Second Skin

Philomena Epps

September 10, 2018

I tried to keep an open mind during the press preview for Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up (through November 4th) at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. But after observing the #InspiredbyFrida selfie competition, with a frozen margarita prize; after the cactus wall hangings, the bottles of hot sauce, the cans of refried beans stacked in the gift shop; not to mention the staff accessorized with floral garland headbands—I remembered a tweet that went viral during the Conservative Party Conference in October 2017. Hannah Jane Parkinson exclaimed, “Can I just point out that Theresa May is wearing a bracelet of Frida Kahlo, a member of the Communist party who LITERALLY DATED TROTSKY.”

Surely, this tweet—which has 22,489 retweets and 55,352 likes at the time of writing—was the zenith of the unbridled sanitization of Kahlo’s image. Not just a Communist, but a queer, disabled woman of color, decorating the wrist of a prime minister who has, in the words of direct action group Sisters Uncut, “subjected women and non-binary people to vicious attacks on [their] safety, liberty and welfare … consistently ignored the demands of disabled activists, communities of colour, working class and migrant campaigners … forcing through a swathe of sinister cuts, laws and public service sell-offs.”1

However, May’s cognitive dissonance seems well matched by the V&A’s sponsorship by one of the country’s dominant property developers, Grosvenor Britain & Ireland, who are “honoring” Kahlo (as not just the “original selfie queen” but “an artist of substance”) across Belgravia, one of the world’s wealthiest neighborhoods, with “a range of exclusive products and experiences” throughout “key retail destinations,” from “headdress-making sessions to self-portraiture classes.”

*

In 1999, the scholar Margaret Lindauer published Devouring Frida, tracing Kahlo’s cult status within art history and popular culture, her symbolic significance to the feminist art history of the 1970s and ‘80s as a forgotten woman artist, and the notoriety of her image in the early ‘90s due to the circulation of her self-portraits and archival photographs in fashion magazines.

She writes about how the particular emphasis on Kahlo’s aesthetic images, her “exotic” dress and so on, “consecrating the Frida Kahlo ‘look’ of passion, indulgence, and ostentatiousness … sustains the notion that dressing-up constituted Kahlo’s sense of her own identity … [and] completely obliterates any suggestion that Kahlo was a producer of socially, politically meaningful paintings.”2 I wonder what Lindauer would make of the past twenty years, of Mattel’s recalled Kahlo Barbie, or the whitewashed Snapchat filter.

Lindauer states that Kahlo’s narrative has been insidiously isolated from broader social contexts, constructed akin to fictional, patriarchal representations of sick women, and historically revolving around two aspects, steeped in misogyny: her tumultuous marriage to Diego Rivera and the interminable deterioration of her body. Often recounted as a litany of physical and psychological symptoms, she is revered for her “triumph” in creating art in spite of her suffering. Kahlo endured intense physical pain throughout her life. She contracted polio in 1913. And in 1925, was impaled by a metal handrail in a tram accident, breaking her spinal column and pelvis, and fracturing her right leg in eleven places, which was amputated in 1953 due to gangrene.

Kahlo often presented herself as a talismanic object in her paintings, a composite of fragments. This self-identification has an uncanny relationship to the way her image has been appropriated since her death—broken into parts, objectified, and packaged for commercial profit. Despite V&A curators Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa’s desire to counter this—as they write in the exhibition’s publication, to “meet, face-to-face” the “spectre of Kahlo’s essence” anew—the exhibition colludes in the reduction of her identity. It is seemingly more engaged in the apolitical, decorative sphere; Revlon lipstick kisses, or the misappropriation of the ribbon-around-a-bomb motif first postured by André Breton (which referred to the power of her painting, and had nothing to do with “dressing up”).

Garments and possessions in a museum context inevitably function as hallowed totems and relics; subjectivity frozen in objectivity. However, there is an unnecessary element of fetishism latent within the choice of display cabinets, with glass cases built into multiple facsimiles of Kahlo’s four-poster bed, complete with white sheets and pillows. Her pain becomes aestheticized, made trite.

The exhibition displays have the potential to create a narrative of multiplicity, an intersectional understanding of how her identity, nationality, disability, sexuality all coalesced. We see the uneven shoes with built-up heels to allow for the leg shortened by polio; the prosthetic leg which came later, embroidered with red and green Chinese satin and a little bell; the surgical corsets and back braces, a result of over thirty operations, all to be hidden under the traditional indigenous dress style she adopted, the long and wide skirts, shawls, and square-cut blouses that referenced the traditions of her matriarchal Tehuanan roots.

These narratives are brought to bear in the exhibition’s associated publication, but fail to land in situ. Rather, her body is split into seemingly disconnected parts to be observed, as opposed to being considered as the body whole. The singularity that the exhibition also overstates with regard to Kahlo’s style is inevitably flattened and obscured by the overpriced replica embroidered tunics, huipils, scarves, and jewelry available in the gift shop, where visitors are welcomed into a false familiarity, invited to “Make Your Self Up.”

Looking back, the viewing experience felt voyeuristic, invasive. For someone who surrounded themselves with vibrant color, the dark, spot-lit rooms were melancholy and austere, while having a mannequin faced away from visitors (towards a mirror), dressed in the clothes Kahlo died in, was overtly morbid. This also seems particularly inappropriate considering death is not a taboo in Mexico, rather embraced with fondness and jocularity, as the poet Octavio Paz wrote in his 1950 essay “The Labyrinth of Solitude,” “The Mexican … is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it; it is one of his favourite toys and his most steadfast love.” If I am to “meet, face-to-face” with Kahlo, I would rather it be her beautiful cobalt-blue house—Casa Azul—in Mexico City: her home, on her terms.

*

In 2012, the Japanese photographer Miyako Ishiuchi was invited to Casa Azul (also known as the Museo Frida Kahlo) to document Kahlo’s possessions. An exhibition was organised in 2013, and a book was published. A selection of these photographs from the resulting Frida by Ishiuchi (2012-15) series were exhibited at London’s Michael Hoppen Gallery this summer as part of Frida: A Photographic Portrait. Considering the overstated approach at the V&A, it is intriguing that it was Henestrosa who had first contacted Ishiuchi. An artist unfamiliar with Kahlo’s work, the Japanese photographer was selected on the strength of her tender, understated oeuvre, often capturing objects that bear the traces of now absent bodies.

In Mother’s (2000-2005), Ishiuchi photographed her mother’s objects after her unexpected death. In the ongoing Hiroshima series (2007-), she documents the clothing of those killed by the atomic bomb on August 6th, 1945, now preserved in the archives of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Ishiuchi’s mnemonic interests could first be gleaned through her photography in the 1990s of human scars, with the intricate textures of her subjects’ skin depicted at close range. A physical imprint of memory and trauma, a scar is also a mark of the healing process, holding the promise of repair, and the tenuous relationship between the body’s simultaneous fragility and endurance.

For Ishiuchi, clothing is a record and extension of the flesh left stranded once the body it was mapped to disappears. Writing about how an individual’s presence clings to kimonos after the original owner has died, she muses, “You can get rid of the smell by airing or washing them, but that doesn’t take care of the aura … Anything that you wrap around your body … is really a second skin … wearing a kimono that someone has worn before is like wearing someone else’s skin.”3

The Mother’s series initiated Ishiuchi’s transition from exploring the effect of time and trauma on the body—nails, skin, hair—to considering how the objects and clothes that people choose, can be read backwards—as afterimages—to address these same themes.

“We may imagine how it would feel for Ishiuchi to touch her mother’s belongings after her death, and we may experience an intimacy with this mother—we come close to her slips, her girdles, her blue eye-shadow stick with the texture of her eyelids still imprinted upon it—as close as one can come now to the touch of her skin. And many of us cannot help also remembering the girdles and old red lipsticks, the hairpieces and dentures of our own grandmothers, also lost,” the scholar Miryam Sass writes in response, “This plurality is not a levelling of differences … but the heightening of specificity until it becomes so precise and so clearly seen that it ruptures from within, paradoxically bringing us closer to the unique particularity of the objects and memories of our own lives.”4

The illusionary relationship conjured by Ishiuchi, the overwhelming specific intimacy of a stranger, is what is lost at the V&A. The Frida by Ishiuchi works are chromogenic prints, simply titled and numbered. At Michael Hoppen, they are hung at varying eye levels. Each differs in size; some are large format, others much smaller. Some are cropped to focus on specific details. Always working with a 35mm hand-held camera, Ishiuchi prefers bright light, either relying on the natural sunlight or using an artificial light-box to simulate the same effects.

This warm aesthetic brings the clothes to life, denying the ossification that might occur as a result of being kept in dark museum or dusty archive. There is a strong sense of movement, with careful arrangements, folds and creases, conveying corporeal dynamism. Skirts and blouses, with their well-preserved intricate colour, patterns, and textures, are fanned wide across the frame. A tired old green swimsuit. Black gloves with thin, elongated fingers, as if reaching out to us.

We can read Kahlo through her clothing’s indexical traces—the imprints of her body found through paint stains, cigarette burns, and customizations, such as a pair of old net tights puckered by darns—which signify as clues and allusions to what Barthes’ notes in his 1964 essay “Rhetorique de l’image,” as the having-been-there. Like shadows, the clothes represent the negative, an allusion of the positive flesh, which is now absent. They are iconic—pictorial representations of Kahlo’s body—but also indexical in that they hold the residual imprint of human presence.

Without a body to adorn, these items are preserved as artifacts, engrained in museological discourse as both historical evidence of and a substitute for her self. However, Ishiuchi’s rendering moves towards the sacred, alluding to their talismanic quality, and casting them as relics. The religious discourse surrounding relics can be aligned with the museum, as both see objects infused with sufficient value or trace of a person enough to sanctify a space. There is a sense of distance and reverence to Ishiuchi’s process, emphasizing a fleeting temporal exchange as opposed to a stopped clock; “I can’t photograph the past. I can only photograph the present … [and] the space and time I was sharing with these very particular objects.”5

*

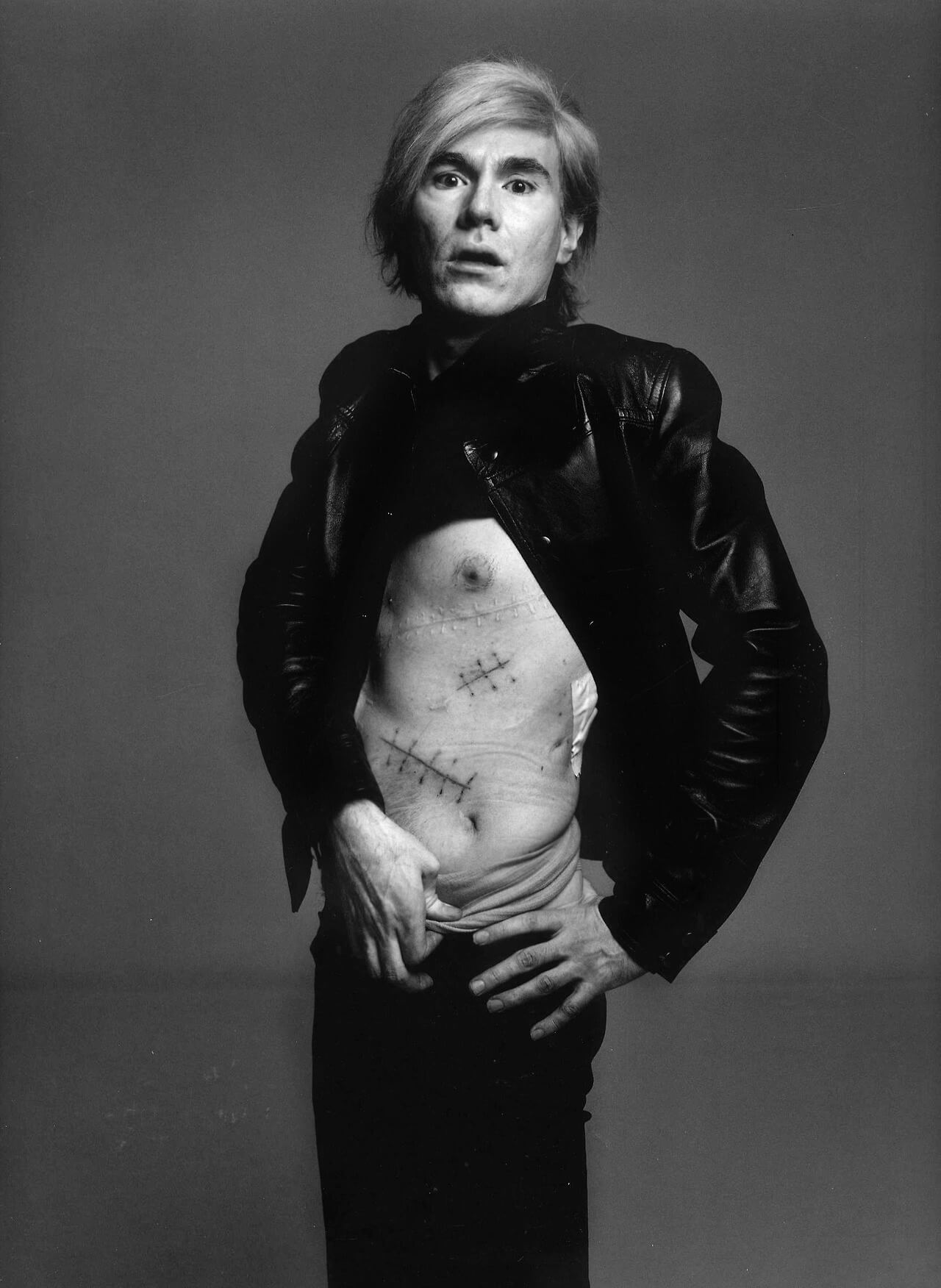

In 1968, the writer and activist Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol. He spent two months in the hospital, where intensive surgery was required to repair his damaged lungs, esophagus, spleen, liver, and stomach. He was left scarred and disfigured, required to wear a surgical corset for the rest of his life. These corsets and bandages were hand-dyed in pastel colours by his friend Brigid Berlin, in green, lavender, orange, lemon, and blue.

“It’s easy to forget that Warhol was a stitched work in his own right,” writes Olivia Laing in The Lonely City (2016), “The corsets made me more aware than anything of Warhol as a physical presence, a body that was always on the verge of falling apart. He spent so much of his life trying to stick himself together, an assemblage of purchased parts: the white and blond wigs, the big glasses, the cosmetics he used to conceal his patchy reddish skin, his ugly open pores.”6

After the shooting, and the years of covering his body prior to that, Warhol revealed his scars in Polaroids he took of himself, and in portraits by other artists. Notable examples are the black and white series by Richard Avedon in 1969, in which Warhol stands with arms outstretched, a Christian icon in black leather, and a softer, androgynous painting by Alice Neel from 1970, which Laing describes as “an image of resilience [with] a profound, unsettling vulnerability.”7

Throughout his career, driven by his own flaws and insecurities, Warhol explored the fragility of the body, often portraying images of disaster and trauma: death, illness, and surgery were consistent themes in his work. These themes are often flattened posthumously, along with the intersection between his sexuality, queerness, and the construction of his public persona. Like Kahlo, Warhol is one of the most visible artists in popular culture. Both have been ossified into hollow curios: itemized as Campbell soup cans and pink dahlia flowers, appropriated as costumes through silver wigs and sticky-tack unibrows.

“For someone so closely aligned with the tropes of beauty, Warhol noticeably cast his ‘beauties’ under a thin veil of pain, anxiety, and suffering,” writes Jessica Beck in response to Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, an exhibition she organized at the Andy Warhol Museum in 2016. “There are transformative moments, too, as with paintings in which a bodybuilder and Christ are brought together—a symbolic union of myth and flesh.”8 Along with these idealized—and often cropped—specimens of the male physique, he appropriated images from plastic surgery advertisements, along with commercial products, wigs and corsets like his own.

Warhol was clearly fascinated by the fragility of the body, and its potential to be extinguished in an instant, perhaps epitomized by his vivid and macabre silkscreens showing mangled car crashes, the mutilated flesh of accident victims, or the looming threat of the empty electric chair. He juxtaposes the memento mori motif of his 1976 Skulls series with a statement written a year later in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again: “I don’t believe in [death] because you’re not around to know that it’s happened. I can’t say anything about it because I’m not prepared for it.”

In addition to her autobiographical self-portraits, in which she responded to her childhood, marriage, abortions, and hospital trips, Kahlo also held images of horror close, through her collection of hundreds of ex-votos, which are kept at Casa Azul. These small, devotional paintings on wood or metal offer humble gratitude to the Virgin or saints following salvation from assault, loss, imprisonment, or illness. Many of Kahlo’s focus on injury or road traffic accidents. A man’s legs stuck under a car echoes her own accident.

*

In 1944, in the midst of multiple operations, Kahlo was required to wear surgical corsets to support her body. They were made from plaster or leather, topstitched and shaped over an internal steel frame, and secured with buckles, straps, and lacing. She painted over them. Akin to her illustrated journals (also begun in 1944, and filled with poems, dreams, and thoughts) they functioned as autobiography blended with artwork—an extended canvas, covered with collaged scraps of fabric, photographs, and mirrors, and drawings of animals, foliage and feathers, the sun and sky. When they took away her paints, she used lipstick and iodine instead.

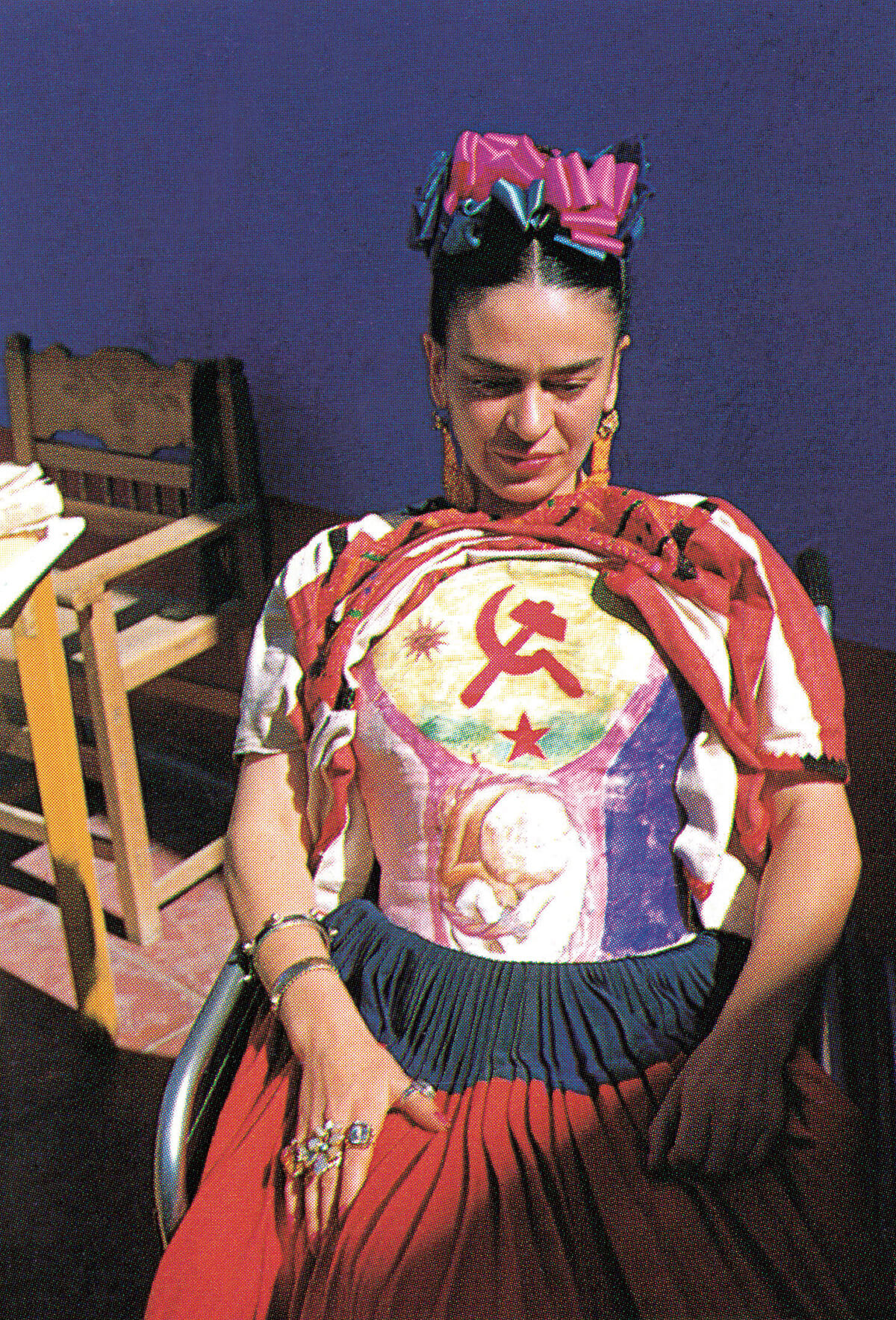

A 1951 photograph by Juan Guzmán shows Kahlo propped up in bed, painting. One hand holds the brush, the other a handheld mirror. An open circle has been carved into the plaster cast, revealing her painted pink abdomen. Rings, necklaces, and earrings decorate any exposed flesh. Made from gold, beads, jade, and shells, her jewelry often incorporated Aztec symbols and glyphs. These bits of mythology linked Kahlo to the greatness of ancient Mexico, a genealogy fusing symbols of the Aztecs to communism.

In a vibrant color photograph by Florence Arquin, also from 1951, Kahlo sits with her blouse lifted, revealing the cast decorated with a deep red hammer and sickle, and below, a tender image of a fetus. The bold proletarian symbol signifies her political fervor. Kahlo notably changed the date of her birth to July 7th, 1910: the first day of the Mexican Revolution. The way the skirt meets the corset, the stiffness of the cast in relation to the fluidity of the spread pleats, eerily foreshadows how Ishiuchi would arrange them, six decades later.

Before the tram accident, Kahlo had been taking science courses as part of her training to become a doctor. These studies, and the visual analogies and metaphors used within medical discourse, were often weaved into her paintings and can be seen throughout her diaries. “Internal organs and processes were often seen outside her body,” writes Sarah M. Lowe in her foreword to Kahlo’s diaries, published in 2006, “while she used x-ray vision to picture her broken bones and spine.”9 Using this x-ray lens, one can see how the curled body of the fetus is situated precisely where Kahlo’s womb would be, a moving reference to her infertility, and another icon of resistance against the stigma and silence that would have surrounded such issues.

After her miscarriage in 1932, Kahlo made her only lithograph, based on anatomical illustrations and botanical drawings from Aztec manuscripts. The body is split in two. One side traces the loss of her unborn child, while the other conjures her artistic rebirth, palette in hand. Akin to these self-portraits, and the allegorical symbolism in her journals, her corsets were transformed into active sites of resistance: the personal made political.

*

In 1984, in symbiosis with the feminist art revisionism that had ushered in this integration of the personal and the political, The Women’s Press published Roszika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. By reclaiming the denigrated site of needlework as a method of activism, women’s craft was promoted as both a legitimate form of discourse and a means of resistance to patriarchal domination. The current exhibition at The Palestine Museum, Labour of Love: New Approaches to Palestinian Embroidery (through January 31, 2019), explores these ideas, and the role of embroidery in Palestine—shifting from a historic practice to its contemporary significance as cultural artifact and marker of national heritage.

“Embroidery is a gendered activity, historically connected to the life-cycle of village Palestinian women,” curator Rachel Dedman writes in the catalogue, “Amid the tectonic changes and violence Palestinian society has undergone in the twentieth century, embroidery’s relationship to gender has remained absolute, though figured in different terms … [and] contributed to the construction of roles for women as labourers, as militants, as organisers.”10

Just as with Kahlo’s politicized dress—the painting of a hammer and sickle as a potent carrier of her ideological beliefs, a way to proclaim it to herself and others, the symbolic jewelry, and the singular choice of traditional Oaxacan style—Labour of Love considers how women’s bodies and the particularities of clothing work in tandem to both produce and perform a blurring between public and subjective identity. In 1987, when the occupying Israelis confiscated Palestinian flags, women began to stitch rifles, maps and political slogans on their thobes (a type of tunic).

The Intifada dresses, in particular, combined traditional motifs with explicit symbols of nationalism: the cypress tree motif is re-worked in colors of the Palestinian flag and the silhouette of Palestine is stitched onto sleeves in endless repetition. “These dresses, of gunmetal greys, blues and blacks, could not be taken from their bodies, and thus became powerful visual expressions of protest,” explains Dedman. They operate on another register, speaking an additional visual language. They become another kind of second skin.

*

In 1953, after her gangrenous leg was amputated, Kahlo captioned a painting in her diary of severed legs, with the feet arranged neatly like a Grecian statue on a plinth, with the phrase, “Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?” Branch-like sprigs sprout from the disembodied calves, her poetic, scientific symbolism, with “roots and veins, tendrils and nerves, all routes for transmitting nourishment or pain.”11 This notion of wings in lieu of feet—the imaginative and transcendent potential in Kahlo’s drawing—can be found in artists working in the margins of fashion and disability activism today.

The ongoing Crip Couture series by Sandie Yi, an artist undertaking a doctorate in Disability Studies at the University of Illinois, disrupts the boundaries between ethics and aesthetics, seeking to re-imagine conventional and standardized prosthetics as a collection of wearable works. For Yi, “the objects and their wearers call for a recognition of collective Crip experiences and suggest the possibility for a new genre of wearable art, Disability Fashion.”12

Cripness is a political position on chronic illness and disability that subscribes to The Social Model of Disability. The model was developed by disabled people in the 1970s to give them the ability to discuss their own lives through considering the ways that society has been organised to create barriers. It is opposed to the Medicalization Model, which centers on impairments and differences.

Yi, whose family members have been born with variable numbers of fingers and toes for generations, was motivated by the way able-bodied individuals sought to normalize her unconventional body. Each item—often referred to as jewelry—is designed based on an individual’s experience of the medical sphere, the nuances of their physical position, and state of mind; “Rather than rejecting the notion of physical alteration, I provide intimate and empathetic bodily adornment, not as a correctional physical aid,” she writes on her website, “but as a tool for remapping and engaging with a new physical terrain.”13

“Gloves for 2” (2005), in which Yi has cut and re-stitched a pair of orange gloves to fit a hand with two digits, brings to mind Kahlo’s customized boots with their asymmetric heels. For “Dermis Leather Footwear” (2011), latex, cork, and rubber are brought together to create a unique collection based on the specific needs of a friend. The focus on labor-intensive and traditional hand-crafted techniques in her more decorative works—crochet, sewing, feltwork, and the use of clay—also disputes stereotypes about the strength and dexterity of her body, and is subsumed by a wider critical conceptualization about how bodies should look or feel.

Despite advances in technology—and in addition to the voice of activists and models utilizing social media to tell their own stories—ableism, fetishism, and the strident eroticization of the body as a binary continue to reign in contemporary consciousness. “After ‘the cyborg’ became somewhat tired and tiresome from academic overuse, we started to hear and read about ‘the prosthetic,’” Vivian Sobchack scathingly elaborates in her essay for The Prosthetic Impulse: From A Posthuman Present to a Biocultural Future (2006), “When I put my leg on in the morning … I don’t find it nearly as seductive a matter—or generalized an idea—as do some of my academic colleagues … neither do I feel like Barthes’s ‘reified hero,’ the ‘Jet Man’ — a mythological ‘semi-object’ whose prosthetically enhanced flesh has sacrificially submitted itself to ‘the glamorous singularity of an inhuman condition.’”14

Sobchak’s comments on the objectification of the body returns to the frustration found in Lindauer’s book, who was writing to attempt to liberate Kahlo from a narrative of suffering, ossified within an alluring and endless litany of her emotional and physical (un)health.

As Jorge Alberto Lozoya said, “It is difficult to approach Frida Kahlo without getting caught by the virus of fetishism.” The trite aestheticization of pain as image, as representation without source, undermines the nuanced interplay between material culture and subjectivity, trauma and shelter.

These narratives function as coded mythologies, employing the surrealism which Kahlo always disavowed. “They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams or nightmares,” she famously said—which now means it’s probably engraved on a pocket mirror, or stitched onto an overpriced t-shirt somewhere—“I paint my own reality.”

- Sisters Uncut, #GE2017: Theresa May is No Sister of Ours, 19 April 2017, http://www.sistersuncut.org/2017/04/19/ino-sister-of-ours/

- Margaret A. Lindauer, ‘Fetishizing Frida,’ in Devouring Frida: The Art History and Popular Celebrity of Frida Kahlo, University Press of New England, 1999, p 154

- Miyako Ishiuchi in M Kasahara, ‘Ishiuchi Miyako: Traces of the Future,’ in Mother’s 2000-2005: traces of the future, The Japan Foundation and Tankosha Publishing Co. Ltd, 2005, p 125

- Miryam Sass, ‘Second Skin,’ in Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows, Getty Publications, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2015, p 126

- Miyako Ishiuchi interviewed by K. Griffin in ‘Ishiuchi Miyako: “Waiting to say Hello” to Clothing from Hiroshima,’ in The Vancouver Sun, 25 October 2011

- Olivia Laing, The Lonely City, Canongate Publishing, 2016, p 276

- ibid

- Jessica Beck, ‘Introduction,’ in Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, The Andy Warhol Museum, 2016, p 6

- Sarah M Lowe, ‘Essay,’ in The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait, Abrams, 2006, p 29

- Rachel Dedman, Labour of Love: New Approaches to Palestinian Embroidery, The Palestinian Museum, Ramallah, 2018

- Lowe, op cit

- Sandie Yi, Crip Couture, https://www.cripcouture.org/about.html

- ibid

-

Vivian Sobchack, ‘A Leg To Stand On: Prosthetics, Metaphor, and Materiality,’ in The Prosthetic Impulse: From A Posthuman Present to a Biocultural Future, eds, Marquard Smith and Joanne Morra, MIT Press, 2006, pp 17-41