Reality Is Upsetting: Virginie Despentes in Conversation

Ruby Brunton

December 17, 2019

.jpg)

I first encountered Virginie Despentes long before I was old enough to appreciate her work. Growing up in small-city New Zealand, one of the highlights of the year was the International Film Festival. The year Despentes’ now cult classic Baise Moi played, a picture of the elegant lingerie-clad woman pointing a gun at the camera shone from the program’s pages. That said, I was too young to attend.

Years later, wary of a feminist rhetoric that seemed to spring from victimhood, the traditional view of gendered sexuality that rape, sexual violence, assault, became things that defined you, or even ruined you, I came across Despentes’ again, specifically her theoretical text King King Theory. She offered an alternative path to coming to terms with it all, suggesting that you could take back your power. She also seemed to be offering an expanded vision of who could be included in the feminist project. “I am writing as an ugly one for the ugly ones: the old hags, the dykes, the frigid, the unfucked, the unfuckables, the neurotics, the psychos, for all those girls who don’t get a look in the universal market of the consumable chick.” Her unapologetic language and unflinching portrayal of contemporary heterosexuality and gender dynamics have drawn her a following and heavy criticism in equal measure.

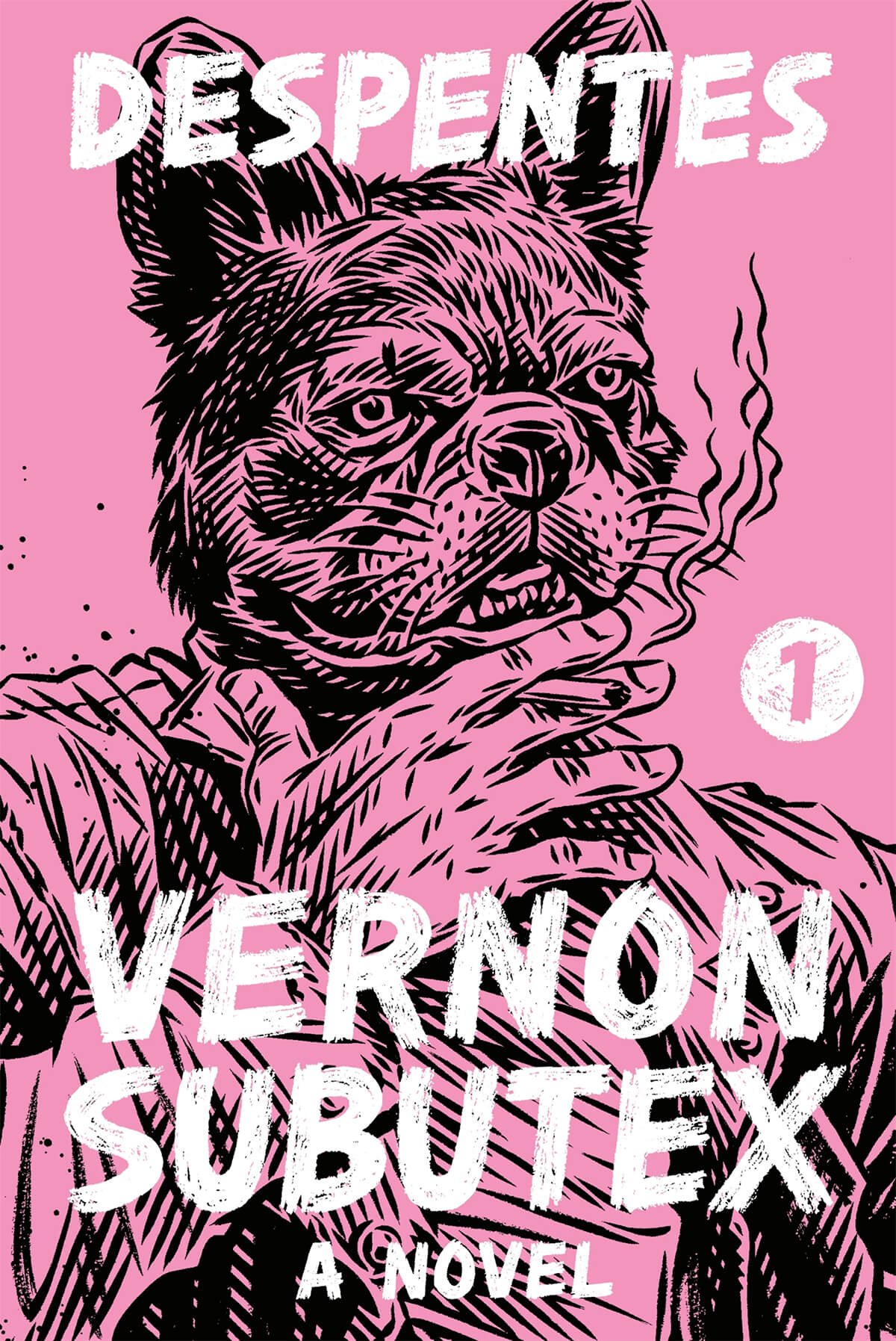

Despentes’ literary career spans decades. She wrote her first novel, Baise Moi, which was adapted into the film, in a couple of weeks. She was 23 and high on cocaine. Twenty-five years later, with an impressive literary trajectory behind her, the cocaine and reactionary anger may be gone, but the same fervor to probe the injustices of contemporary power imbalances and the pursuit of the truth remains. Her latest literary offering, the Vernon Subutex trilogy, introduced her to a new generation of readers. It was made into a television series starring French heartthrob Romain Duris, and has also recently been adapted for the German stage. Despentes doesn’t seem particularly interested in this return of celebrity. Instead, she prefers to focus on the social conditions that contextualize her writing, why she feels her generation of feminists failed today’s young women, and why it’s vitally necessary for her to stay brutally honest. - RB

Your first novel, Baise Moi is the story of two young women who go on a sex-and-murder spree after one is gang-raped. You directed the film version in 2000, and both the novel and film reached a cult status while also receiving heavy backlash in some countries. How did you feel about the book’s reception at the time?

The novel was not censored. It did not exactly meet the expectations of traditional French literature and therefore was sometimes heavily criticized, but it was not censored. I felt great at that time about the book’s reception. I was 25 years old when it was published and the book immediately reached an audience who took it for what it was—hard-boiled punk literature. I became a writer with that book and was not bothered by harsh critics. I understood they were what truly validated the novel. I was surprised by how the old French bourgeoisie felt entitled to give their opinion on things clearly outside of their cultural knowledge. It came as a surprise when old French men would draw the line between what subjects a young woman should bring to the public debate, and what tone she should use.

Why was it important to you to depict such a graphic story?

I wrote the novel shortly after discovering Kathy Acker’s short stories. I was thrilled by the crudeness of her writing. At the time I was 23, busy trying to have sex with as many hot guys as I could—and I was pretty pragmatic about where “hotness” began, so the field of possibilities was tremendous. Most of the conversations I had with the guys I was hanging out with turned around sexuality. I was also earning money when needed with sex work. So at the end of the day, sex was a very important part of my life. I wrote a novel with characters very motivated to get laid. Why not be graphic? What is so upsetting about sexuality that it should never enter direct representation?

When I wrote it I had read so many novels that revolved around male sexuality and were considered classics. I did not realize that as a girl I was not supposed to do the same, that I was supposed to bury any sexual activity under shame. But why? Sex was free, sex was unpoliced, sex was cool, sex was intense… Why should I talk about something else? I still don’t get it, especially if you happen to be a heterosexual woman, sex might be the only good thing men bring into your life. Beyond sex they are perfectly useless for any woman. So why not concentrate on the positive?

Do you think audiences are more or less open to such content nowadays?

Things have changed dramatically since 2000. What we understand as art has changed a lot. Now the only pertinent question about a movie a book a TV series or a piece of art is “how much?” To earn the most money possible you have to avoid any kind of controversy. Art is starting to confound itself with the advertisement industry: simple messages that do not bring discomfort, that do not change your frame of mind, that do not imply any risk. I don’t see how a movie like Baise Moi could be produced today.

With sex, it is far worse than it was 20 years ago. Through school harassment, bullying and revenge porn, social media has reinforced the idea of the female sexuality as deeply shameful. And my generation, the adults witnessing this catastrophe, we’ve done nothing to help young girls, to try to teach them how to be proud to be sluts, to be proud of swallowing dicks and proud of their nudity. We’ve let these young girls become targets. If a video was published of a girl engaged in sexual action it was a scandal for her. Never for the boy.

Even worse, Facebook has taught girls and boys that it is perfectly okay to be hateful, to be racist, to be intolerant, to harass, to be homophobic, to be antisemitic, to hate women—all speech is okay on Facebook. But no tits. Hate speech is ok. Your tits are dangerous, because they are sexual. We adults who know better have done nothing to protect the young girls and to educate young boys. I would say we are far more sex-phobic than we were 20 years ago. Women have still not entered sexual liberation. It was a party that took place upon our bodies, a party to which we were never invited. I suggest we crash this party, the sooner the better.

You wrote Baise Moi in some unimaginable space of time, several weeks, while on cocaine. How do you think these writing conditions affected the novel? And how have your personal writing conditions changed?

I wrote the first draft in three weeks at my parent’s house while they were on vacation. I wasn’t doing much cocaine when I was 23, and certainly did not need it to write at that time. As I was totally unaware of what kind of impact this novel would have on my life, I did not experience any kind of fear. This feeling changed a lot once I was published.

After a whole year of writer’s block, I used cocaine to write my third novel, Pretty Things. It didn’t work anymore—though I tried many times. Cocaine is not a friendly drug. It helps you a little at the beginning, then it only brings you problems. After the movie Baise Moi, I quit alcohol and hard drugs. I became a weed smoker as I did not succeed in becoming completely abstinent. When I wrote my fourth novel, Teen Spirit, I just confronted the writer’s block. I quit weed when I’m writing, which I do in blocks of two or three weeks. I’m a very anxious person and a nightmare of a writer, but it doesn’t give me panic attacks anymore. I just sit and wait. It gets so boring that I usually end up writing something.

Your next work that received international attention was King Kong Theory (2006), a personal investigation of the themes in Baise Moi, and a challenge to traditional feminism for the women that it had ignored. What do you think has shifted in contemporary feminist discourse since the book’s release?

I was bringing myself into the spotlight. I was bringing girls who want sex but are not very seductive, I was bringing fat girls, angry girls, sex workers, raped girls, proletarian girls, I was bringing everything I was into the spotlight. And I was willing to write about a pro-sex feminism that was American, that was not widely spread in France, a feminism brought by Annie Sprinkle, Lydia Lunch or Candida Royale, and many others in the ‘80s and the ‘90s. It was a statement. I am feminist, but I identify with a feminism that wants more porn, that wants rights for sex workers, that wants to talk about rape beyond those of rich heterosexual white woman.

That is exactly the discussion I was looking for when I first read King Kong Theory. We had a really conservative feminist curriculum at university. It was almost puritanical. I also appreciate that in your novels the protagonists are often just girls like me. They’re not middle class, they didn’t go on family vacations. Your latest literary project though, the Vernon Subutex trilogy, breaks with most of your other books in that it focuses on a male protagonist—the titular Vernon. What made you decide to write from a male’s perspective?

I did it before in Teen Spirit (2002). It was fun and interesting to work with a male character. I would maybe experience a feeling of uncertainty if I had to write a novel from the point of view of a spider, as I don’t have a clear idea of what is in a spider’s mind. But I have always had to listen to men talk about themselves, so I kind of felt I had some clues as to their inner monologues. We are not very different.

What’s different, in my opinion, is the public reception. I am used to working with female characters. Readers, no matter their gender, tend to be very judgmental towards female characters. On the other hand, a male character is cherished from the first paragraph. No one has ever judged Vernon Subutex for his sexuality, for example. If he had been a woman, having sex with anyone who offers him a couch, he would be severely judged. But he is a guy. He is entitled to do whatever he wants. And once you have a male character, your novel is seen as a portrayal of a generation. It becomes political. If Vernon Subutex had been a woman, the novel would not have been described as a portrait of a generation, it would have been “The sad case of a female loser who did not get properly married and was not able to give birth.” So I now intend to work with male characters on a regular basis.

Through the shifting interior monologues of the various characters we have an insight into the uglier side of human behavior and thought—a radical honesty, perhaps. Some readers have criticized the characters as racist, sexist, and homophobic. Others equate these views with the writer of the book and not the characters. Why is this radical honesty so important to you and what do you think it can tell us even when it’s upsetting?

Reality is upsetting. For example, American politics is fucking upsetting. For some of us, a way to deal with an upsetting reality is to try to understand how we got in this situation. For others, it’s to bring as much light as you can to what’s going on. If you are French and you were educated with the idea that Nazism is bad, that killing millions of people is bad, that torture is bad, that slaughtering children is bad, then you might want to understand how the extreme right can become second party in your own country.

We know who we are voting for, there is no innocence in that decision. So it’s important to ask how it happened. How can I myself know some of the privileged white people who feel the need to make their racist views public? You might also want to examine your mind because extreme right propaganda has spread on a worldwide level and there is not propaganda that does not reach you. It is not a bad idea to confront your own thoughts. If you refuse to confront the problem, there is little hope that you will be able to contribute to the solution. We are all part of the problem.

The trilogy presents a fairly bleak vision of aging. As the characters get older they become more miserable. Do you think this speaks to a particular demographic, or is it true in general?

I turned 50 this summer and I don’t think the main message has changed a lot. You turn 50 and you suddenly understand you’re going to die. Nothing in our culture prepares us for this news. At the same time, you understand what aging means. You are becoming a stranger in your own neighborhood. Things change without you, there is a strong sense of decay.

In France, what’s new for my generation is when you lose your job at 50, the job market does not want you anymore. You are not dead, yet, but you’re useless. Your future had already happened, it is behind you. I don’t remember many people from my parents’ generation who worked all their lives and found themselves unemployed after turning 50. Women suffer twice as hard here. In France it’s highly common, even acceptable, to loathe mature women. You certainly don’t want to hire them.

Recently in the Guardian you said, “I have changed a lot as a person, the anger and anxiety isn’t the same.” In which ways have anxiety and anger changed for you over time? And for your characters?

You can write a book like Baise Moi when you are 23, but if you are in the same state of boiling rage 30 years later, you are already dead. There is a level of anger which is cool in your youth, but it burns you out if you keep on working on the same energy. So I intentionally tried to tone it down.

I can’t imagine having more luck in my life than I’ve had these last 20 years. I’ve been lucky as hell. So I started to realize that maybe life was sending me a message: “Could you please try to be less radically negative about everything?” It’s hard to change your thoughts, but I suppose I’ve partially succeeded. I’m still unusually angry and sensitive, but I’m getting more stable with age. I suppose it is also chemical. With age some of your hormones weaken and leave you a little tranquility. Also, I quit alcohol for 17 years. I suppose that made me a little calmer. But let’s be sincere, nothing eases rage more than a large amount of money. There are so many anxieties that money can cure.