power? Isn’t it?

Suddenly, my boyfriend and I are sitting together in the office of the principal, two chairs lined up before her desk—I never sit in front of people who sit at desks—and it’s all rather unclear who is in trouble: our child, or ourselves. We are too old, he reminded me in the morning, to feel in trouble; we are, but you are never too old for this kind of panic, or at least not too old for the memory of it. In today’s panic-stricken environs, these kinds of early memories of anxiety are too easily tied to reality. Perhaps we can resolve this panic as nihilism or cynicism?

Next dream: I was beset by an image of garbage-filled seas, and was watching the last penguins on earth—somehow that’s made clear to me—their little black-and-white bodies being bashed by the waves, or, having had a last joyous moment in the ocean they are now being washed up on shore. “They will not return,” someone says to me.

This whole dream is some elaboration of a meme I saw on Instagram before going to bed where a woman hands a man a fish, and he asks for a plastic bag, and she says, “it’s already inside.” The caption for this particular meme was: this meme just shit on the entire planet. Or was it, this is a meme of how we shit on the entire planet? Forced to waste more time and go look it up—No, it was the first. What does that even mean—this meme shit on the entire planet? I think my unconscious was interested in what the fishmonger said—It’s already inside.

The dream comes to an end with an image of the purest anxiety—the transformation of something into nothing, pure diffusion or dissolution. The bodies of the penguins evaporate into a black-and-white substance, something that can now come out of a pen, ink on paper, the image produced some kind of a sonogram, some indication of what is on the inside—a pregnancy fantasy to be sure, but also a joke much better than the Instagram one simply because it’s an unconscious joke on me about penguins, pens, penis, ‘penic’ as having to write or give birth to this text on panic. The etymology of ‘pen,’ just in case you were wondering, is to add, to weigh, to weave. In other words, another name for Webster. I gave birth to my own fucking name. Great.

For Freud, pregnancy meant giving oneself over to the needs of the species, sacrificing one’s individuality, inviting the reality of death; you become an appendage to your own creation, which, in any case, is going to leave you, will most likely survive you. Procreation is division, evaporation. It’s the opposite image to that of pollution where we claim the earth as ours and ours to shit on, as we imagine that we will survive it. Internalization is both a figure or pregnancy and a psychic achievement—take it inside in order to get out of yourself. I’m tired of your grand metaphysical claims. Your Freudianism is tireless. Penguin soup is hardly a grand metaphysical claim? I’m sorry I always want another baby. I’m sorry that I can’t figure out what is already inside. I panic less than most of you.

So finally it’s the weekend, I still have to write this text, and that night I let out a small scream, woke up Charlie Brown who was sleeping soundly beside me, only to explain to him that we were about to hit a bus with our car, T-boning it, as they call it. He had told a story recently about an accident in Italy where someone T-boned a car in their motorcycle—I put myself there where I wasn’t, and yes, I’m well aware of the sexual innuendo in this term. In the dream, and this is the unconscious kicker, we T-boned the bus after I was given the drug Buspar, supposedly to help me work. Google it, I pleaded with him after I woke up. I think it’s heart medication.

Buspar, Busperon, it’s an anxiolytic, it’s for anxiety, he said. Hilarious. Yet another unconscious joke on the heels of panic, this one about ‘bus’ and us and dying and writing this text. But we didn’t die, he said to me in the middle of the night, we flew over the bus and into the Mediterranean sea. Everything is fine. I’ve never been to the Mediterranean, I said to him. I was in school for 30 years learning how to deal with other people’s panic. What kind of a life is that? You can see what a pain in the ass I am. Pain is an anagram of panic minus the c. Please, let us go to the sea.

*

The origin of panic is the god Pan, the wild Satyr, half animal, half man. But before the goat-god, a little Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. What is now called Panic Disorder—or its singular manifestation known as a panic attack—used to be called either anxiety neurosis (a Freudian term which meant you were more anxious than neurotic and included, for Freud, the phobias), or, to go back even further, pantophobia (from the 5th century) which means the fear of everything, or vain fear, inanis metus in Latin.

This fear of everything is set against specific phobias, like of snakes or spiders or driving or people, in psychoanalysis, because one is much better off when this everything can be reduced to a few things. Life is simply easier—just don’t drive or fly or get near spiders or snakes or people. This was an important psychoanalytic distinction because to be afraid of one thing gave you symbolic ground whereas being afraid of everything left one no entry point to psychoanalyze. Nevertheless, phobia demonstrates that every symbol, every object, is simply a fixation. Panic demonstrates the way in which a mind can float, fixating on a negligible passing object, only to move to the next. It says something about the drift or drive present in anxiety and the accidental, fabricated nature of what occupies our fears.

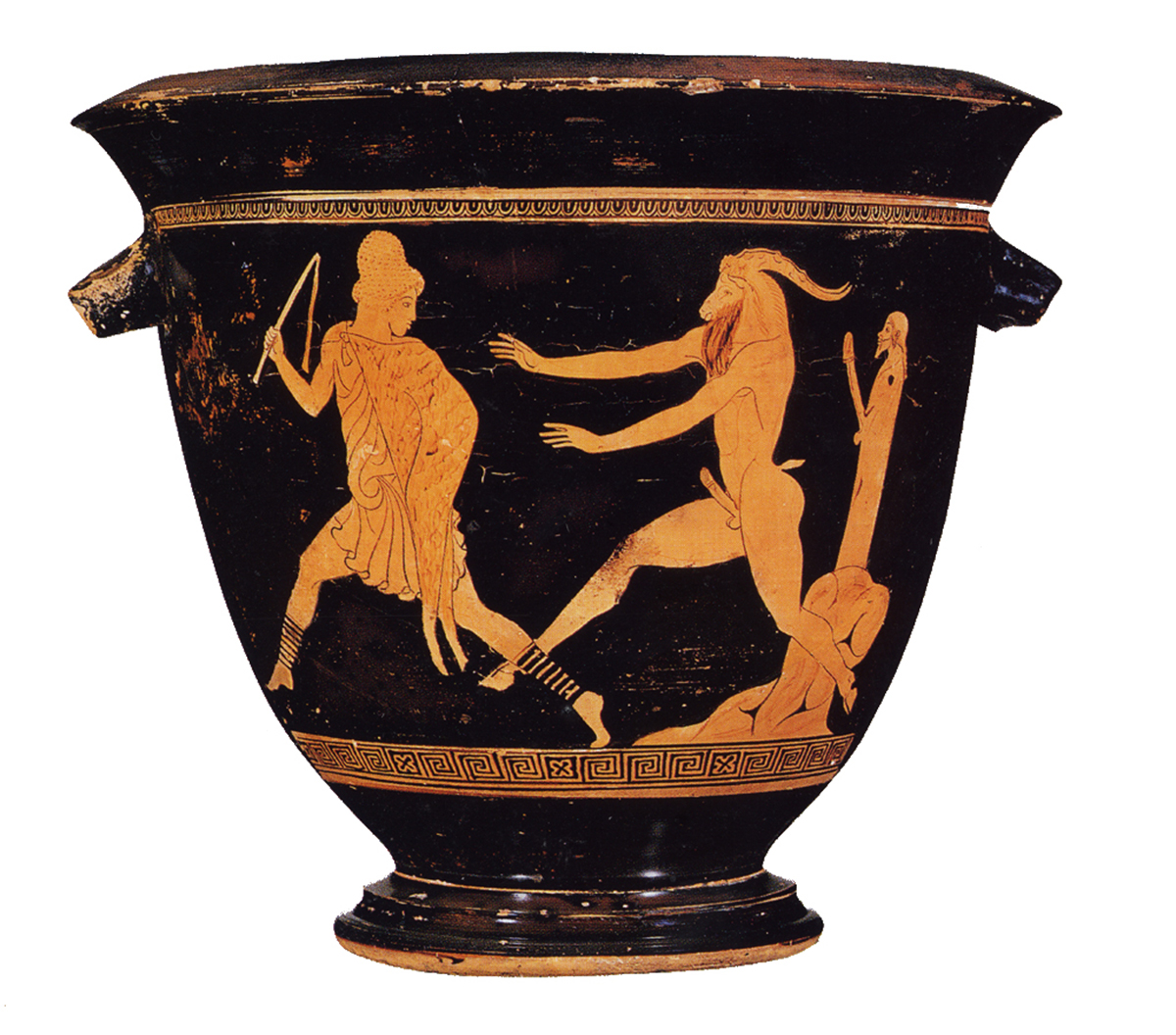

Interestingly, this fear of “all” covers over the origin of panic. It isn’t in the all meaning of pan, but refers specifically to the god Pan. This confusion between all as Pan and Pan the half-man half-goat God is apparently the butt of several jokes by Plato. Pan is wild; standing for nature as opposed to laws of the city. He was always depicted as virile: he taught Shepherds to masturbate, had a constant erection, sometimes had sex with animals. Pan-sexuality then is not only being blind to gender, but species as well. He was constantly raping or “seducing” women, though these often ended in failure and are mostly thought of as comical tales. Several of the women who Pan attempted to rape escaped his wrath by becoming flora in the model of Ophelia. One became a tree, another reeds on the shore of the river she ran across in in order to escape him. These reeds became the pipe he’s often shown playing.

Women in panic become trees becomes sound. Sound becomes Pan’s instrument of panic. The god was said to rustle bushes when people were traveling through the woods from city to city in order to induce panic. In the rigorous logic of myth, Pan plays with the foliage that represents the panic of almost-raped women in order to terrify a passerby as they step across the border that delineates man from nature, civilization from wilderness. Why, you might ask? Well, Pan doesn’t like to be woken from his nap. It’s when he’s woken that he plays this little game with bushes, or lets out a noise that induces blood curdling fear. Hence the term panic.

In the 17th century, what was known as panophobia hysterica, also called “panic terror caused by vapors,” was described as the experience of sudden fright with dramatic reactions of heart racing or “pallor” when startled by “innocuous noises or sights”—hence the term vapors. These vapors were then blown up women’s vaginas in order to quell their fears, to put their fears back in their proper place, namely, on the inside. While we are back to theme of pregnancy, the question of worry, wild sexuality, and noises that induce panic, raises to my perverse psychoanalytic mind the question of the primal scene.

In other words, the noises that wake you from sleep, what you might stumble upon that is usually hidden, this induction into the reality of sex, especially as an infantile confusion about sexual pleasure and sexual violence, and the confusion that is the question of how and why babies are made. These noises you hear, this rustling in the bushes, are also the sign of what you are excluded from, what the others are doing and subjecting you to, forcing you to be its witness.

The imagination of the primal scene includes the attempt to be where you were excluded, to be present at the conditions of your coming into existence, the moment before you were, or the last moment when you were not. This is one way of thinking about incest—the attempt to breach the barrier of the specific conditions of your existence, not just your mother’s vagina or whatever. The line must be drawn.

Melanie Klein, the mother of psychoanalysis, thought of the primal scene as an infantile fantasy of ‘perpetual parental intercourse’ and ‘permanent pregnancy.’ Your parents are just constantly fucking and reproducing. They don’t stop. You have to listen to it night after night after night—these little babies being made, contemplating the disruption they potentially present to your life, especially your life at the center. It is an image of the fullness of the other: all those babies, all that pleasure, the omnipotence and violence of it.

Life in the primal scene is a permanent emergency, a panopticon—seeing all, hearing all of it, having it invade you, seduce you, hold you riveted to this all-ness, all at once. Seeing and hearing have this quality of all-at-once unlike speaking or reading, which has to be parsed out—you have to keep listening to me to figure out what I’m saying or not, have to read these words as they form a sentence that completes itself in order to find its meaning. The image I present to you, the sound of my voice, is something else. It’s something that invades you.

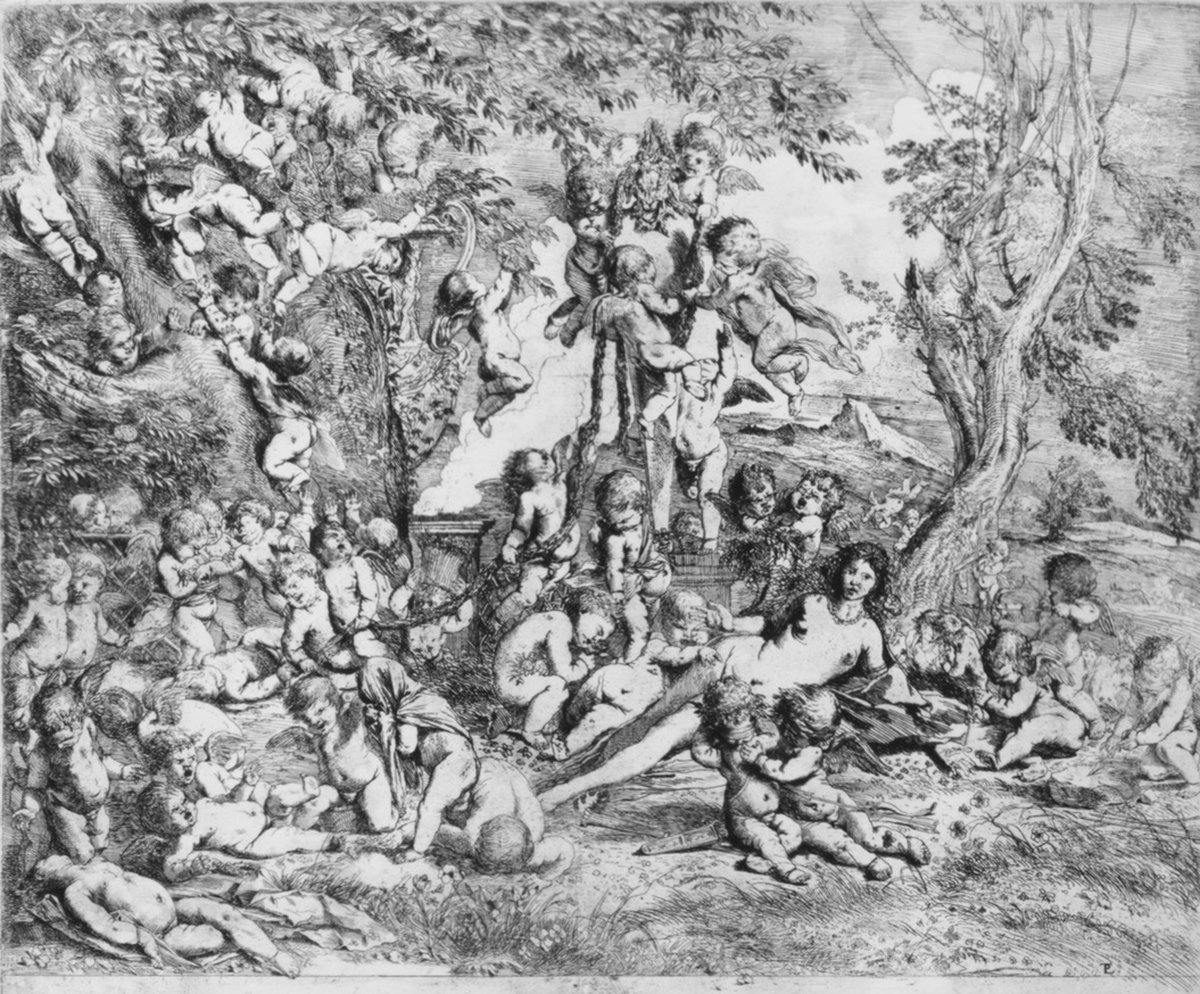

Don’t you think that this is what is happening on social media? Panic at the phantasmagoria of everyone in permanent procreation and production? This incredible 17th-century etching by Piero Testa, titled The Garden of Venus who reclines in the centre before a term of Pan and surrounded by cupids, could be an image of our mental life post-Instagram. Venus looks like she’s lounging in her garden surrounded by visions of little angels, but they are really horrible little creatures, grabbing at each other, fondling one another, stabbing her, in their excess of enjoyment. The goddess of love appears helpless, nearly in a panic, reclining in her army of children with the god of war. Love conquers all, as they say.

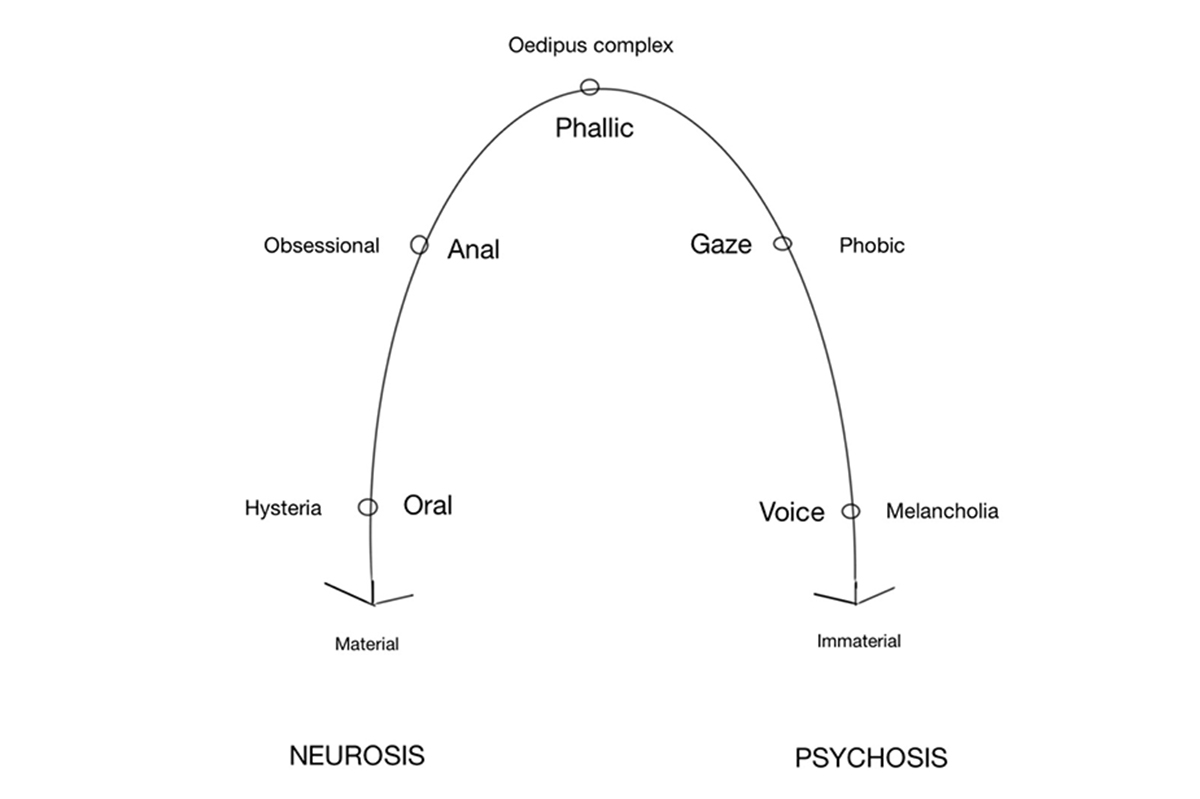

Psychoanalysis has various ways in which it describes the failure of love, sometimes categorizing these into various psychopathologies, panic just being one among a number of configurations. In the little diagnostic chart alongside this text, you can see the sexual object as tied to the various erogenous zones of the body, and its association with corresponding diagnostic categories. The oral and anal object are tied to the classical neurotic gendered psychopathologies of hysteria and the obsessional. The hysteric is the woman who believes she loves best and that loving best come in the form of a righteous demand for novelty while the obsessional wants to love no-one, wants to be self-sufficient, to have nothing demanded of him, to rest complacent in a feeling of security. They tie themselves to these oral and anal objects that they reproduce, sometimes with one another.

The gaze and voice are on the other side of the rainbow with panic (or phobia) and melancholia. They are the more immaterial objects of the body and fall to the side of psychosis precisely because one is making something immaterial materialize, hallucinating it into a reality. When we are panicked, we are being watched—the omnipresence of the gaze is there and felt. We look, but we feel seen. Melancholia is the terror of the experience of a voice that tells you what you are, that tells you how worthless you are. We scream in rage or despair because the voice in our head screams at us.

One might say that these psychopathologies have given up on love, or rather see it for what they think it is—people tearing at each-other’s bodies. Are we not caught somewhere over on this side of the rainbow? In the nest of babies, caught in states of psychotic panic or melancholia, riveted to an idea of the violence between the sexes, no less civilization as a whole? Is this not what trigger warnings are about—what we can’t bear to see or hear? Is sex-panic not the reality of all panic, panic as making itself the witness to the excessive violence and enjoyment of others without mitigation?

For better and for worse, language given over to this immateriality, unmoored from objects and reality, is close to what some call our “post-truth” world. And even if this post-truth world means existing in a state of deep panic—sometimes delusion—this would also be a world more delirious, poetic, and comical. I do believe this. I’m a structuralist Lacanian. The drift of panic and anxiety puts us into the drift of language, which is always where poetry and humor find their home, or rather, their homelessness.

It may be the one shred of hope that I have—prose and humor—which I see everywhere around me, beyond primal scene fanaticism and its panicked adherents. I do think communities are forming on these fault lines, in the contagion of panic, even as they may seek to escape it. Either way, some truth about the real state of affairs is becoming clear and Freud always wondered if we had to become this sick to get close to a truth of this kind.

Pan is said to be the first and only god who dies from the Greek-Roman Pantheon. Some speculate that this is why Pan is probably the model for Satan (who happens to look like a goat). One might wonder about this encounter with wild sexuality and panic, followed by the death of god, occurring, or so it is said by Plutarch, in order to announce the transition from the ancient to the Christian world. Great Pan is dead! So panic isn’t just about perpetual sex you imagine others are having, nor is it solely about psychotic objects, it is also these as pointing to your death.

The primal scene, no less the gaze and voice of others, is what eclipses you; fantasy is always a last stop before the reality of mortality, utter helplessness, the fact that no one has what they need really, and no one can help you with the reality of death. When you are dead you will not know you are dead, you may only know that you are dying. The only omnipotent figure then is death itself—not he, or she, or Anna Wintour, or the un-dead army, or anyone else on Instagram—which, because we have an unconscious that doesn’t know death, is never dead enough.

The best dream for last: At the end of some long anxiety dream, WWIII, the kind that goes on and on and on and there isn’t even seemingly anything to say except that one is exhausted after this kind of dream, I’m with the blind psychoanalyst I worked for while I was in graduate school. It was always amusing to people that I had this blind father figure I was leading around. I thought of him as my Tiresias. In the dream, I see him so clearly, and I say to him, “I’m sorry I don’t see you regularly.” Norbert replies to me, “that’s okay, I don’t have much of a sense of time.” In the dream I thought this was a statement about his being blind. When I woke up, I realized it was about the fact that he’s dead.

This essay was originally presented at The Drawing Center as part of the series Bellwethers: The Culture of Controversy, a series of talks co-curated by Alison Gingeras and the editors of Affidavit, Kaitlin Phillips and Hunter Braithwaite.