My Lo-Fi Wedding

Haley Mlotek

April 9, 2019

In 1970, the filmmaker Arthur Ginsberg had one of the first Sony Portapaks in the United States: a one-person battery-operated and self-contained videotape recording system. He wanted to use it for a behind-the-scenes documentary about the making of a pornographic film. Carel Rowe and Ferd Eggan were amateur filmmakers looking to film their wedding night and sell it to repay some debts. Ginsberg agreed. Five years later, the three of them ended up with something else entirely: 30 hours of sporadically filmed footage, an excruciating document of their brief engagement, staged—but legally binding—wedding, short marriage, and eventual breakup.

Self-described as “two freaky people going straight,” their decision to marry is a mystery. “Why go all the way?” Ginsberg asks them at one point. A gimmick needn’t be real for TV. Rather than answer, they monologue. They want what they want because they want it, and they find many different ways to say that. A predecessor to reality television, it’s an exercise in endurance. How long will it take for them to stop pretending they don’t notice the camera, and instead start letting the camera takes what it needs? How long can the audience stand the repetition, the posturing, the performance, and what will be the pay off?

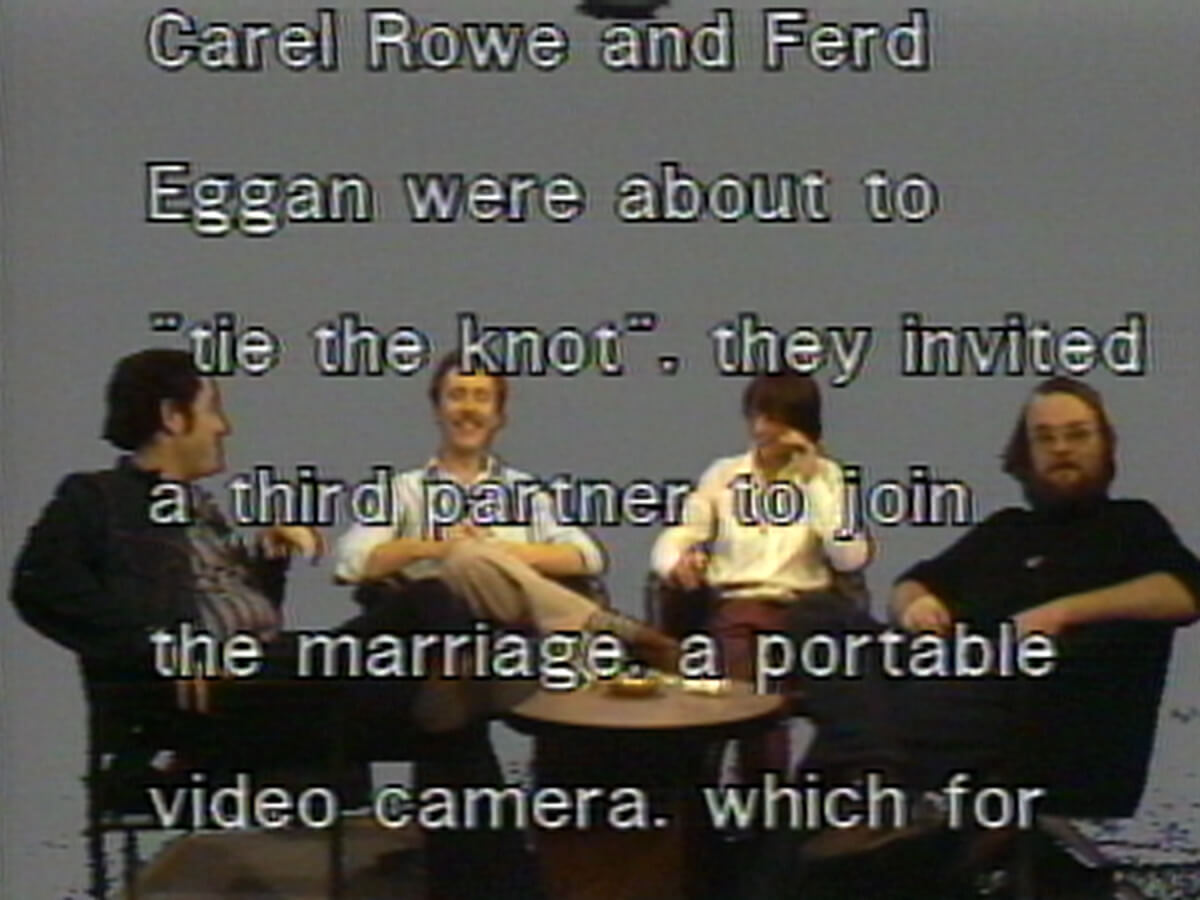

The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd was meant to be watched as a three-channel, eight-monitor video installation accompanied by a live camera feed of the audience as they watched it. Carel Rowe and Ferd Eggan were intended to be present. It was first shown in this more artistic format at The Kitchen in New York in 1971. Towards the end of this winter, in the carpeted room of Electronic Arts Intermix, a non-profit video archive based in Chelsea, I watched a one-hour version repackaged for WNET’s 1975 series Video and Television Review. The genre gets confused, as what was an art film is now lo-fi documentary remixed for a television and not a gallery audience; the film begins with the fast moving and slowly pixelating logos of public access television networks. The credits end to reveal Ginsberg, sitting with Carel, Ferd, and the show’s host, discussing the footage in the round. They are smoking, legs crossed as they recline low in their seats. They all have that VHS aura: a halo radiating against the blue backdrop of the studio. It feels like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? meets Terrace House.

The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd is a collection of scenes edited lightly, or not at all. Conversations circle without conclusion. At certain points, the scenes will cut back to the studio interview where, five years removed from what we just watched, Carel and Ferd comment with updates or epiphanies. There are, occasionally, descriptive texts printed on the bottom of the screen, like LATER THAT DAY and THE WEDDING and EVANSTON ILLINOIS 1971. They admit to self-editing—of making some decisions as to how they would appear on tape, presenting aspects of themselves they thought would be more acceptable or entertaining.

As the movie played I tried taking notes, but they were talking too fast, saying too many things. Later, I read my handwriting slanting downwards diagonally across my yellow pad: “I don’t give a shit what the public wants to see,” I’ve quoted someone as saying, but not who said it. I’m trying too hard to pay attention to everything, looking for what matters most—Carel’s center-parted hair, her long ponytail. She wears a turtleneck with a knotted scarf in one scene, a long chain necklace with a heavy pendant. “Stop directing me!” She says. “This is real life.” In the background plays the Rolling Stones song “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.”

I saw her today at the reception

A glass of wine in her hand

I knew she would meet her connection

At her feet was her footloose man

Carel speaks in song lyrics: laconic metaphors, crisp signifiers. Every sentence sounds like she should be winking at the end of it, which she sometimes does. This is because she was, in her first marriage, catapulted into being a songwriter. About ten years before shooting The Continuing Story, she was a cheerleader at the University of Arizona, Tucson, enough in love with a folk singer named Travis Edmonson to follow him to San Francisco, though not in enough of a relationship with him to have his phone number when she arrived.

Carel hunted down the manager of the Kingston Trio, Frank Werber, thinking that maybe he would know how to contact Edmonson. Instead, Weber sent her three dozen roses and by the end of her summer vacation had asked her parents for her hand in marriage. Carel described it as going from a cheerleader to trophy wife. On their first date, Werber introduced her to the jazz musician Vince Guaraldi, who played her the instrumental classic “Cast Your Fate to the Wind.” “It was like a scene in Casablanca,” Carel reminisced in a 2012 radio interview. “Frank sauntered into the club, introduced me to Vince, and said, ‘Okay, Vince, play it for her.’” Vince told Carel he wanted lyrics, which she wrote driving back and forth over the Golden Gate Bridge and thinking about Travis Edmonson. The lyrics to the last verse of “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” are:

So now you’re old, you’re wise, you’re smart

You’re just a man with half a heart

You wonder how it might have been

Had you not cast your fate to the wind

With the royalties from that song Carel refashioned herself into filmmaker. When she introduces herself to Ginsberg’s camera, she says she makes documentaries and shorts, describing them as “beautiful films.” She taught film school for two years, did commercials, but couldn’t get work. “Being a girl, I couldn’t get into the American Film Institute…because every time I get a job as a camerawoman I was taking away someone else’s job. They had families, I was a career woman.” When she finishes that story she winks.

Before beginning production on The Marriage of Carel and Ferd, Carel had worked on about twenty fuck films, as she calls them, estimating that she had acted in about thirteen and done editing, sound, or directing for the other. “Making fuck films ruined my life completely,” Carel says. “It’s not as though if I made food commercials that I wouldn’t eat. But fucking is all in your head, and when they turn the lights on and it’s not in your head, you just have to reach back in there and commit the sin of fantasy.” She thinks for a moment. “I wish I could think of a metaphor but I’m dropping off again.” She speaks very cooly, like someone who knows how to get the attention of a professor.

Ferd was, at the time of the filming, an openly gay man struggling with a heroin addiction. When they describe their post-marital plans, Ferd talks in junkie logic. He is kicking dope, of course, and he’ll do it by going back to live with his parents for a month. There’s no dope there, he explains, and he wouldn’t take any with him because he couldn’t afford it even if he wanted to, not that he does.

The details of how they met are glossed over, which adds to the feeling of starting a story in the middle. She made a film with Ferd, part of their ongoing attempt to write pornography as a coherent narrative. As Ferd describes it, not only was the film “hated by everyone who saw it, audiences left notes saying it was ugly and had nothing to do with love.” It was an S&M movie; Ferd somewhat pointedly says they made it because Carel was “under the impression she was into” it. Carel does not dispute this. “Yeah,” she responds, no longer rating fantasy as a sin, “movies are real therapeutic, you can just act out your fantasies in a script.” She does take offense to his description of it being a horrible movie, saying if they were in sync it would have been a good movie. “We’re hardly professional,” she quips to the camera, the wink back in her voice. “But we mean well.”

At the time, Ferd was dating Gary Indiana, who appears only once, but his status as Ferd’s lover results in one of the film’s true fight scenes. If Ferd really does get married and return to Illinois, Gary says to Ferd but for the camera, he’ll take strychnine and then lie in a coffin like Sandra Bernard with a dozen American beauty roses draped across his chest.

In 1999, Indiana wrote a profile on Ferd for POZ magazine. We should all be so lucky to have our former lovers describe us the way Indiana does. Physically, he says Ferd was “a rakish Nordic sybarite: a queerly angled face with concupiscence (a word he’d definitely use) written all over it, a suggestion of the world-weary anguish in his hooded eyes.” Emotionally, Indiana says that “[I]n the netherworld we lived in then, Ferd was a thinking person’s love god, surrounded by many boyfriends and a female fiancée, a dandy whose air of languid, charismatic decadence spoke to a general disenchantment, after Manson and Altamont, with the concept of ‘good vibrations.’”

Ginsberg is less lucky to have Indiana’s attention. He describes what Ginsberg optimistically referred to as an “extended narrative” as “a vague project that soon became an endless documentary.” While that endless documentary was evolving, Indiana explains, he flew home to Boston and had “a nice long nervous breakdown, the onset of which you can see in the video.” In his one on-camera scene he takes Carel’s cigarette and uses it to light his own, the uneasy affinity that naturally occurs between two people fucking the same man. It reminds me how much I miss smoking, which is to say, it reminds me how much I miss having an excuse to share something that feels good enough to ignore how bad it is for both of us.

Other characters include Richard, who Ferd calls an “old friend” of Carel’s in a tone of voice that makes it clear what kind of relationship it actually is. Carel describes him as a “wealthy older man” draping the word wealthy the way Richard wears his scarf. Richard, credited without a last name but later referred to as a Paramount executive in Indiana’s memoirs, does not like this marriage; Richard does not like this film. Richard likes Carel and Carel’s films, but he does not understand, and he does not approve of whatever this is.“It’s going to be a huge downer for everyone watching. To watch someone getting married? Marriage is a wet blanket on a relationship. I mean…marriage doesn’t last in America! It just doesn’t last!” He does not get why, if they want to make a movie about the consummation of a wedding night, they actually have to consummate a wedding. “Make the commitment! Just don’t sign any papers!”

“Marriage can transcend the legality,” Ferd retorts. “We want to go through the hassle. We want to tie the knot.” Richard remains unconvinced. Richard knows they want to tangle the knot.

Before the wedding Carel and Ferd have a fight about Indiana. “Gary was lying in my lap, and I was holding him, and Carel got real pissed off,” is how Ferd describes the night before. Carel says Ferd is always languishing with other men—her enunciation carries the meaning she’s not yet willing to put into words. Ferd’s response is: what other men have I ever languished with? During this fight Ferd posits that she might be nervous, and she might be trying to say theatrical things for the camera. “I don’t want to gain new lovers!” Carel says. “I don’t want a continual stream of excess people interfering and directing and meddling with and…acting as catalysts. I don’t want all those outside forces of lovers, those intense little lover things, all these other people.”

On their wedding day, someone remarks that for the first time they seem speechless. “We’re struck dumb with terror and awe,” says Ferd. He got a haircut and is wearing a suit. Carel wears a turban and big earrings. They’re both beautiful. Guests are taking photos of the camera instead of the couple. The wedding vows are:

You are here to enter the unit of marriage. You are here to present a media show. We, your friends, are the media of that media, as it is the media of us. The rings you are about to exchange will bind your marriage by sight, the media will bind it by the minds, and you will soon consummate it in action. That this marriage will not be complete until its separation from the media disappears. To this present media show, you Ferd, and you Carel, and we your friends, are the actors in that media show. You are here to enter into the unity of marriage. That unity will be found only when you and therefore we lose our identity as actors and become solely the media. For in truth, we are both the media and the message.” There are Hebrew blessings for the wine, and Ferd stamps the glass. “And by the virtue of my position as the pronouncer, I now pronounce you man and wife.”

In the scene where they attempt to consummate the marriage, they move slowly and with far less energy than they had for each other in earlier scenes. (They admit later this did not technically happen on tape; we see the beginning, but no finale.) “That was the first time I had the feeling that the video thing—not the movie so much—but the fact of the video was there, and all these other people were standing around watching…it was for everybody else,” Ferd reflects. “We hadn’t gotten married. The television audience had just had a marriage.” Carel calls it an orgy marriage. Ferd continues that he felt like they were the only people involved in the production who thought it was real. “It was encrusted with all this media hardware, but it was still a real experience. We were really getting married.” I believe him. Performance is not without sincerity.

Later, Ferd will say in the studio that he cannot figure out what this documentary is, saying it is “obviously not entertainment. It’s not soap opera. It’s too real.” “Oh, I disagree,” says Carel. “I think it’s titillation and entertainment from a soap opera point of view. That’s the sick love story of it, that’s what they get out of it.” Like most arguments between formerly married people, they’re both right, but I would never tell them that. (“This is a McLuhan nightmare,” Carel comments later from the studio set.)

The second half of the film is too lonely to look at, too intimate to look away. I would have watched all thirty hours if they had been available and also I hoped it would end every minute it played. Like a marriage, the film is the story of two people who have what they are not even sure they want. Like a marriage, the film only feels like it could last forever. Carel and Ferd have moved to Illinois, where she gets a job at a bakery for $1.59 an hour, and Ferd reports that he is sober. This is when Ferd and Carel were left alone with the camera. Apparently Ginsberg could no longer be in the room with them. The feeling was mutual. In one scene Carel calls Ginsberg “awful Arthur” when she sees him after a few months apart, laughing as she says she’s trying to get away from “the video vampires.” Instead they interview each other:

Ferd: Do you think that any of it is acting deliberately childish in order to be treated like a child, to be taken care of the way a child would be taken care of?

Carel: Maybe, yeah.

Ferd: Do you think that you’re protecting yourself by having a career?

Carel: In a way.

Ferd: Do you think your fears about my homosexuality are objective or are they used as protection?

Carel: All that has become part of the tapestry. The homosexuality is just used as a weapon. I mean, I don’t think you’re gay.

Ferd: Well, I can assure you I am.

*

In 1973, An American Family premiered on PBS. Edited into twelve episodes from three hundred hours of footage shot over seven months, the original airing had a weekly average of ten million viewers and is considered the first true reality television show. Margaret Mead said An American Family was “as new and significant as the invention of drama or the novel,” while Jean Baudrillard said the show was a sign of “dissolution of TV in life, dissolution of life in TV.” It was supposed to be a documentary about the Louds (I swear that is their real name), an average upper middle class family living in California.

Coincidentally or not—there is some question as to whether or not the producers manipulated the family for more drama—it ended up being a document of the parents’ separation and eventual divorce. Since then, the providence of reality television has stayed similar, angling to get behind closed doors. This is, I think, a response to the increasingly hermetic nature of the domestic unit. As families became smaller and more self-contained—less a part of their community—what happened in these tiny enclaves became a matter of intense interest, the impolite questions the ones we most need answers to. The illicit imaginings of what a neighbor might be doing or saying, paired with the accountability a camera provides, makes the boredom of reality worth it.

Ferd and Carel’s film, released two years later, does not exactly fit into the historical arc of reality programming, but it shares the same moods—the desire to be watched taking shape around the shame of vanity, of need. Ferd and Carel call this the “Carson Complex,” the idea that somewhere inside of everyone is the sense that they should be thinking of their life as the stoically comedic anecdote they’ll share when a late-night host inevitably calls for an interview. Carel says she doesn’t consider it a complex because Johnny Carson is “fantastic.” Instead, it’s the pressure to be really good on tape—“self-effacing,” Carel clarifies. “The camera gives you a choice of realities, doesn’t it?” Ginsberg says from the studio. “Either you mean it or you don’t really mean it, then you can decide afterwards.”

“I think we’re really good on tape,” Ferd admits. “I think the thing that makes us good on tape is the times when the performance [does] the least, the times when the conversations are…the most banal. As weird as it may seem, considering that I’m a homosexual junkie, it seems to me that we read as very ordinary people.”

“We’re far less amusing because we’re simply freaks,” Carel says. “Mundane freaks. Arrogant, hostile, radical, disappointed, lonely, everything that everyone else is.”

Ferd and Carel both had their own celebrity ambitions, and they share that they used to debate if it would be better to be rich or famous. Ferd says he married Carel thinking that they were all [in an] “Andy Warhol movie—closer to Trash then Empire. It turns out you can’t be in a movie all the time.” “Now,” Carel says, “all I want is to be employed.” Ferd echoes her. “Given that it’s 1975 and the country is falling apart, I just want to be employed.” The interviewer says so much for the sixties.

Richard—wealthy Richard—did end up helping Carel, in his own way. He supported her PhD at Northwestern, and at the time of the WNET taping she says she is a full-time faculty member of San Francisco State University, teaching film theory, history, and criticism. Ferd, meanwhile, went back to school to get his BA and MA in history, and became a teacher for elementary and high school students. Ferd would later become a celebrated activist in Los Angeles and Chicago—Indiana described him as “L.A.’s top AIDS policy maker.”

He died in 2007, his obituary describing him as “a veteran of the ‘new left.’” Ferd hosted the launch meeting for DAGMAR (Dykes and Gay Men Against Racism/Repression/the Right Wing/Reagan) which was the first activist group structured around HIV/AIDS advocacy in Chicago, and the demonstrations they participated in contributed to, among other successes, the opening of the AIDS ward at Cook County Hospital. From 1993 to 2001 he was the AIDS Coordinator for the City of Los Angeles, and fought for safe housing, needle exchanges, and self-organized programs for women living with AIDS. In his obituary, he is credited as the co-writer and co-producer of The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd; it is also noted that from 2003 to 2005 he wrote what he called a serial “e-novel” called The Continuing Story…on his website.

I returned to Indiana and his love letters as I was writing this. Ferd appears as a central character in Indiana’s 2015 memoir I Can Give You Anything But Love. He told The White Review that he had known it was an important friendship for him, but that writing it released him from “certain myths” he had told himself about their relationship—primarily that Ferd always felt that he was doing what he should be doing, and Indiana always felt like that was true of Ferd, not at all true about himself. Ferd was a writer and artist who wanted more time to do that work; Indiana admits to a feeling of guilt for not becoming more politically active. He says he can’t imagine that Ferd’s other friends would find his portrait of him at all adequate, but then, most of us prefer our own lenses for the people we love. He writes more of the triangle that existed between himself, Ferd, and Carel (their shared cigarette), saying he thought of himself as a “wayward urchin they’d irresponsibly adopted,” part of their collection of people. He reminisced about the pull he felt towards Carel, as well as Ferd, how seductive and spellbinding she was: She had the “vibe of somebody who’d lived the nightmare in a big, expensive way…she seemed implacable enough to launch a military coup in South America.”

Watching The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd, I saw their cruelty towards each other, reading it as Carel being unwilling to accept Ferd for who he was, Ferd resentful that Carel made him responsible for the conditions of their marriage, though maybe I’m wrong. I could say what I thought I saw in their relationship with each other, with the filmmaker, with people like Indiana—flatter myself into thinking I am not part of the faceless audience but another apex of a triangle between them. But then I would be confusing the camera for eye contact. I will always prefer realism to reality, the distance that makes scenes into narrative and gives a story its meaning. No one knows what goes on in a marriage except the people in it, the truism goes. I have often thought that the sentence could stand to be shortened to no one knows what goes on in a marriage.